Identity theft in chess is rather common. Sometimes a full chapter is lifted from a book, other times a player claims credit for a single move that wasn't his. Here is one such story.

It was a furious attack launched against me at the 1965 Student Olympiad in the Romanian mountain resort of Sinaia, a perfect onslaught by a local player that even Bobby Fischer would have approved of. For the first 11 moves of the Sicilian Najdorf, I was under fire from the 30-year-old Romanian student Traian Stanciu. By move 12, my black pieces were in crossfire. Suddenly, a funky defense crossed my mind and I realized I was not only safe, but my chances to turn the game around were excellent. For the next 25 years, my discovery over the board was a sleeper. Nobody paid attention to it, nobody played it, nobody wrote about it.

It resurfaced in 1990, after the well-known journalist Leontxo Garcia pointed it out to the Spanish TV-viewers. They were challenging Garry Kasparov in a two-game match that lasted two years. In April 1993, Kasparov described the experience from that match and included my move in his article for the Chess Life magazine. I showed it to Nigel Short in my house during our preparation for the 1993 world championship match against Garry. By now the knowledge about my counterpunching defense was widespread. It was known in Spain, in the United States and to Kasparov's army of coaches and seconds. Soon it was the top suggestion of computer engines and my game with Stanciu was featured in major databases.

Everything was going well for my move 12...d5, but in 1996 it was stolen. In the VSB tournament in Amsterdam, Nigel Short used my discovery to defeat Veselin Topalov and promptly claimed it as his novelty. It fooled the chess world. When Sharyiar Mamedyarov played it in this year's elite Sparkassen tournament in Dortmund, Germany, Chessbase.com presented it as Short's refutation and fantastic novelty. The usually reliable daily Internet newsletter, Chess Today, thought it originated in the game Topalov- Short.

Today, I declare my authorship of the move 12...d5 and reclaim my identity back.

Let's see the game that brought back the memories.

Naiditsch - Mamedyarov

Sicilian Najdorf , Fischer Attack

Sparkassen GM tournament, Dortmund 2010

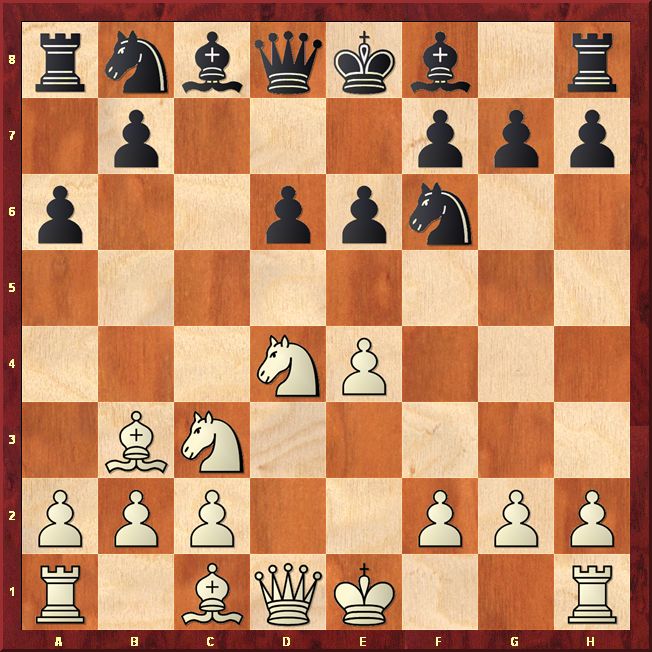

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bc4 (The Fischer Attack the young Bobby played almost exclusively. In 1975, I wrote a full chapter about it in "The Najdorf Variation of the Sicilian Defense," a RHM book I co-authored with the legendary grandmasters Yefim Geller, Svetozar Gligoric and Boris Spassky. It came in handy in 1993 when I was preparing Short for his match against Kasparov. It turned out to be Short's most successful opening in the match.) 6...e6 7.Bb3

7...Nbd7 (The knight goes to the square c5, where it protects the pawn e6 and attacks the pawn on e4. The main line used to be 7...b5 8.0-0 Be7, but Fischer's queen-sortie 9.Qf3!? from his game against Fridrik Olafsson, Buenos Aires 1960, gave Black hard time. GM Evgeny Vasyukov played it against me in the 1966 match Moscow-Prague and after a long deliberation, I invented a queen maneuver 9...Qb6 10.Be3 Qb7 over the board. The game ended: 11.Rfe1 Nbd7 12.Bg5 Ne5 13.Qe2 Bd7 14.a3 Rc8 15.Rad1 Nc4 16.Bxc4 Rxc4 draw agreed. Ever since then, the queen fianchetto became a good weapon for Black.) 8.f4 Nc5 9.0-0?! (A questionable pawn sacrifice that can still give you some headaches. After seeing Kasparov's article in the 1993 April issue of Chess Life, the castling move was dismissed in our preparation with Short. We concentrated on three moves, 9.f5,9.e5 and 9.Qf3, and in the actual match, Short made a good use of all three.) 9...Nfxe4! 10.Nxe4 Nxe4 11.f5 e5 12.Qh5 (Black is now at a crossroads.)

12...d5! (When I played this move against Stanciu at the Student olympiad in Sinaia in 1965, I thought I was winning. What can White do? Certainly moving the knight makes him vulnerable on the diagonal a7-g1. But Kasparov chose a different defense with Black in 1990, protecting the f-pawn with the queen: 12...Qe7 13.Qf3! Nc5 14.Nc6 Qc7 15.Bd5 a5 and here the Spanish TV audience in 1990 chose 16. Be3. When Kasparov repeated the moves in Amsterdam 1996, Veselin Topalov came up with 16.Bg5! Ra6? 17.Nd8! and Kasparov was done, although he resisted and lost in 66 moves.) 13.Re1! (I realized I was in terrible crossfire.) 13...Bc5 (After 13...Qc7 White can sacrifice a piece 14.Bxd5 Nf6 15.Bxf7+!? Qxf7 16.Rxe5+ Be7 17.Qe2 Kf8 18.Bg5 with strong pressure.) 14.Rxe4 Bxd4+ (Black would love to castle, bringing his king to safety. The immediate 14...0-0 prevents 15.Rh4? because of 15...Bxf5!; but White can play 15.Rg4!? Bxd4+ 16.Kh1 e4 17.c3 Bf6 18.Bh6 Kh8 19.Be3 with excellent compensation for the pawn. Postponing 14...Bxd4+ 15.Kh1 0-0, allows 16.Rh4! Bxf5 17.Rxd4 g6 18.Rg4 and White is better as was known to Kasparov and to the Spanish TV-viewers already in 1990.) 15.Kh1 (Stanciu's choice. The game Topalov-Short, Amsterdam 1996, went 15.Be3 0-0 16.Rxd4 exd4 17.Bxd4 and after 17...f6 [17...Re8 seems better] instead of 18.Bc5 and losing in 46 moves, Topalov should have played 18.Qf3! with good compensation for the exchange. The Romanian analytical tandem, Stanciu and Stoica, later recommended another exchange sacrifice 15.Rxd4!? Qb6! 16.c3 exd4 17.Qe2+ Kf8 18.Qe5. It doesn't seem to give White any advantage either.)

15...Qf6!? (Black has more choices playing this way. During my game with Stanciu, I was concerned about my d-pawn and chose 15...Qd7, but after 16.Re1, instead of the faulty 16...0-0?, I should have played 16...Qxf5!, for example 17.Qxf5 Bxf5 18.c3 Ba7 19.Rxe5+ Be6 20.Bxd5 Rd8 21.c4 0-0 and black has no problem to equalize. Kasparov' judgment that White is better after 15...0-0 16.Rh4 Bxf5 17.Rxd4 g6 18.Rg4 was confirmed in the game Maslak - Dvoirys, Sochi 2005: 18...Kh8 19.Qh4 Bxg4 20.Qxg4 f5 21.Qf3 d4 22.Bh6 e4 23.Qg3 Qf6 24.Bg5 Qg7 25.Rd1 Rae8 26.Kg1 e3 27.Bf4 Qf6 28.h4 Re7 29.Bg5 Qe5 30.Qxe5+ Rxe5 31.Bf4 Ree8 32.g3 Kg7 33.Kg2 Rf6 34.Kf3 and Black resigned.) 16.Re1 (It is possible I didn't like the move 15...Qf6 because after 16.Bxd5 Bxf5 [ or16...Qxf5 17.Qe2!] 17.Rxd4 exd4 18.Bg5 Qg6 19.Re1+ Kf8 [19...Be6 20.Bxe6! wins] 20.Qh4 the black king is not out of the woods yet.) 16...Bxf5 17.c3 Ba7 (A new move, but hardly any better than the previously played 17...Bc5. The risky 17...Bf2 18.Rf1 g6 leaves Black with weaknesses and after 19.Bg5 White is better.) 18.Bxd5 0-0 19.Rf1?! (Wasting time and turning the chances in Black's favor. White should have played 19.Bg5! Qd6 20.Rad1 Bg6 21.Qe2 with a slight edge.)

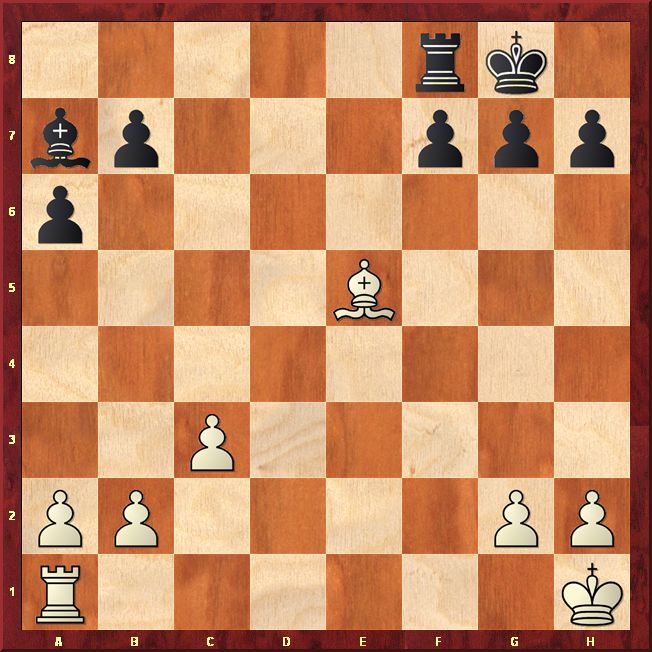

19...Qd6! (Mamedyarov was always great in trading tactical punches. Not only does he escape from the pin, but he forces White to defend.) 20.Rxf5 (20.Bxb7 Bg6! 21.Qd1 Rad8 is in Black's favor.) 20...Qxd5 21.Rxe5 Rae8! (Taking advantage of the weak first rank, Mamedyarov shapes the game to his liking.) 22.Bf4 (22.Rxd5? allows 22...Re1 mate.) 22...Rxe5 23.Qxe5 Qxe5 24.Bxe5

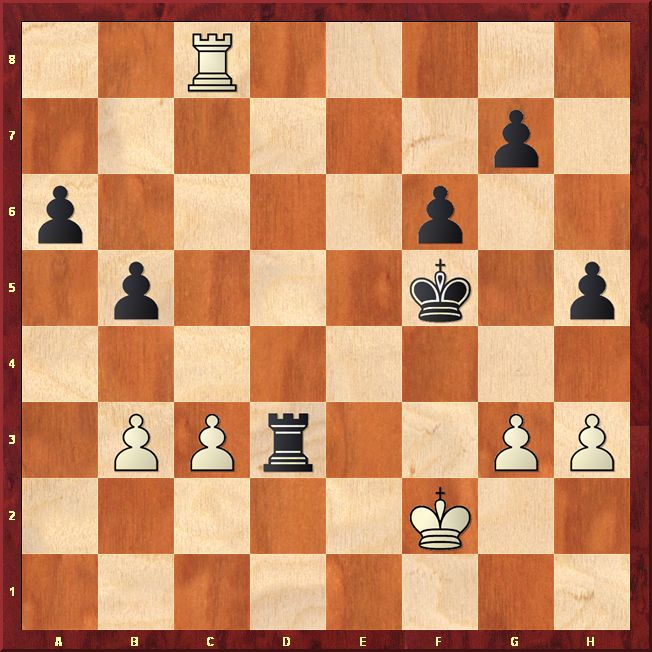

24...f6! (An important move, chasing the bishop away from its central position. White is worse. His king is cut off and the black rook may soon fly down.) 25.Bc7 (The rook endgame is hopeless after 25.Bd4 Bxd4 26.cxd4 Rc8 27.Kg1 Rc2. The black rook dominates and the king can take care of the d-pawn.) 25...Re8 26.Rd1 (After 26.h3 Re2 27.Rb1 Kf7 the active black rook is a decisive factor.) 26...Re2 27.b3 (Defending passively does not help. After 27.Rb1 b5 28.h3 Kf7 29.Kh2 Ke6 30.Kg3 Kf5 the white king can't come closer since 31.Kf3 Re3+ 32.Kf2 Re7+ drops a piece.) 27...Rxa2 28.g3 Ra3 29.Rb1 h5 [29...Bc5 30.b4 Be7 31.c4 Kf7-+] 30.Bd6 Ra2 31.Re1 Rd2 32.Bb8 (Seeking a respite in the worse rook endgame.) 32...Bxb8 33.Re8+ Kf7 34.Rxb8 Rd7 35.Kg2 Ke6 36.Kf3 Kf5!? (36...Rd3+ 37.Ke4 Rxc3 38.Rxb7 is not as clear.) 37.h3 Rd3+ 38.Kf2? (Protecting the h-pawn with 38.Kg2 was better, but not adequate.) 38...b5 39.Rc8

39...h4! (Securing two connected passed pawns wins the game.) 40.gxh4 Rxh3 41.Rc7 Kg6 42.Rc6 b4 43.cxb4 Rxh4! 44.Rb6 Re4 45.Kf3 Kf5 46.Rb7 (After 46.b5 Rb4! decides.) 46...g5 47.b5 a5 (After 48...g4+ 49.Kg3 Rb4 50.Rxa5 Rxb3+ 51.Kg2 Kg5 wins.) White resigned.

Note that in the replay windows below you can click on the notation to follow the game.

The traditional Sparkasse grandmaster tournament in Dortmund was a six-player double-round affair. It finished Sunday with Ruslan Ponomariov's victory. The Ukrainian grandmaster scored 6,5 points in 10 games, a full point ahead of Le Quang Liem. The Vietnamese grandmaster was a big surprise of the event and the only one who defeated the winner. He qualified for Dortmnud by winning the strong Aeroflot Open in Moscow in February. GM Alexander Khalifman, who coached him, predicted a bright future for him. GM Vladimir Kramnik of Russia and GM Shakhriyar Mamedyarov of Azerbaijan shared third place with 5 points. Hungary's Peter Leko and Germany's Arkadij Naiditsch ended last, both with 4 points.

Something must be going on in Vietnam. Another grandmaster, Nguyen Ngoc Truong Son, shared first place with Maxime Vachier-Lagrave of France and the American-Italian GM Fabiano Caruana at the Young Grandmaster tournament in Biel, Switzerland. They all scored 5,5 points in 9 games, but Caruana won the playoff today.