Climate change is not primarily an environmental issue.

It's taken me a decade of working on energy and development in 20 countries to realize this. Yes, over half of Earth's species are in danger of extinction from our current pace of climate disruption. But what makes the imperative to immediately act on climate most compelling is what a warmer world means for people, particularly people living in poverty and people of color. To live the dream that we are all created equal, and ensure #BlackLivesMatter as much as any others, we need to place solving climate at the forefront of our minds.

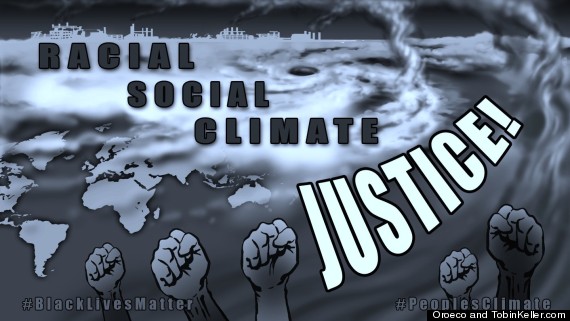

Climate change is the greatest racial and social justice issue of our time.

That's not an opinion, that's what the numbers tell us based on the best available science from thousands of the world's top researchers. It can seem counterintuitive, but global warming is already contributing to extreme weather of all varieties: extended droughts, more intense flooding, record heat waves, historic blizzards and deadly hurricanes. Many scientists have documented how these extremes are already decreasing food production and disrupting water supplies, with much more expected to come. Add in sea level rise, expanded disease ranges, declining fisheries from acidifying oceans, and our propensity for violence linked to warmer temperatures and limited resources, and we have a recipe for humanitarian disaster beyond anything our civilization has known.

The billions of people most at risk from climate chaos are those with the least resources to adapt, who almost invariably are people of color. The Global Humanitarian Forum estimates that climate change is already causing over 300,000 deaths per year, with 99 percent of these deaths linked to poverty in the developing world. A separate DARA report commissioned by 20 governments estimates that climate and other pollution from fossil fuel use will cause over 100 million deaths by 2030; that's more than WWI and WWII, combined. Nearly all these deaths will likely also be poor people of color, and billions more will survive to be trapped in deeper cycles of poverty. This "climate gap" of unequal impacts linked to race and poverty exists in America as well, displayed vividly in the racial disparity in Hurricane Katrina's death and destruction, and connected to thousands of climate-migrants fleeing drought, disease and violence.

Interlinkages between climate, race, inequity and violence can be complex, and this complexity often leads to misunderstanding and underreporting. I was recently invited by the State Department to keynote a conference on climate in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, a city that's been ranked the "murder capital of the world" due to extraordinary gang violence. The biggest surprise from my experience was how my Honduran colleagues linked this pervasive violence to climate. Climate-related explanations started with infrastructure destruction from Hurricane Mitch and continued to a coffee disease that's killed much of the country's primary export crop along with over 500,000 jobs, followed by record drought that's devastated subsistence corn and bean crops, placing more than 100,000 families on emergency food aid. These climate-induced waves of unemployment and desperation increase the likelihood that those affected will join gangs for income and protection, which in turn feeds the cycles of poverty and violence that have caused thousands of Honduran children to migrate to the U.S.

The moral imperative to address the inequities of climate is increasingly being recognized by a wide range of leaders. This week a group of Catholic bishops cited climate poverty as a reason to end all fossil fuel use and transition to 100 percent renewable energy as quickly as possible. The U.S. military has also weighed in, calling climate an "immediate threat" to global security due to food shortages, extreme weather and resource constraints that exacerbate poverty and enhance the likelihood for human conflict and war. Climate fingerprints have already been traced to record drought and civil war in Syria, Somalia and Sudan.

Yet, as compelling as the science is from all sides, we still struggle to tell stories that bring forward the fierce urgency of climate injustice. There will never be a smoking gun or viral video linking a smoke stack or tailpipe to a body on the ground. But we can change how we talk about climate to highlight people over planet, and recognize that the tendrils of climate disruption can find common ground with nearly every social justice issue, whether it be through race, poverty, health or how we respond to those on the front lines of war, hunger and increasingly common disasters like Sandy, Haiyan and Katrina.

The new international deal emerging from Peru is an important step, but it's not nearly enough to stabilize our climate, or rectify the injustice that those most affected are least responsible. Much like institutionalized racism and classism, truly solving climate requires a systematic change in our thinking. It requires us to not just demand change from our leaders, but to also look within ourselves to see the seeds of both problem and solution, and appreciate the common humanity connected to our daily decisions.

The good news is that we already know all the clean energy technologies and policies needed for an equitable climate future. What's still missing is enough collective will to implement and pay for clean solutions. We need to push our governments, companies, communities, investments and own lifestyle choices away from fossil fuels. Solar and wind power can now be cheaper than fossil options, but we need to reengineer our electrical grid much more quickly, demonstrating to the rest of the world that prosperity and climate equity can walk hand-in-hand, and forever dispelling the myth that development requires dirty energy. Perhaps most importantly, we need to talk about why climate matters with all our loved ones, reframing the issue from ivory tower environmentalism to an honest discussion of equity, justice, common purpose and shared responsibility.

We have the power to enact climate justice, but scaling up solutions depends as much on the stories we tell, and the alliances we forge, as it does on the technologies we have at our disposal. If we truly believe #BlackLivesMatter, then we have a duty to stop climate change as quickly as possible. Many more lives will be lost until we harness our collective outrage into collaborative action.