Last month a YouTube video about women's periods went viral. It poked fun at the advertisements for feminine care products that feature ecstatically happy women running on beaches in white spandex, twirling in slow motion, dancing, and even bleeding blue blood. It reminded us that there's something disturbing about these messages. The video seemed to understand that images in the average feminine care product commercial suggest that women are polluted, cantankerous, brownie-inhaling trolls that require Stepford menstrual stand-ins. But the video turned out to be yet another one of those ads -- for Kotex -- and we'd been had.

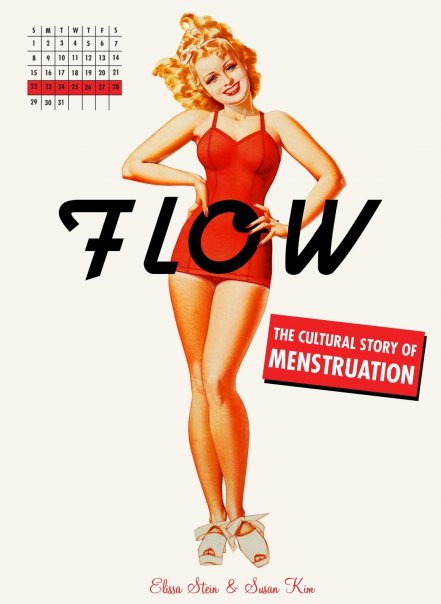

Elissa Stein and Susan Kim -- with seemingly eerie foresight -- recently published Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation, a book that approaches its taboo topic with plenty of irreverent humor and refreshing bluntness. Most importantly, however, the book actually does what the Kotex ads only pretended to -- it debunks myths, urges us to stop listening to such harmful stereotypes, and asks us to consider the realities of our own bodies. One way it helps us tune out the commercial conditioning we have internalized is by analyzing the role that language -- and particularly the reckless argot of advertising -- has played in how we treat the female body.

Stein and Kim demonstrate that, rather than being viewed as the harmless, natural process that it is, the woman's period has been demonized, medicalized, and mediated into an ideological ghetto: "Hidden in a figurative box (scented, of course), stuffed deep inside the great medicine cabinet of American culture: out of sight and unmentioned." One of the authors' most effective and eye-catching modes of tracing how this came to be is through a photo history of period management ads. This record of the brainwashing and bullying of women for profit provides chilling insights into perceptions of femininity.

Stein and Kim draw an intriguing parallel between contemporary ad men and ancient male myth-makers who had the power to create the dogma that defined their people. The authors remind us that, in order to sell their menstrual wares, feminine care ads have employed the "centuries-old message that the process itself is unspeakable and a source of deep shame. While such ads didn't invent self-loathing, they sure as hell capitalized on it... advertisers have profoundly influenced what we know and how we think and feel not just about our periods, but our very bodies."

The book documents a Kotex advertisement that promises the woman who employs its product that she will be "Protected better. Protected longer. And a better woman for it." This begs the question, what standards of femininity include plugging up a lady's flow hole in order to make her a better woman? This kind of advertising language sets in motion a dangerous cycle: Words can reveal beliefs, but they also form and maintain them. As women peruse this period propaganda, we see the female body morph into a reeking vessel of shame that must be sterilized, aromatized, and exorcized in order to be considered attractive again.

But even when calling out the average feminine care ad, Stein and Kim aren't perfect. They engage in negative language when they talk about how the Food and Drug Administration decided "to grow a pair" when it finally regulated harmful douches. By linking male sex organs to bravery, the authors employ the kind of language they critique throughout the book. Rest assured, as Stein and Kim tell us, antidotes are on the way in the form of a crop of websites set on righting these linguistic and ideological wrongs. At a site called Woman Wisdom, for instance, readers can learn all about "the shamanic power of menstruation," and "the eroticism of blood mysteries."

In one of Flow's last sections on fears about menopause and aging, Stein and Kim are particularly astute when they sum up the sentiments of the media-saturated female:

We dread turning into a lumpish, sexless gnome in a pastel sweatsuit, existing for the free cheese samples at the supermarket and owning too many mugs with funny sayings on them. And even if we don't have a maternal bone in our body, we brood endlessly about the last gasp of fertility, the end of our 'usefulness' as women.

That's when it hits us. Advertising companies have been able to control us for centuries for one reason and one reason alone: They've made a killing off women's fears of turning into a Cathy cartoon.

Somebody needs to tell these ad folks that they can't have it both ways. If they want us to believe that our periods render us unsexy and in need of sterilization, they can't also claim that we lose carnal appeal when flow stops coming to town. As Stein and Kim demonstrate with more than a little moxie, it's time to stop the madness.

Cross-posted on Campus Progress