This June marks the five-year anniversary of the end of the Great Recession, but champagne toasts would be distastefully premature, as the U.S. economy remains far from fully recovered. The partial recovery that has materialized has been quite uneven, favoring growth of corporate profits and stock prices over employment and wage growth, while wide discrepancies persist in regional economic health.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a March NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll showed 57 percent of surveyed American adults believed the United States was still in a recession (although that is the lowest share of respondents under that impression since early 2008).

The Great Recession officially began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, which determines the start and end dates of U.S. recessions based on a range of economic indicators.

Now, five years after emerging from recession, the best metrics of economic health suggest the economy is only between one-third and half of the way to fully recovered. What are the key features of this continued sluggishness in the economy?

Seven Million Jobs Still Needed

The Great Recession was the most severe economic downturn and longest-persisting recession since the Great Depression. Employment fell by 6.3 percent -- more than twice the decline in the 1981 recession, three times the decline in the 2001 recession, and four times the decline in the 1990 recession.

Early into the recovery, roughly 11 million jobs were needed to restore the unemployment rate to pre-recession levels. Today, that number stands at an improved, but still staggering 7 million jobs needed, according to estimates by both the Economic Policy Institute and the Brookings Institution. Less than 40 percent of the employment shortfall caused by the Great Recession has been closed.

Regrettably, recovery from this severe downturn remains years away. The economy has added 198,000 jobs per month on average over the last year, and just slightly less over the past two years. If this pace of hiring is sustained, it will take nearly another five years to restore pre-recession unemployment rates.

Prime-age Workers Still Underemployed

The most publicly visible indicator of labor market health is the national unemployment rate, which has witnessed a precipitous but misleading drop in recent years. Unemployment averaged 4.6 percent in the year leading up to the Great Recession and then spiked to 10 percent in October 2009. Since then, unemployment has fallen back to 6.3 percent as of May, perhaps wrongly suggesting that roughly two-thirds of the labor market downturn has abated.

But the unemployment rate has been an exceptionally misleading economic indicator in recent years, primarily falling because workers have been dropping out of the labor force, not because a rising share of the population is employed. The Economic Policy Institute estimates that nearly 6 million workers are still "missing" from the labor force because of the lack of jobs. If these workers were considered unemployed but still in the labor force, the unemployment rate would register 9.7 percent.

A more illuminating metric of labor market health is the share of prime-age workers (ages 25-54) who are employed. In the year before the Great Recession, that share averaged 79.9 percent; in May, only 76.4 percent of prime-age workers were employed, and less than one-third of the decline from the Great Recession has been recovered.

Furthermore, even if the 6.3 percent unemployment rate were an accurate assessment of labor market conditions, it still should -- under remotely sane political conditions -- be cause for grave alarm. The highest unemployment rate reached in the aftermath of the 2001 recession was 6.3 percent (which was also cushioned by a substantial loosening of monetary policy).

Aggregate Economic Activity Is Still Depressed

Just as the labor market is operating well below potential, so is the economy in general, by the broadest measures.

Inflation-adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) -- the most comprehensive measure of economic activity--contracted 4.3 percent between late 2007 and mid-2009, even as the key drivers of increased economic output (U.S. productivity and population) continued to rise over this period, as well as during the ensuing, sluggish recovery.

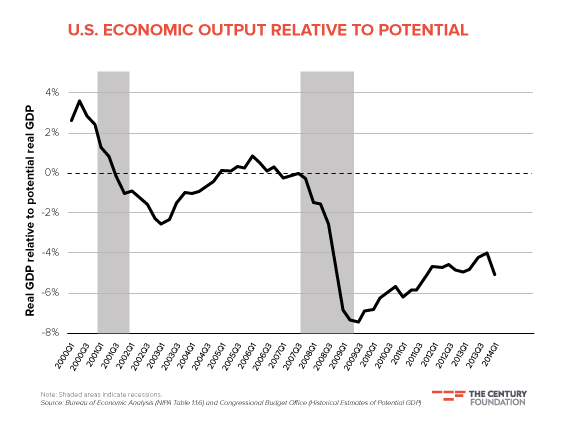

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) frequently issues forecasts of potential GDP, to estimate how the economy is performing relative to what could be produced if the economy were running at full employment and full utilization of other productive resources, such as industrial capacity. By mid-2009, U.S. GDP had fallen 7.4 percent below CBO's measure of potential.

Nearly five years later, the U.S. economy was still running 5.1 percent below potential GDP as of the first quarter of 2014 (exacerbated by a sharp contraction in GDP that quarter), down from averaging 4.5 percent in 2013. This means that less than 40 percent of the shortfall in potential output inflicted by the Great Recession has been recovered.

Slightly more conservative annual estimates issued by the International Monetary Fund show just over 40 percent of this shortfall in U.S. potential GDP having been closed in 2013 and a little over half projected to be closed in 2014.

Why do we have persistent shortfalls in economic activity, well below potential? Since the end of the Great Recession, real GDP growth has averaged 2.1 percent annually. This would be a fine pace of growth if the economy was at full health, but it is an intrinsically problematic "catch-up rate" when we are starting from a deeply depressed economy.

The CBO estimates that potential GDP growth averaged 2.2 percent over 2002-13 (driven by productivity and population growth) and is projected to average 2.1 percent over 2014-24. Essentially, the depressed economy is growing about as fast as the higher level of potential output it needs to catch up with; faster growth is needed for progress back towards economic potential and full employment.

Inflation Pressure Is Conspicuously Missing

If the labor market were approaching full health, and GDP approaching potential output, we would be seeing an uptick in inflation, as increased demand for workers pushed up wages. Instead, we've witnessed a marked deceleration in inflation, to rates well below what Federal Reserve policymakers view as healthy.

The central bank's stated inflation target is two percent annual growth in the price index for personal consumption expenditure. But the preferred measures of both inflation and "core" inflation (which excludes volatile energy and food components) rose only 1.1 percent over the last year, having remained under the 2 percent target, and gradually decelerating, for the past two years.

Citing below-target inflation as a key motivation, the Federal Reserve's most recent policy statement suggested that their long-standing zero interest rate policy will still be maintained for a considerable period of time -- a stark signal that the nation's top macroeconomic policy setters perceive an economy far from healed.

Congress Still Needs to Address the Economic Damage

The current economic malaise partly stems from the severity of the downturn. The housing bubble's implosion and ensuing financial crisis that triggered the Great Recession was a gargantuan shock to the economy, creating so much damage that the Federal Reserve could not singlehandedly restore the economy to full health.

But rather than helping spur growth until the economy was fully recovered, our fiscal policymakers went down a wrongheaded path of fiscal austerity, slowing growth, and adopted a position of political intransigence and apathy, thwarting other policies to heal the economy.

In particular, congressional Republicans have consistently obstructed policies that a majority of economists believe would boost recovery while extracting policy concessions that most economists believe have slowed recovery (notably government spending cuts).

The continued failure of Congress to do something as simple and sensible as renewing emergency unemployment benefits that expired six months ago is just the most recent example of congressional Republicans obstructing a commonsense policy to aid the beleaguered labor market.

Five years after the end of the Great Recession, the economy is far from healthy. A tragic mix of budgetary blunders and congressional inaction deserve the lion's share of the blame for this. It is imperative that Congress reverse course and boost economic activity with greater public investment and safety net spending until output and employment again reach their potential.