I know just enough about research to be dangerous. That's mostly a joke, but not entirely. As an undergraduate, graciously allowed to take Ed School graduate courses (thank you, Gerry Lesser!), I learned how to read and interpret research, and some rudimentary study design. But, that was so long ago that we gathered and processed data on punchcards, and our math capabilities were limited because we hadn't yet evolved opposable thumbs. You wouldn't want me writing the questions or moderating the interviews.

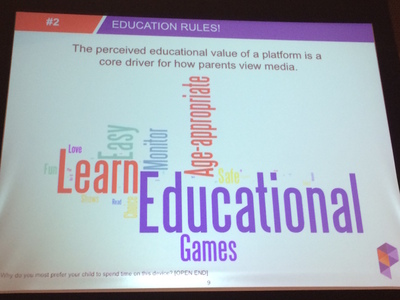

At this week's Sandbox Summit, we released a PlayScience study of parents, platforms and preferences, with just a teaser for another study we've fielded, on the children's VOD market, that will be issued quite soon. Here are the slides we presented.

More than much of the client-based work we do, I've had a chance to be involved in this from start to finish, and it's reminded me that one of the great pleasures and privileges of my job is to listen to our research team as they develop, execute, analyze and report studies. Here are five reasons I love collaborating on research.

It's never finished.

Every study not only provides insights, it poses new questions. As soon as our report was shared, in the hallways at Sandbox and on social media, many other researchers came to us with questions and suggestions for deeper dives into the existing data, follow-up or ongoing tracking studies. Given how quickly the family technology environment is changing, PlayScience could track this study every six months for the foreseeable future and get useful longitudinal insights. Our forthcoming VOD study was conducted just weeks before YouTube Kids was launched. That makes it a unique and valuable snapshot of a moment, and a baseline for change in a shifting field.

It's coding.

With all the attention right now to teaching young people how to code, my feeling is that what we really mean by this is that they should learn how to think logically and analytically, and to review a sequence of steps or events to find and correct flaws.

A good research designer does just the same. At the data gathering stage, that involves identifying what questions need to be asked and in what sequence, establishing a narrative to help those being surveyed to respond with clarity and get meaningful results. When it comes to analysis, there has to be a consistent and logical structure to the presentation. If some findings are among all families and some just among those who fit a particular condition, this has to be clearly delineated and honestly revealing of the information being sought. As when writing code, if there's an inconsistency that affects clarity, it has to be traced back to the source and addressed up and down the line.

It's connective and collaborative.

Studies can mesh to reveal even more. Just shortly after we posted our "platforms and preferences" study, other researchers - both academic and from industry, began commenting on research they'd done or data they held that might pair with ours. For example, Jessica Taylor Piotrowski, a leading academic researcher based in the Netherlands, posted to Facebook of a study she and her Ph.D. student had just finished, with 600 Dutch parents, "to identify what they consider the main 'needs' they (and their children) have when it comes to apps, and what specific 'features' of apps can meet these needs. We are analyzing this based on both demographic characteristics as well as parenting style." This will add multiple dimensions to the PlayScience report, such as an international perspective as well as a drill down into specific content for the devices we explored.

It's additive - one work inspires others.

The research world is a Tetris game where every new study fits into a history, both of findings and methods. A project may begin with a review of past literature on the subject, building a framework from what we already know, the strengths and weaknesses of that knowledge base, what's changed since the previous studies. Children and media research rests on studies done over 50 years, but primarily on television. Today, without abandoning that history, we're asking new questions and forging new methodologies in order to understand the unique new world of digital, interactive, mobile devices and their particular affordances.

It's creative.

As families' lives get more complex, so too do the challenges of understanding them. In recent years, PlayScience has generated all sorts of innovative methods for specific times, places and questions, like getting families to install time-lapse programmed digital cameras on top of their TV sets to capture the who, how, when and where of family viewing. Every new study begins with a brainstorm of best practices for getting the needed information in ways that are accurate, timely, non-intrusive and - especially in the case of research with kids - fun and engaging.

Whether inside PlayScience, in academic settings worldwide, at conferences, or on the Children and Media Professionals group on Facebook, researchers are naturally curious people, ever asking "what if..." questions and proposing "yes and..." studies. They're improvisers, innovators, inquirers and inspirers, and I love the chance to work with them.

A version of this post first appeared in Kidscreen.