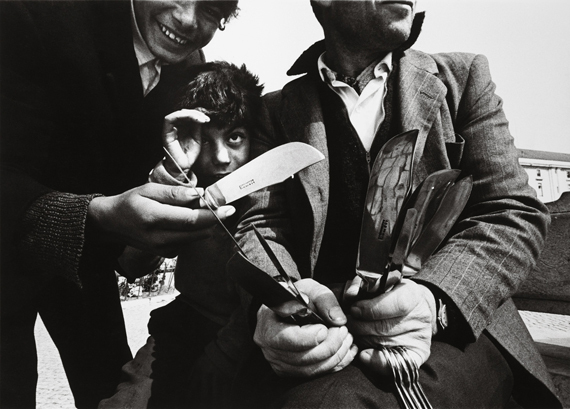

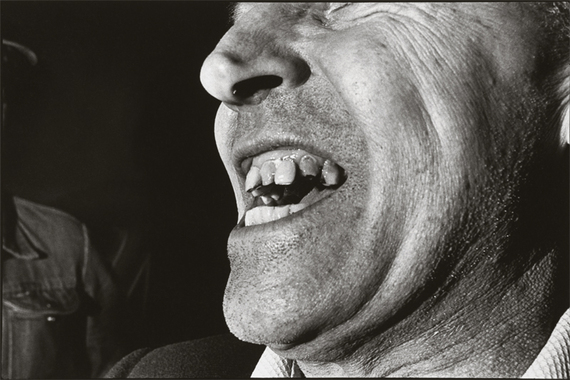

All Images (c) Mark Cohen, Courtesy of University of Texas Press

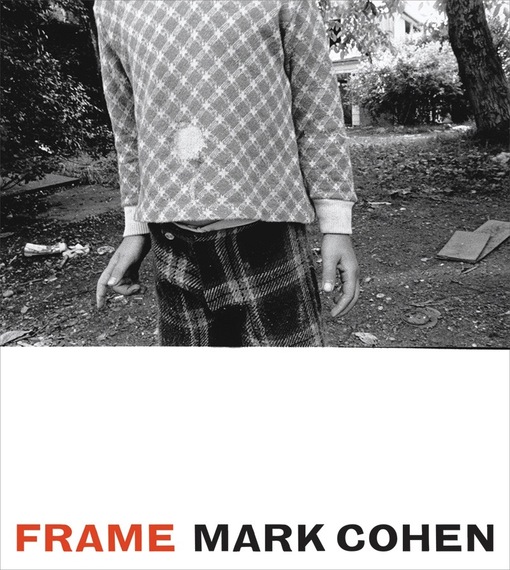

This is an exciting post for me. Why? Because I've had a copy of Mark Cohen's FRAME on my desk for nearly two months, but had my hands tied by the publisher not to write about it. Well, I'm happy to report that is now over and I can let loose on this wonderful retrospective collection from a true master of street photography - Mark Cohen.

Mark Cohen not only helped to define modern street photography, he was also one of a group of photographers who ushered in color photography and the acceptance of it as an art, not merely just a film for your grandmother to use at a birthday party. 35mm film for still photography didn't really get popular until about 1925, with the advent of the Leica camera. When one takes this into consideration, along with the acceptance of the idea that 35mm film really was the takeoff point for what we might call street photography, it is really no surprise that people like Cohen and others of his generation were the ones to notably push boundaries in new directions. Simply put, Mark Cohen was the man of the hour with 35mm street photography. Add to this mix some wide angle lenses and a blatant disregard for the viewfinder, and you have a recipe for truly groundbreaking aesthetics in photography - otherwise known as the work of Mark Cohen.

It may look easy to photograph snowflakes, or a few crumbs of bread next to a puddle (a photo Cohen considers one of his best) and I suppose it is. Now, try to make those photographs iconic. Ah, yes, there is the challenge. The confluence of time, medium (and its novelty at the time), along with a new approach to a unusual subject combines to convey iconic status here. Today making a photograph like this is near impossible, not only because we feel as though the images are too familiar - too exhausted - but because new technologies demand new deviation to achieve aesthetic uniqueness. Those street photographers trying to emulate people like Cohen today clutching to their M3 and a roll of film are helplessly doomed. Instead, the masters of today will be the photographers who embrace the current approach to image making (digital and its derivatives) and twist and bend it until something new and unseen - unfamiliar - emerges. That's how art, good art, is born. The 35mm frame of a few crumbs of bread abandoned on the sidewalk is done. It's taken. Like the blank canvass, you've missed your chance. This is why there will only ever be one Mark Cohen - and one Robert Rauschenberg, in the case of the blank canvas.

I've known Mark through casual correspondence for several years now. He's a wonderfully talented artist and a gentlemen of the highest order. When I heard of his new retrospective collection I simply couldn't help but get my hands on a copy. I'm glad I did. This book is the definitive Mark Cohen. A masterful and superbly curated (Cohen sequenced the photos himself) collection of over two hundred and fifty images - both black and white and color. All the iconic photographs are here and many others, some rarely seen, also find their home between these covers. An erudite and pleasantly colloquial introduction is provided by respected curator and writer, Jane Livingston. The introduction functions splendidly to place Cohen's work within the overall history of street photography, as well as to highlight some of his unique contributions to this increasingly popular form of photography.

One must keep in mind when viewing Cohen's work that his selective use of flash, blur, and haphazard framing, all essential to his vision, were entirely novel at the time. These highly emulated methods are commonplace today, if not overdone entirely, and that can easily diminish one's ability to read these photographs in their appropriate context - can diminish one's sense of awe and anomalousness. In precis, both Cohen's way of working, as well as his product, were entirely unfamiliar to a vintage audience. For example, Three Pieces of Bread By Puddle, 1975, is a striking image even today, in an age where this particular aesthetic is no longer strange or foreign to nearly any viewer. But imagine someone looking at this image in 1975? How almost silly it must have seemed - scraps of bread, blurry too! The image is a radical departure in photography not so much for what it depicts, but for what it doesn't, and for the notion that a serious artist would put this photograph forward in any kind of serious way. Cohen was not making a statement so much with what he was showing, the crumbs of bread - a puddle, but with his blatant disregard for the photographic paradigm of the time. Out of context the image is okay, interesting maybe, peculiar - in context the image is iconic, a complete game changer. In fact, this particular photograph, I suspect, is a lot more important to the history of photography than we realize. This photograph allows us to renew our sense of photographic seeing - to reapproach the photograph entirely. No small feat.

The physical book itself is a pleasure to hold. An attractive, but simple, slipcover (shown) hides a wonderfully elegant engraved black cloth hardbound cover with a color photo inlay. Red linen endpapers add and additional touch of richness. Oh, and the reproduced contact sheets in the front and rear of the book are a uniquely special touch. The University of Texas Press went all out for this book and it shows. The volume is well worth the very reasonable $85 price tag.

Now that I have you sold on the book. Let's talk to the man of the hour himself. Here's a transcript of a conversation I had with Cohen earlier this summer.

Michael Ernest Sweet: Mark, you've undeniably made significant contributions to the genre of street photography (and photography in general) how does that feel at this time in your life, to know you've had such a huge impact?

Mark Cohen: It feels very good to be a recognized artist. A photographer. I see pictures, even in newspapers and fashion magazines, with heads cut off, and close wide-angle cropping, everywhere, and when I first did this it was seen as very radical. Visibility took a long time to get, but I set up a lot of obstacles in my own way, unconsciously. Now there seems to be a lot of imitation of my style or technique and that feels okay too--to be seen and elaborated on in some way.

Michael: Yes, I was going to ask about how you feel to know that your work is so heavily emulated (even copied) by so many others today. Even my own work has been heavily influenced by your approach. Tell me, how did you get started in street photography?

Mark: My first influence was Cartier-Bresson. I saw his book, The Decisive Moment. Then I went to downtown Wilkes-Barre and made pictures on Public Square. It was where all the buses came into the city and so there were people everywhere and plenty of social activity. It was not like Mexico in 1933, but I could mix in with life all around and then develop those pictures.

Michael: Why so close, what lead you to this style of photography?

Mark: For an architectural commission I needed a 21mm lens and then I took it to the bus stop. I saw how close you needed to be to fill the frame. When I got this close the subjects began to react.

Also, at this time, 1972 or 1973, I started to carry, attached to the camera, a small flash unit that I could use to exaggerate the scene with dramatic lighting effects. The flash also enabled me to work even more quickly because the added instantaneous flash of light effectively made the exposure 1/1000th of a second at f16 so that everything was sharp and bright in the part of the frame that was key to the picture. I didn't have to stop moving to take the picture. A flux of intrusion, theater, and observation began to coalesce with these negatives.

Michael: Have you ever wanted to back up, to make photographs with wider views, more "classic" images one might say?

Mark: After a couple of years with the 21mm lens I saw that the intrusions into people's spaces was too frequent, and so I switched to a 28mm lens. This was a lot more comfortable. I had to learn to keep the camera level with these lenses because of the exaggerated distortions they made when they were tipped. I did it right. I did it all five minutes from my house. I had no real understanding of Madrid, but I went there and made pictures, and they are cool pictures but there is a local indelibility and truth about the Wilkes-Barre and Scranton pictures. Some are already classics.

Michael: Mark, are you still shooting on the streets?

Mark: Yes. I moved to Philadelphia and I am trying to learn how to work here. It is an infinitely bigger place. I need to fix up a little territory to work in. It is very difficult. Some very rough sections. I have been here about two years and now think I want to make an exhibit of the new pictures--which have been mostly made at the great distances required with the 50mm lens. There is no plan to my work and there is even in my own mind an incomplete understanding of what I am doing and what street photography actually is. I think it harbors an echo of surrealism in its accidentalness. I rarely look through the viewfinder.

Michael: Did you ever ask permission or "choreograph" any of your street photographs, or are they all truly candid?

Mark: Most, 99% are truly candid, but if I am very close, I might ask a deflecting question, like "can I get a picture of your ring?" Do it very fast--never put the camera to my eye, and have the ring as the approximate center of this unseen gyre of picture elements; buttons, windows, collars, necks, telephone poles, etc., to be discovered in the darkroom.

Michael: I completely understand that approach, I've worked that way myself quite often. It's a good middle-ground approach to fending off conflict. Have you ever had any significant altercations with strangers at the other end of the lens? Anything physical?

Mark: I have been pushed and shoved and screamed at but nothing serious. I am always aware of the edge and who to absolutely avoid. I know I am working without credentials, and very close to an invasion of privacy, even in such a public space as the street, but I am usually able to defuse the situation by explaining that it "is only my hobby."

Michael: Recent times have seen an explosion in street photography, do you think the genre is in for a radical change with the iPhone generation?

Mark: I never tried to look through an iPhone. It is hard to imagine a camera that is easier to see through the finder of than a Leica M-3. It fits in your hand at the end of your arm in a very natural way so as to position it perfectly and quickly. The digital images made by the millions each minute mostly never get printed. The selfies and grandchildren appear on the camera/phone screens. No one makes an album, or a portfolio of prints. A slim laptop is the modern way. It's all in the cloud-servers everywhere burning mountains of coal to keep it all sorted. It may be that the pace of street photography needs film. It is really pretty easy to develop, then discover, a roll of film and make a silver print. Make an object. But I just saw the new "film" Tangerine, made on the streets of Los Angeles, in a terrific and free candid, intimate way, made with an iPhone 5. That might move the French new wave two steps forward, so the future of street photography is unknown in the face of these new techniques.

Michael: Finally, you're also a rare bird in the street photography genre because you're known as much for your color photographs as you are for your monochromes. Was the color photography simply a product of the times, or were you working more deliberately with the move to color?

Mark: I had a commercial photo studio so I was always using color film. In about 1974 Kodak invented a 35mm ASA 400 speed film and this was the same speed as Tri-x so I could use it in the street in exactly, f-stop for f-stop, the same way. I shot a few rolls like this and then in 1976 the George Eastman House supported a project where I shot this new film for a whole year. Then I went back to black and white until 1987 when Fuji made a 1600 ASA speed negative film and I did another long series of negatives and prints with that film. My work was very deliberate in both black and white and color but the color pictures, which are very strong, were not seen until 2006, and took on an added significance when a portfolio of 30 dye transfer prints was produced.

Michael: Mark, thank you so kindly for your time and this insightful interview. It's always a pleasure to speak with you.

Mark: Thank you, Michael. I am very happy to have this chance to talk about my work and this new book from The University of Texas Press.

Mark Cohen started taking photographs when he was about 12 or 13. He's been at it pretty much ever since. His photography is in many major collections, including MoMA and the Whitney. He has published three previous books - Grim Street, True Color, and Dark Knees. Mark Cohen lives in Philadelphia.

Michael Ernest Sweet is a Canadian New York City-based writer and photographer. He is the author of two photography monographs, The Human Fragment and Michael Sweet's Coney Island, as well as more than one hundred articles, interviews and essays. Learn more at his website.