Mr. Santo's belly was growing. It had been for months, as his liver hardened and fluid seeped into the void between his bowels and his abdominal wall. A spider web of plump veins stretched across the thinned skin of his former waistline, further evidence of the fluid distortions that plagued his small frame.

He had come to the United States decades earlier, thanks to the Cuban Adjustment Act. As his doctor in the hospital, what happened between then and now is mostly elusive to me. I know he never learned English. I know he didn't renew his Medicaid and misplaced his permanent residence card. Other than the social security number he had memorized, he was anonymous.

I also know he was in and out of hospitals, undergoing large-volume paracenteses every few weeks. It is a straightforward procedure: a needle is placed in the abdomen, and extra fluid, called ascites, is drained into large glass jugs.

Without health insurance, Mr. Santo would continue to volley from the streets to the hallways of our hospital as his abdomen grew and shrank with increasing frequency.

Paracenteses -- or just "paras," as we call them -- are not the preferred maintenance therapy for decompensated liver failure. Furosemide and spironolactone, when given in the correct ratio, mobilize fluid from the abdomen and process it into urine. Both medications can be filled for $4 at Walmart and mailed directly to our patients' homes.

But Mr. Santo didn't have a home. He didn't have a phone, and he didn't have any visitors for the six days when he was my patient. He had soiled his trousers en route to the hospital, so he didn't have any pants, either.

I could find shelters, and I could buy pants. Yet without health insurance, Mr. Santo would continue to volley from the streets to the hallways of our hospital as his abdomen grew and shrank with increasing frequency.

Thousands of uninsured patients are treated in our hospital system each year. At an average cost to the hospital of $2,306 per night, according to Kaiser's State Health Facts, this adds to millions of dollars of unreimbursed services. Many hospitals have found a solution to this: help uninsured patients apply for insurance.

There are standard forms, delivered to patients' rooms by social workers. For those who are illiterate, the form can be filled out by the social worker. For those who don't speak English, the questions can be reviewed over a translator phone. But for those who don't have identification, the form remains incomplete.

In healthier days, Mr. Santo had visited United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to request an ID card. He had arrived unannounced, unable to use the scheduling system without a phone or internet access. As fellow visitors passed under the scanner waiving printed bar codes with appointment information, the middle-aged Cuban immigrant was escorted to the exit; it was no longer possible to make an appointment in person.

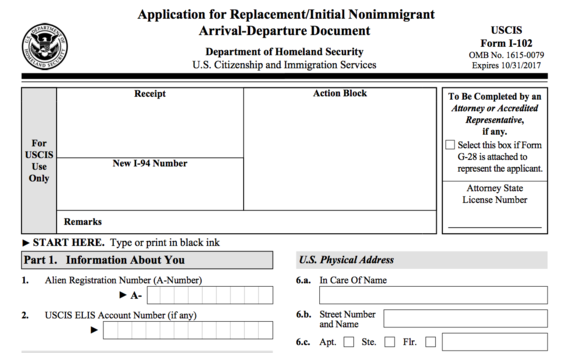

Along with the social worker, I sat by Mr. Santo's hospital bed and called USCIS. Mr. Santo would have to fill out Form I-102, a voice explained. He would check box 1a in section 2 to show that he was requesting a replacement of Form I-94.

Yet Mr. Santo wouldn't get to section 2, because he didn't know his Alien Registration Number for section 1. Alien Registration Numbers, I learned, were private personal information and could not be given by phone. Mr. Santo would have to go to USCIS himself.

An Alien Registration Number is needed to complete USCIS form I-102.

I looked at my patient, who struggled to walk three feet to the bathroom, holding onto the garbage can and the sink to reach the toilet without sliding to the floor. Liver failure had destroyed his autonomic nervous system. When I stood up, the veins in my legs contracted and pushed blood upwards toward my head. When Mr. Santo stood, his veins hoarded blood and remained idle as perfusion to his brain waned. The result? Chronic, debilitating dizziness.

I explained the situation, repeatedly and with increasing rapidity until the man on the phone broke with his script and yelled, "Are you arguing with me?"

I had been defeated.

So we did what we could. I purchased two pairs of pants, one with an elastic waist to accommodate Mr. Santo's dynamic belly. We made an appointment at USCIS, knowing that Mr. Santo would never recover enough strength to get there. We wrote "Form I-102" on his discharge document, even though he would not be able to complete it. And we wished him well, although we knew he'd falter.

I looked at my patient, who struggled to walk three feet to the bathroom, holding onto the garbage can and the sink to reach the toilet without sliding to the floor.

Doctors don't typically see their patients' hospital bills, but Mr. Santo's six-day stay likely cost our hospital over $12,000. As a monthly stint, this adds to over $100,000 per year.

Studies suggest that a combination of oral medications, along with a low-salt diet, is sufficient for ascites management in 90% of patients. A year's supply of these medications costs $80 at Walmart, but they must be monitored at outpatient care appointments, which are nearly impossible to access without health insurance. For Mr. Santo, this means spending $100,000 for a condition that could be managed for less than $3,000.

All because Mr. Santo is too sick to apply for health insurance.

Mr. Santo's name has been changed.

Sara Manning Peskin is the Chief Blogger at Borderwise.co and a medical resident at the University of Pennsylvania.