Kevin Wilkins remembers the summer day long ago when he stared down a member of The Valley, a notorious gang that inhabited the streets of North Philadelphia in the '60s and '70s.

He was around 16 at the time. The gang tested him and his peers from his North Philly neighborhood by beating them. It was a way to see if they were truly tough enough for the life ahead. Wilkins remembered his beating not being too bad.

With shadows of his previous life written into his body -- a tattoo of a panther on his right arm, a lion on his left -- the former gang member does not wish to reveal his true name.

I first met Wilkins a few years ago at the Honickman Learning Center and Comcast Technology Labs, an extension of the nonprofit Project HOME. Wilkins was a frequent visitor, stopping by to collect fliers about upcoming programs.

North Philadelphia, where Wilkins and I both live, has gone through a lot of changes over the years, Wilkins says. A lot of the respect and value in life has been lost.

"You really didn't have a choice back then," Wilkins told me when we started our conversation from his home gym. "I was raised by great parents who showed me nothing but love, but I went astray."

After Saint Elizabeth's Elementary School, Wilkins went to Roman Catholic High School for Boys, where he maintained good grades. He says he doesn't think he was a troubled kid; he was just easily influenced.

Easily influenced -- like some of the youth in my community today. They're not necessarily "bad," but misguided with no one to lead them.

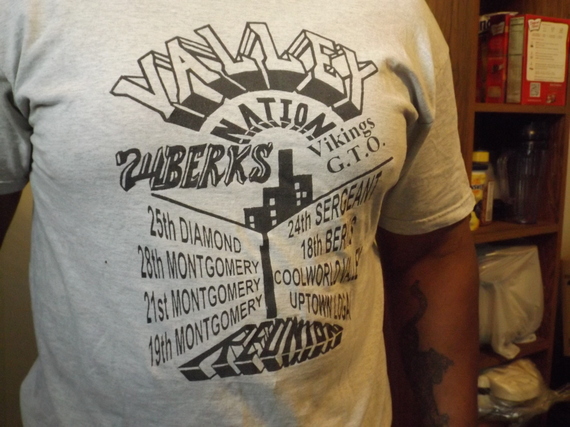

Wilkins was put in charge of certain drug corners. Back then, the Valley occupied known areas in North Philadelphia, such as 25th and Diamond, 18th and Berks, and 19th and Montgomery. Wilkins mentioned that any "outsiders" were not really allowed into those neighborhoods without the Valley's consent.

"If someone was selling drugs across town at some corner, then that was theirs. If I was selling across another part on a corner, then that was mine. We never crossed each other's territory," Wilkins said.

Soon Wilkins became the new dealer in charge. He hired thieves and killers to sell crack, cocaine and other drugs. He admits that he was poisoning people, but at that time he really didn't care.

Wilkins says he hid a lot of what he was doing from his parents, though there were members of the community that knew about his activities on the corners.

"I know the money was dirty and illegal, and it was something I should not have done," Wilkins said, "but the money that I was making I wasn't just using on myself but also the community. I remember this guy who didn't have any money to buy Christmas gifts for his family, so I gave it to him. Drug dealing was fast money."

It's not too hard to understand how Wilkins felt all those years ago. Times are still hard for young African-American men. Many will forgo the straight and narrow just to have what they think they desire. And the seduction of fast cash and fast rides can often sway a person's judgment about the harm he may be inflicting on others.

In addition to selling drugs, Wilkins' dealers also protected many neighborhood businesses and community members under his orders. As Wilkins saw it, doing this helped keep crime down.

To Wilkins, there was a sense of honor among men of his generation. There wasn't a lot of killing then, he said. He won most of his fights with his own two fists, though he says he did carry two guns.

"It was rough during the gang war days," Wilkins says. "But the difference back then was that kids could play outside and senior citizens could easily go about their business. If anything were to happen to a senior citizen or child, we'd find the person and beat him down."

As revered as he was in his community, Wilkins' time soon came to an end. He found himself one day caught up in a fight, and when police arrived, they arrested him on the spot.

Wilkins began serving a 10-year sentence at Holmesburg Prison soon after, being transferred to other prisons along the way such as Camp Hill and Graterford, in order to finish up his term.

"I got into a lot of fights, yes indeed," Wilkins said, half smiling. "I liked to fight. I can still, but I'm not into that anymore."

When I caught up with Wilkins most recently to finish our conversation, he looked like he could still take on anyone. He moved slowly as he showed me around his home, but his gym training had been paying off.

While he was incarcerated, many changes came to North Philadelphia. The Valley and other neighboring gangs started to disband thanks in part to the work of North Philadelphia Mothers Concerned leader Jean Hobson.

The Imani Pledge, a formal promise to avoid violence and achieve greatness, was also instrumental in ending the gang wars. The pledge was spearheaded by Queen Mother Falaka Fattah, mother of U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah and founder of the House of Umoja, an organization that urges an end to gang violence locally and nationally.

On the day of his release back in 1999, Wilkins felt pure euphoria. He checked himself immediately into a halfway house. A month and a half later, he found himself a job with the city of Philadelphia operating street sweepers.

Wilkins is now 55 and considers himself to be reformed as he spends his time helping the North Philly community where he grew up, this time in a more positive way. He tries to talk sense into the next generation of gang members, some of whom are familiar with his past.

Some of the would-be gangsters, actually show him their resumes and the addresses of places they have applied for jobs, Wilkins says.

"Some of them have guns," he said. "But I preach to them like they're my own kids. What I tell them is that I'm not better than they are, and that they're killing one another. It's black-on-black crime."

This story originally appeared on Newsworks.org