Frank Auerbach's retrospective at Tate Britain is, as expected, spectacular but made me think about how difficult it is for art institutions (museums and curators, in particular) to allow love, understood as that which motivates, on one side, artists to manipulate pigments to convey someone's presence and, on the other side, a sitter to sit for an artist. I guess uber professionalisation is to blame for this unawareness of what motivates artists to make art. In Auerbach's case this issue is paramount because as it is touchingly shown in Hannah Rothschild's documentary 'Frank Auerbach: To the Studio', he used the same people as models for his paintings throughout a career that spans more than forty years. Curated by one of his long time sitters, Catherine Lampert, the show is surprisingly clinical and, I would dare to say, detached and as such, it functions as a disembodied selportrait of this very self conscious man who all his sitters seem to love to the point of giving them a big chunk of their lives in exchange for a few paintings, a day out in Brighton once a year and a lifetime of immobile silence only for his gaze.

Hung throughout seven rooms according to the decade in which they were painted, Lambert's focus is on showing how his fluid use of paint (both oil and acrylic) changed in time. According to Lambert: 'Since 1960s Auerbach has scraped down the whole surface before the next attempt. Thus the final picture may look as if it were done at the first attempt but it has actually required 30, 50 or 200 separate versions that are judged not good enough. For landscapes, Auerbach uses information derived from drawings made on site in the morning prior to returning to the studio to paint. Five sitters come on different days to pose. Auerbach explains that a lot more is brought into play as the work goes on'. I think that it is in that 'lot more' that Lambert refers to where the key of the show lies. Unfortunately, she leaves that as an unchartered territory maybe because that is territory that she does not dare to walk. At this point, we might be talking about art professionals repressions and the inability to connect with their own bodies.

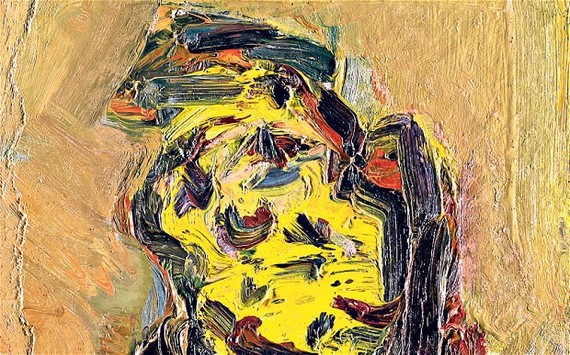

T.J.Clark's überformalist article for the exhibition catalogue ('On Frank Auerbach') makes it even more difficult to read these series as visual essays on the relationship between pigments, feelings and repression. Although, Clark ends up asking the right questions, his excessive formalism adds up to Auerbach's (and seemingly Lampert's) apparent detachment which, as I argue here, is the other side of a coin where love and the need to be loved seem to play in a loop. The problem is that Clark starts paying, maybe, too much attention to his landscapes and skips the issue of 'the human connection'. In his own words: 'There are tremendous Primrose Hill pictures in the show at Tate Britain. Several of them bring on the feeling I had back in 1968. Take the painting called Winter Evening, Primrose Hill Study, done over the winter of 1974-5. What struck me as incomprehensible about it on first sight was the raggedness and spikiness of the lines on its surfaces, like the spokes of a wind-wrecked umbrella. I could see that the lines, some of them, were meant to stand for trees in winter, but their abstractness did not look to be feeling for an order or consistency (or not one I could grasp) or a fluency, or a principle of growth and least of all, a groundedness or endurance in the things seen. Auerbach is a peculiar landscape painter. Nature for him seems to be instantaneous. It leaps out of the void. The paint contorts to capture it, but always what the impasto seems to be after is not the character of a scene or even the atmosphere but rather, its simply being there for once'. In other words, according to Clark, Auerbach's manipulation of pigments through impasto aims at conveying a type of presence that can only be captured in an instant (which is a key aspect of the medium of painting and differentiates it from other media such as film and music, to give just two examples) and is not representative or figurative.

This is obvious in his portraits whose sitters' facial features are almost unrecognisable because, according to Clark, Auerbach aims at 'capturing the sitter's other face or his or her face inside'. And adds: ' painting to a finish, in a canvas like this, seems to be a matter of extracting the non other face from the previous endless fluency. A crisp, corrected, unbroken hard edge. A unity at the cost of multiplicity, if that is what it takes to have unity'. To achieve unity, the fragmentary quality of details (facial features) must be resigned. There is where abstraction takes over and the synchronic aspects of painting take over. T.J.Clark draws the line of how far he dares to go borrowing from Robert Lowell when saying: 'We two, one cell here, lie....gazing into ether's crystal ball.... sky and sky and sky...till death'. Painting as a way of exploring the void. Death.

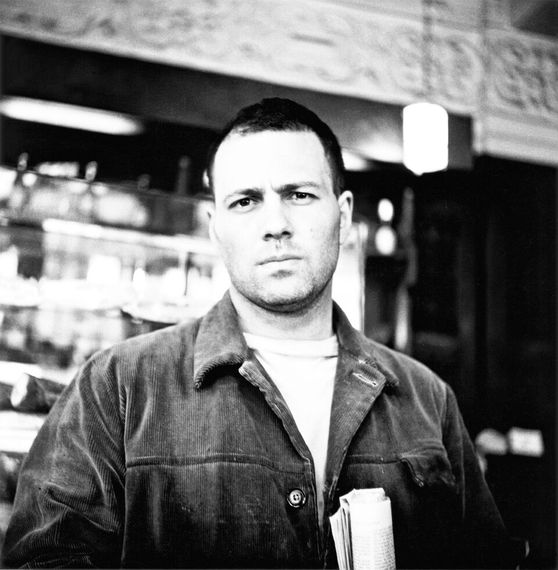

Although it is a well known fact that Frank Auerbach is a notoriously secretive artist, it is surprising that the show and the catalogue make no reference to his life and how an understanding of him as a person may give us an insight into a body of work that, for that precise reason, presents itself as hard to understand, bewitching, often difficult and always uncompromising. Auerbach has lived alone for the past 55 years in a small studio in Camden Town. He works 364 days a year in a furious race against time. He was born in Berlin in a bourgeois environment but both his parents died in Auschwitz after sending him to London when he was only 8 year old. Since then, he has run forward and never stopped working and his affective contact with human beings has been both silent and professional and always mediated by painting. In fact, he claims his art is his true autobiography and certainly his portraits reveal intimate relationships since the same people has posed for him for more than forty two years. Each sitter makes the journey across London to his studio on a set day, sixty two weeks a year without fail. There can be no better witnesses to Auerbach world than those people. They are the substitute of his exterminated family.

Gifted with stunning looks, young Auerbach's mysterious aloofness made his sitters fall in love with him and he loved them through paint. From this point of view, in spite of the fact that he wants his paintings to be framed behind glass, they should not be understood only as visual objects but as multi sensorial ones that can be touched, smelled and tasted, very much like during love making. From this point of view, Catherine Lampert seems to have paid too much attention to what comes out of the artist's mouth (to the point of having felt compelled to transcribe her conversations with him in the exhibition catalogue) instead of trusting her body and her eyes to finally convey the way a very talented man like Auerbach managed to love through pigments. Maybe she was too scared of her own feelings for him and she should have excused herself from this job. J A T