On February 23, 1895, three days after Frederick Douglass died in his Anacostia home and two days before his funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, just blocks from the White House, Richard F. Pettigrew from South Dakota rose on the Senate Floor to offer a resolution for immediate consideration.

"If it is to be passed at all it must be passed now," Pettigrew said.

The resolution read, "Whereas in the person of the late Frederick Douglass death has borne away one of our most illustrious fellow-citizens, who served his country long, faithfully, and honorably as citizen, diplomat and statesmen: Therefore, Be it resolved, That out of respect to his memory his remains be permitted to lie in state in the rotunda of the National Capitol between the hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. on to-morrow."

Arthur Poe Gorman, a senator from Douglass' native Maryland, was not interested. "Let the resolution go over," he said.

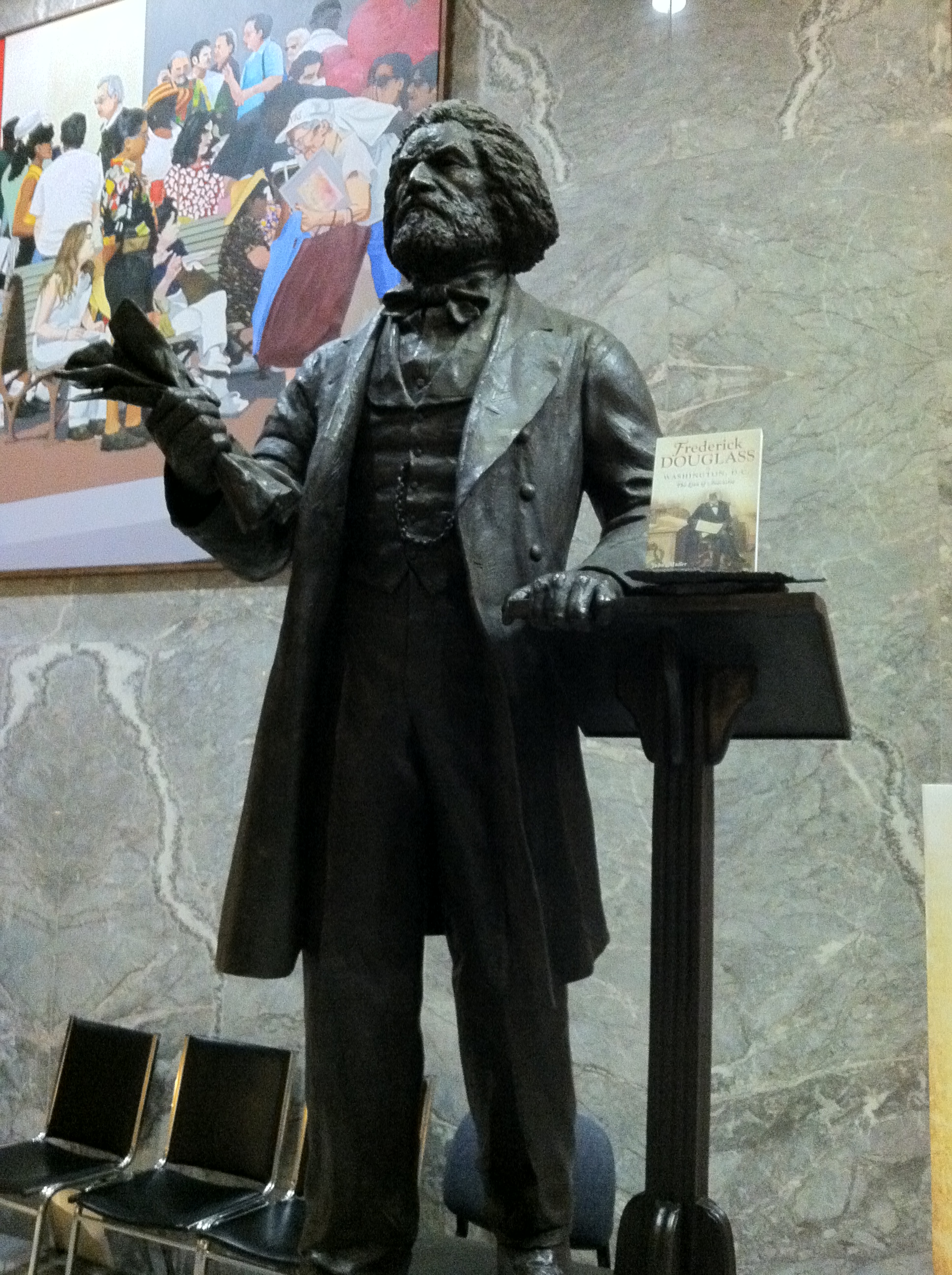

Now, more than a century later, the life of Frederick Douglass has come full circle; on June 19th a statue of his likeness will be permanently placed in the Capitol's Emancipation Hall joining 18 other men and women so honored. (In December 2007 the Capitol Visitor Center's central space was christened "Emancipation Hall" to recognize the memory of enslaved laborers who toiled to construct the building.)

Frederick Douglass' relationship with the United States Capitol was, in fact, curious and lifelong.

In his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Douglass revealed he finally came to understand who abolitionists were when he read in a Baltimore newspaper of their activities in Congress.

"In its columns I found, that, on a certain day, a vast number of petitions and memorials had been presented to Congress, praying for abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, and for the abolition of the slave trade between the states of the Union."

He would later tell this story throughout the country and across the Atlantic Ocean adding, "From this time I understood the words abolition and abolitionist, and always drew near when that word was spoken, expecting to hear something of importance to myself and fellow-slaves."

From a distance, Douglass knew the nation's capital city symbolized an inherent hypocrisy in the United States Constitution. In May 1846, while in England, Douglass said, "In the national District of Columbia, over which the star-spangled emblem is constantly waving, where orators are ever holding forth on the subject of American liberty, American democracy, American republicanism, there are two slave prisons."

Through the 1850s, while an editor, writer, orator and activist, Douglass did not waver in his faith that the day of jubilee would be realized, when American slavery would be forever abolished. During the Civil War Douglass met with President Lincoln on two separate occasions and was in Washington City to attend Lincoln's second inaugural in March 1865. With President Andrew Johnson wholly uninterested in citizenship claims of the more than four million freed slaves, Douglass and a group of prominent black men met him in February 1866, but were unable to persuade Johnson to change course.

After launching a newspaper in Washington, in April 1871 Douglass was appointed by President Grant to serve on the city's legislative council. This was the apex of Douglass' legislative career, although others had loftier aspirations on his behalf.

The year before, Hiram Revels from Mississippi became the first black American to join the United States Senate. Charles Douglass, Frederick's youngest son, had a front row seat to the swearing-in. "Many voices in the Galleries were heard by me to say, 'If it would only have been Fred Douglass,' and my heart beat rapidly." Charles urged his father to seize the moment as "the door is open, and I expect to see you pass in."

Never one to aggrandize his own self-importance, Douglass would later write, "I was earnestly urged by many of my respected fellow-citizens both colored and white, and from all sections of the country, to take up my abode in some one of the many districts of the South where there was a large colored vote and get myself elected, as they were sure I easily could do, to a seat in Congress--possibly in the Senate."

Writing in his 3rd autobiography, Douglass explained, "I had not lived long enough in Washington to have this sentiment sufficiently blunted to make me indifferent to its suggestions." However, Douglass trusted his instinct and knew his own limitations. He confessed, "I had small faith in my aptitude as a politician, and could not hope to cope with rival aspirants."

As a slave in Baltimore, Douglass had thought differently. In June 1870, he received a letter from an old church friend reminding him of his youthful ambitions. "Now, my dear brother and friend I have not forgotten the remark you made in the old frame house in Happy Alley rented by James Mingo in the debate one night you told me you never meant to stop until you got in the United [States] Senate."

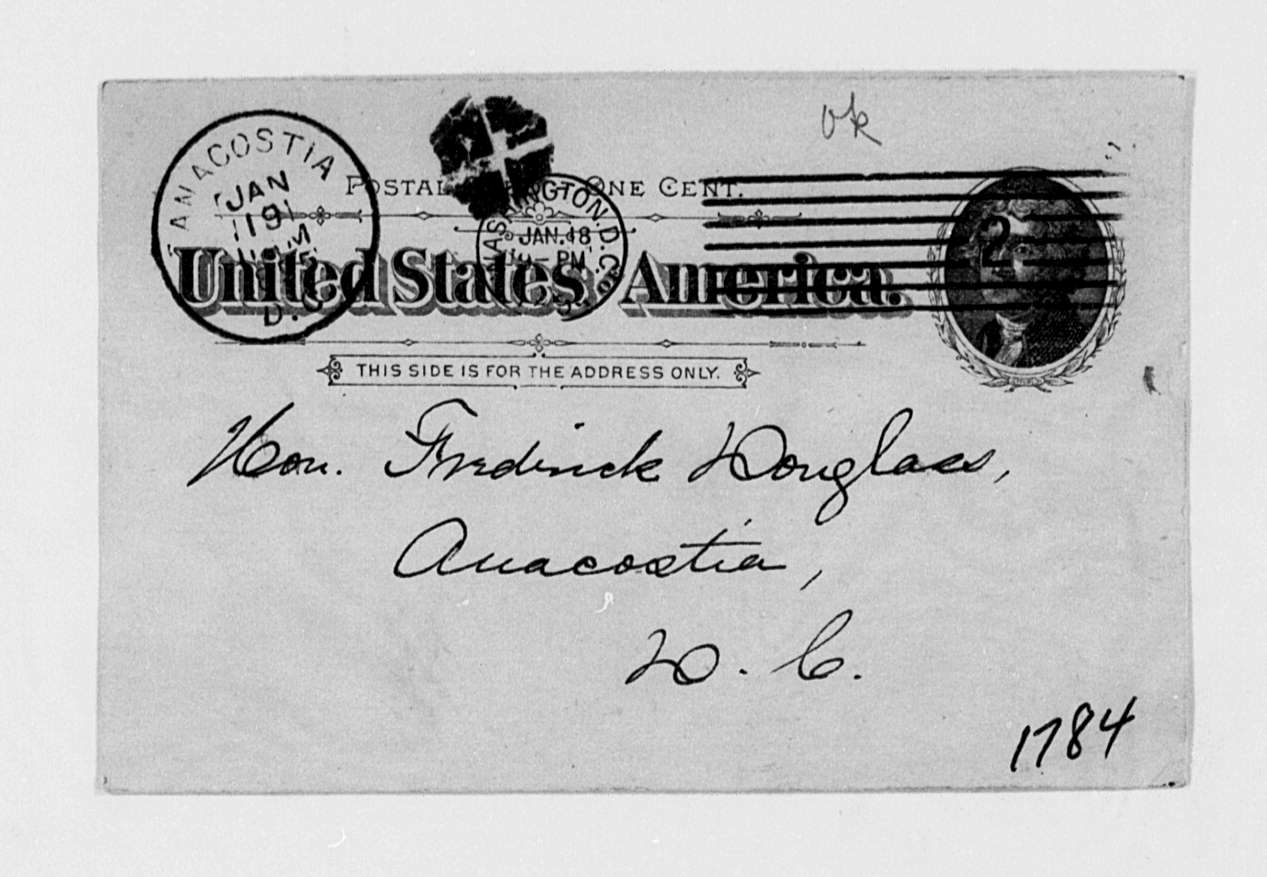

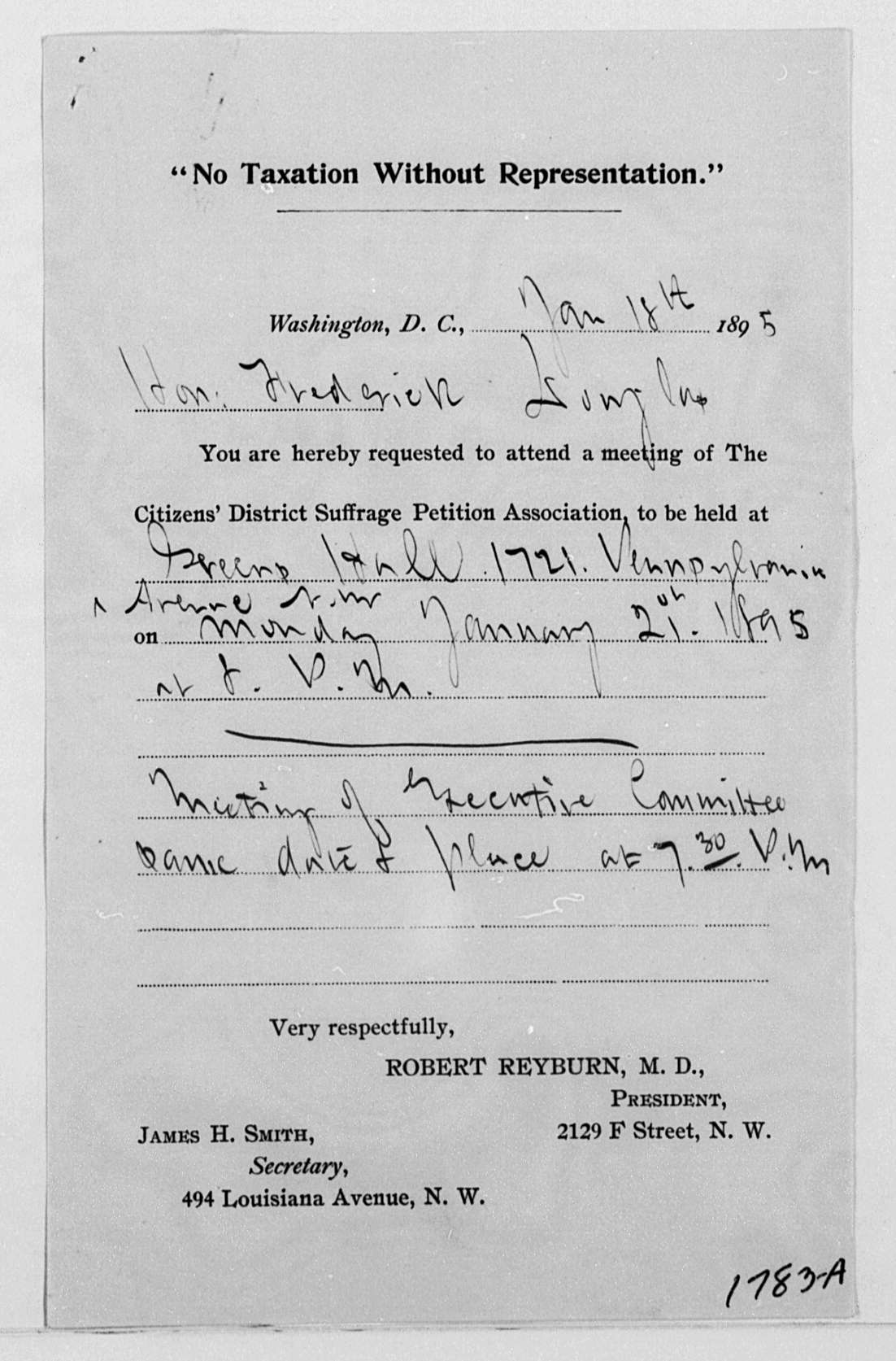

While living in the nation's capital for the last 25 years of his life, Douglass was a prescient voice for local representation. Less than a month before he died, Douglass attended a meeting of the District Suffrage Petition Association where he asked, "[W]hat have the people of the District done that they should be excluded from the privileges of the ballot box?"

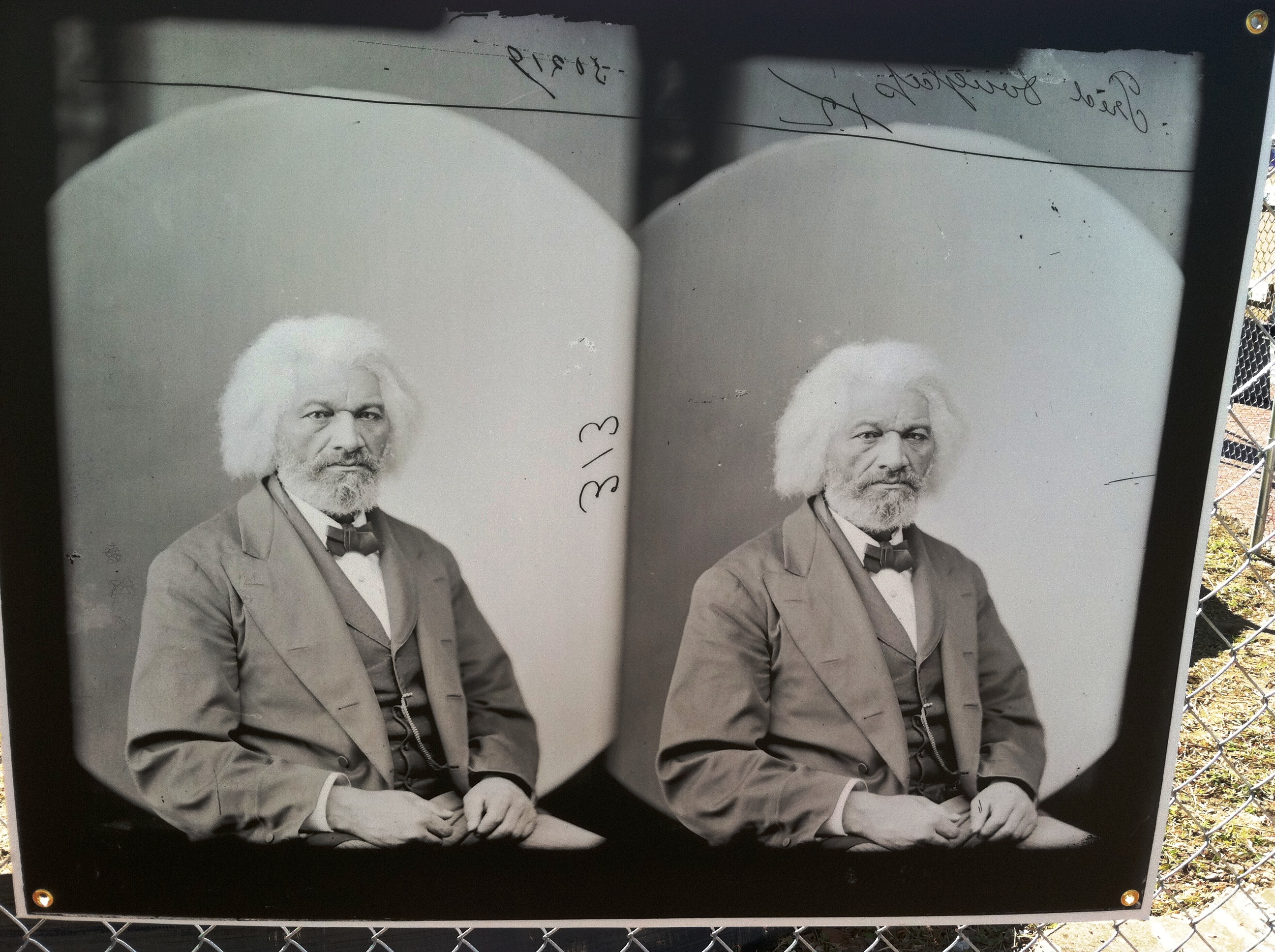

With the permanent placement of Douglass' statue in Emancipation Hall, there is a renewed groundswell of interest in his life and legacy capable of touching every man, woman, and child in the city. As the bicentennial of his birth approaches, Douglass will be discovered by a new generation.

Before the Frederick Douglass statue at One Judiciary Square moves to the U.S. Capitol, he takes time to read a new book about his life and times in Anacostia.