As growing numbers of students at for-profit colleges have defaulted on their debts in recent years, bringing government scrutiny and the threat of financial penalties, some institutions have unleashed a novel strategy aimed at improving their numbers: They have systematically encouraged students to stay current on their debts just past the point at which the government measures default rates.

Companies have established call centers that locate former students at imminent risk of default and contact them dozens of times to urge them to seek official extensions on their debts, according to plans outlined in internal documents obtained by the Senate education committee and reviewed by The Huffington Post.

The goal: reduce the number of students who fall behind on their payments within two years of leaving the institution, the time frame the government uses to measure the student loan default rate. By reducing that number, for-profit colleges have been able to avoid financial sanctions threatening their access to federal financial aid dollars -- the source of more than three-quarters of revenue for publicly traded college corporations.

But critics argue that such tactics only delay the risk of default, leaving former students shouldering more debt in the long run.

At Corinthian Colleges Inc., which owns a network of more than 100 schools across the country, employees went door-to-door and gave out McDonald's gift certificates to entice delinquent former students to inquire about "postponing payments." At Career Education Corp., an internal handbook detailed a policy where employees called delinquent borrowers an average of 46 times to prevent defaults, and instructed them to track down past students through family members, friends or employers. Other schools, including Kaplan University, hired private investigators to find former students and encourage them to sign forms delaying loans.

The aggressive push, detailed in the emails and internal company documents collected by Senate staffers over the past two years, has allowed schools to keep student loan defaults temporarily in check. But a group of senators is now asking the Department of Education to investigate whether the schools' efforts are an attempt to manipulate government regulations in favor of the colleges, not students.

"We are very concerned that the tactics employed by some colleges to evade default-rate laws and sanctions are harmful to students and taxpayers," read the letter sent to the Department of Education by eight Democratic senators earlier this month, including Sens. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.) and Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), a chief critic of for-profit colleges. "We urge you to immediately investigate these reported practices and take swift action to stop their use and abuse."

A spokesman for the Department of Education, Daren Briscoe, said the agency was still reviewing the details, but added: "We would have serious concerns about any evidence of institutions trying to circumvent the laws and regulations governing the calculation of the [default] rates."

Kent Jenkins, a spokesman for Corinthian Colleges, acknowledged that the company has invested significant resources in bringing down default rates, but he said those efforts have been paired with an increased focus on teaching students how to better manage their debts.

"Did we set out to make sure that we were absolutely in compliance? Yeah, because we were going to comply," Jenkins said. "But we also did it in a way to make sure we help our students in the long run, and also to make sure that taxpayers are benefited. It is an honest, good-faith effort to attack the whole problem."

Career Education Corp. spokesman Mark Spencer wrote in an e-mail that the company's schools often serve non-traditional students who are single parents and have other jobs. He said the company goes "above and beyond" to "discourage students from over-borrowing, to provide financial literacy education and to help our students meet their student loan repayment obligations."

Mark Brenner, a spokesman for The Apollo Group, which owns the nation's largest for-profit college, the University of Phoenix, said the company has worked with its contractors to get as many students as possible repaying their loans, as opposed to delaying them. He said the company has incentives built into contracts to reward repayment.

"It is 100 percent our belief that the best approach, if possible, is to get that student into active repayment," Brenner said. "It's better for the student and it's better for the taxpayer."

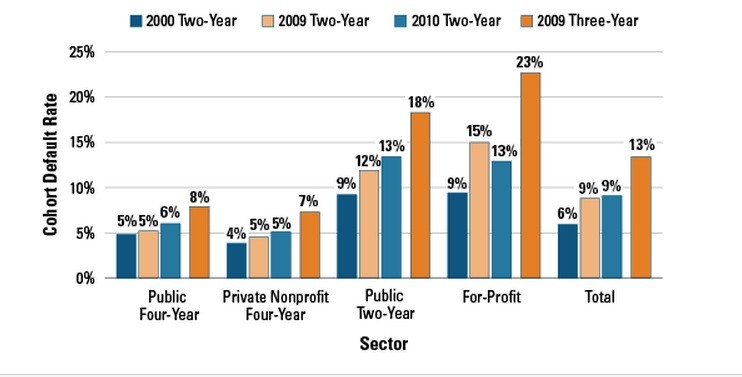

For-profit colleges, which range from trade schools such as ITT Technical Institute to large online institutions like Kaplan University, have historically had significant problems with student loan defaults. Students in the sector consistently default on loans at nearly twice the rate of those attending public or private non-profit schools -- prompting stricter government oversight in recent years.

Graphic courtesy of The College Board

The for-profit higher education business model is also inextricably tied to federal government aid. Student loan default rates are one of the few federal standards that govern eligibility for federal government loan and Pell grant dollars. If too many students consistently default on loans within a two-year timeframe after leaving college, a school could be cut off from receiving future aid.

The call centers and "default management" teams at many for-profit colleges are part of an attempt to reduce a school's default rate by either convincing students to pay part of the loan or officially delay payments and avoid default. (A federal student loan is considered in default when a borrower has not made a required payment for 360 days.)

Employees or contractors hired by some colleges often try to convince borrowers to defer payments (which usually freezes interest rates), or go into forbearance -- a process that delays a default but can make the loan 20 percent more expensive because interest continues to accrue.

Student aid experts have argued that forbearance is often the easiest option, but also the most harmful to borrowers.

"Putting students willy-nilly into forbearance when it's not in their interest just increases the likelihood of default because the balance is increasing," said Pauline Abernathy, a vice president at the Institute for College Access & Success, in Senate testimony in June 2011.

Documents collected by Senate staffers from several large for-profit colleges show that more than three-quarters of defaults are avoided by students delaying the loans instead of paying them.

Critics say the efforts are aimed primarily at pushing students outside of the default window measured by the federal government -- a process akin to banks keeping bad loans off the books. Senators calling for the investigation questioned whether the federal government and taxpayers are getting an accurate depiction of student loan defaults.

"Aggressive default management undermines the validity of the default rate by masking the true number of students who end up defaulting," concluded an extensive report released earlier this year by Sen. Harkin's staff.

Currently, the Department of Education calculates default rates by looking at how many students default in a two-year period after entering student loan repayment. Beginning in 2014, the government will switch to a three-year window.

Schools lose eligibility for federal funds if they have three consecutive years of default rates exceeding 25 percent (the threshold will be 30 percent under the new three-year default window).

Federal data shows that student loan defaults at for-profit colleges jump significantly after the two-year window. For example, 15 percent of for-profit college students who began repaying loans in 2009 defaulted within two years. That number jumped to nearly 23 percent within three years, according to the data.

Statements and e-mails obtained as part of the Senate report showed that for-profit college executives were aware of the flaws in the system.

Jeff Arthur, a vice president at ECPI, a chain of for-profit colleges based in Virginia, told an industry leadership conference in 2008: "With the proper effort, it really isn't that hard to keep your default rate low!"

"[Default rates] are intended to measure the quality of an institution and whether it is worthy of taxpayer investment in students attending there. LOL," Arthur continued, according to the transcript. "In reality, they can tell us that a college is doing a good job of following up to make sure their former students follow a few simple steps to stay out of default … just for a while, then we don't care."

Arthur and representatives from ECPI did not respond to requests seeking comment this week.

Additional documents obtained by Senate staffers reveal a sophisticated, well-organized approach to managing defaults by many for-profit college corporations.

At least 11 major for-profit college corporations, including Corinthian, DeVry and the Apollo Group, which owns the University of Phoenix, contract with General Revenue Corp., which operates call centers aimed at contacting students and keeping them out of default, according to documents in the report. GRC, which did not return requests for comment, is a subsidiary of Sallie Mae.

Most of the companies provide GRC bonuses, some as high as $120, based on how many potential defaults were remedied.

Brenner, the Apollo Group spokesman, said the company actively tracks how many defaults are prevented through repayment, and how many through forbearance. "We reward the behaviors of active repayment, and we eliminate contractors that are overweight in forbearance," he said.

Brenner added that the Department of Education could do a better job of incentivizing its contracted loan servicers to reward repayment, as opposed to forbearance.

Other internal company documents showed an aggressive emphasis on tracking down former students.

In 2008, Kaplan finalized a contract to pay private investigators $575 for every "successful resolution" to a potential default. The document instructed investigators to get a signed forbearance form from the student.

A spokesman for Kaplan said the company was unable to provide comment during the holiday week. A Kaplan spokeswoman said last year that the company hired an outside contractor to find students whose contact information was out of date, and who could be at risk of default without knowing.

Corinthian Colleges has openly touted its aggressive default management plans in conference calls with investors over the past two years, explaining how the company reduced its two-year default rate from 21.6 percent to 6.7 percent. Yet Corinthian's academic programs ranked among the worst in the nation for student debt management, based on Department of Education statistics released in June. The data looked at how many students were able to repay at least a portion of their loans, and whether students had an excessive debt burden compared to their income.

Jack Massimino, chief executive of Corinthian Colleges, acknowledged in a May 2011 investor conference call that most students were delaying payments as opposed to repaying their loans. "Our repayment rate has not moved a whole heck of a lot from where it was prior to this effort," he said.

Jenkins, the Corinthian spokesman, said the short-term efforts at lowering default rates have been scaled down. He said the long-term effort at encouraging repayment will take time to produce results, but added that "it's incorrect and unfortunate that politically motivated critics have chosen to mischaracterize these initiatives."

The senators calling for a review argue such tactics aren't in the interest of taxpayers. The letter calls for the Department of Education to immediately determine a way to identify when schools are improperly averting defaults, and to clarify "what default aversion policies are appropriate and what policies essentially constitute a default manipulation."