Barney Frank was the smartest, funniest, and one of the most effective members of Congress. In his new book, Frank: A Life in Politics from the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage, Frank reveals how he decided to come out of the closet as a gay man, the impact that decision had on his political career, and his subsequent efforts to advance LGBT rights along with other progressive causes, including his influence on Bill Clinton, who despite his advocacy of the harsh "don't ask, don't tell" policy, also showed his support for gay rights in a number of ways.

The book describes Frank's political career, his personal life, and the sometimes awkward connections between the two. Although he was the second member of Congress to come out of the closet, he did not do so on the terms he would have liked. Nevertheless, he was so well-respected among journalists and fellow Congressman that his "outing," although a big news story at the time, did not do much harm to his subsequent political career except in one way. It meant that he would no longer be considered a candidate to be Speaker of the House, which is unfortunate, because he would have been an incredible Speaker.

Right before he came out, Barney went to House Speaker Tip O'Neill, a fellow Massachusetts Democrat, to warn him. In his book, Barney describes his delight when O'Neill immediately expressed support for Frank, saying that he had hoped that Barney would some day become the first Jewish Speaker. O'Neill wanted to help Barney minimize the potential damage, so he told his press secretary (and now an MSNBC talk show host), Chris Matthews: "Chris," he said, "we might have an issue to deal with. I think Barney Frank is going to come out of the room."

Voters in Barney's Congressional district -- which included liberal areas like suburban Brookline and Newton but also more moderate areas like Fall River -- continued to return him to Congress. (He served from 1981 until 2013). After he came out of the closet, Barney broke ground in several ways, including insistence that his then partner, Herb Moses, be invited to all events at which the spouses of other Congressmembers were invited. In 2012, Barney married Jim Ready, making him the first Congressperson to be married to someone of the same sex.

Barney could not avoid being the target of Congressional homophobes. The most disgusting example occurred in 1995, when Cong. Dick Armey of Texas, then the House majority leader, during an interview with a group of radio broadcasters, referred to Barney as "Barney Fag." Armey later claimed that he had simply mispronounced Barney's last name, but nobody believed him. (He later apologized to Barney for his remark, but Armey's subsequent career as a Tea Party spokesperson suggests that he remains an outrageous opponent of LBGT rights).

Barney also reveals some of the surprising support he received from some folks who did so out of basic human decency. One of them was David Locke, a conservative Republican state senator from an area within Barney's Congressional district, who approached Barney and asked him march alongside him at a Memorial Day parade soon after Barney had gone public about being gay. Frank also describes the support he received from conservative Senator Alan Simpson of Wyoming, who supported Frank's word to remove an anti-gay immigration rule and who told Barney that he admired his courage in coming out. Barney also has kind words to say about my former boss, Boston Mayor Ray Flynn, who publicly praised Barney for his support for many liberal causes at a time when some politicians were distancing themselves from the newly out-of-the-closet politician.

Barney's book describes some of the ways he helped advance the cause of gay rights. Despite Clinton's support for the "Don't Ask/Don't Tell" policy in the military, Frank reveals that Clinton was pretty good on LGBT issues in other ways. Clinton hired a number of gay staff members as well as the first openly gay or lesbian presidential appointee -- Roberta Achtenberg, who became assistant secretary of HUD. In 1995, Clinton issued an executive order revoking the ban on security clearances. At Frank's urging, Clinton's Attorney General Janet Reno added people who'd been persecuted for their sexual orientation or gender identity to the list of those who were eligible for refugee status. Clinton also the director of the Office of Personnel Management to send a letter to every federal agency reminding them that they could not discrimination against hiring people on the basis of sexual orientation. One of the most fascinating parts of Frank's book is his revelation -- kept secret until now -- of how he persuaded Clinton not to appoint Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia to become Secretary of State because of his persistent track record of homophobia.

In his book, Barney explains what came to be known as the "Frank rule." Barney knew that quite a few members of Congress, including many Republicans, were gay, but he did not think it was appropriate to "out" them. But he also believed, as he explains in his book, that "the right to privacy does not include the right to hypocrisy." He believed it was appropriate to "out" gay Congressmembers if they used their influence to oppose gay rights, and his book describes a number of instances in which he was on the verge of doing so, but he never carried out his threat.

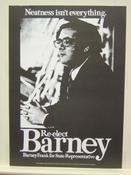

Frank grew up in Bayonne, New Jersey and moved to Boston to attend Harvard and later Harvard Law School. After serving as a top aide to Boston Mayor Kevin White, he ran for the Massachusetts legislature in 1972 from a liberal district in Boston. One of his re-election campaign posters showed a photo of the then-overweight and disheveled Frank under the heading "Neatness Isn't Everything".

When I was teaching at Tufts University and working as a housing activist in Boston in the late 1970s, I got to know Barney, who, as a state legislator, was an effective ally of the housing/tenants movement. When Barney first ran for Congress in 1980, I invited him to speak at Tufts. Even though the campus (in Medford, MA, a Boston suburb) was not in his district, I figured his talk might inspire some students to volunteer for his campaign. But that night, as Barney arrived at the auditorium at Tufts, rather than thank me, he gruffly said, "What the hell am I doing here?" He nevertheless gave an inspiring talk. The next day he called me to apologize for his comment, explaining that he'd had a rough day and was tired and not feeling well that evening, and also said that he was grateful to me for the Tufts students who had signed up to help his campaign.

When I went to work for Boston Mayor Ray Flynn in 1984 (through 1992), I continued to rely on Barney (along with Cong. Joe Kennedy, who was also a member of the House housing/banking committee and also a real progressive) for help on housing issues. At the time, I didn't know Barney was gay, but when he came out in 1987, I wrote him a note expressing my support, and he wrote back a wonderful thank-you note that also mentioned a housing issue he was working on to help protect government-subsidized housing in Boston and other cities, which I had talked with him about several times. He never got the credit he deserved for championing this cause on behalf of low-income tenants.

Barney always spoke very rapidly and with a thick New Jersey accent that made him sound a bit like the cartoon character Elmer Fudd. For most politicians, this speaking style -- which to some sounded like a speech impediment -- would have been a handicap. But Barney was so funny, so quick, and so brilliant that it never posed a problem. It simply meant that to understand him, you had to listen carefully.

Barney used his position in Congress, and his willingness to appear frequently on TV shows and be quoted in the media (reporters loved him because he was so quotable), to advance LGBT rights. But he continued to fight for other progressive causes. One of my favorite of Barney's quips was his statement that right-wing anti-abortion activists, who also typically oppose the government safety net for the poor, "believe that life begins at conception and ends at birth."

During the 1980s, all the major players in greater Boston -- business, labor, contractors, politicians, transportation experts -- supported a huge megaproject to dismantle the elevated I-93 highway that cut through the heart of Boston (officially called the Central Artery) and replace it with several underground tunnels in order to reduce traffic congestion and create a huge park in the middle of the city. The project, often called the "Big Dig," was delayed for many years (construction began in 1991 and wasn't completed until 2007) and wound up costing over $15 billion, more than double the original estimate. Even before construction began, Barney warned that the project could wind up being a boondoggle. He joked: "Wouldn't it be cheaper to raise the city than depress the artery?"

Barney's book is filled with wonderful and insightful examples of legislative maneuvering and political intrigue. His last major battle in Congress was his effort to pass tough regulations on the banking industry, which ultimately led to the Dodd-Frank bill. As Elizabeth Warren describes in her autobiography, A Fighting Chance, Barney was a brilliant legislative strategist. Whenever there were meetings about that bill with other members of Congress, bank lobbyists, and progressive activists, Barney was always the smartest person in the room and always savvy about which compromises to make in order to advance the cause, even if those compromises were not what he (and the reformers) wanted. Dodd-Frank was hardly a perfect bill but it did include some important progressive parts, including creating a consumer financial protection agency that Elizabeth Warren, along with Barney, had championed.

Barney wasn't the most progressive member of Congress, but he generally got close to 100% ratings from unions, environmental groups, women's rights organizations, gun control advocates, and other groups on the left. Like Henry Waxman, who also recently retired from Congress, Barney was a principled liberal who knew how to cut a deal that led to much-needed reforms. The process was rarely pretty, or the way it is supposed to work in textbooks, but Barney has a master at it. He could be caustic and even nasty with people sometimes, but these were characteristics most folks were willing to overlook because he was so damn funny and, more important, so damn effective.

I'm grateful for Barney Frank's great work in Congress over many years. His new book is worth reading as both the story of a public figure who has lived a full and fascinating life as well as a primer about American politics from an insider who knew how to make the system work and who became a voice for people without much political clout.

Peter Dreier is the E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His books include The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame and Place Matters: Metropolitics for the 21st Century.