I found myself sitting in a shared office space with five strangers in Geneva, Switzerland, ready for the first activist meeting I had attended in, well, ever. I signed on to help organize a sister march to the grand March on Washington for January 21, 2017. Our group, mostly Americans, were concerned about the erosions in women's rights, civil rights and democratic institutions we saw around us. I guess I expected we'd already be painting signs and planning routes, something like a 'Hey, kids, let's put on a show!' moment, but the bulk of the work would take place, like so much these days, on an online platform. It felt exciting to be a part of something that was moving forward on a motto of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion.

How did someone who hasn't ever been on the organizational side of a march end up in that small room behind the main Geneva train station? Well, the obvious answer is through a Facebook page, a deep disappointment in some election results and a profound concern for the future. But the real reason is longer than that.

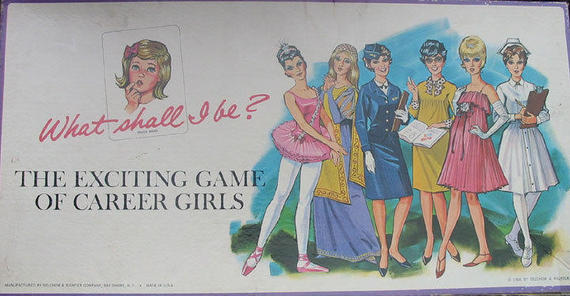

As a girl child of the Sixties - the early Sixties, to be specific - I came of age in a unique era in the United States. Women had achieved universal suffrage (after decades of fighting), but as I knew from my mother and grandmother, high-achieving girls were still expected to grow into secretaries or nurses rather than business leaders, or doctors. And in any case, work was only a prelude to becoming a wife and mother. When my mother stuck a Johnson-Humphrey campaign button to the ruffles of my diapered bottom, she was voting for the Great Society platform of civil rights and anti-poverty measures that nevertheless still didn't include what would later become known as women's rights.

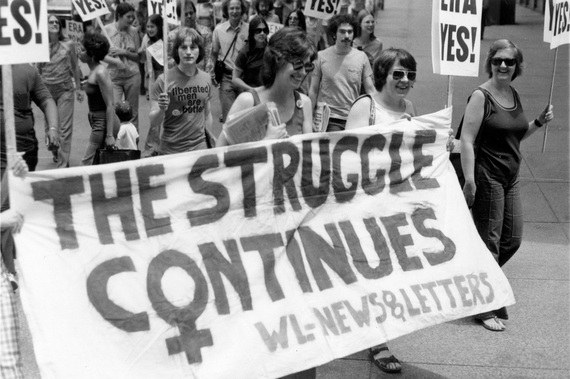

Another decade of activism changed that. By the 1970s, abortion had been legalized and the Equal Rights Amendment was up for discussion. As a white girl in a white suburb, my middle school teachers told the girls that they could really reach for the stars, and not just on the coat-tails of a pilot or doctor. We felt privileged, which we were. We felt on the cusp of something great, which we were.

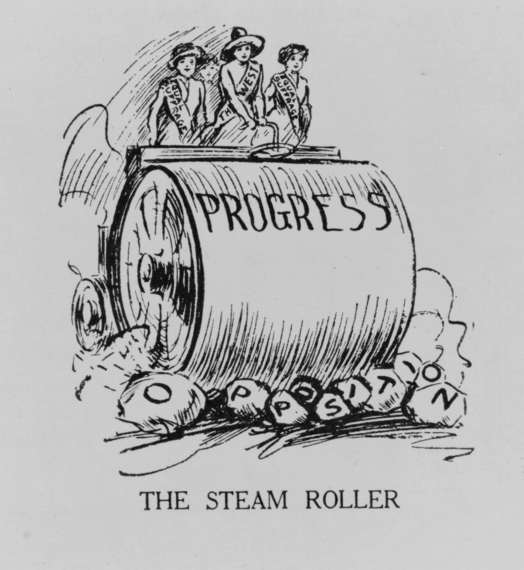

If you stood up for what you believed in, you could move history.

Gone were the days of my grandmother, top of her journalism class in the early 1930s, who was denied the top honor because the next student below her, a man, was considered more worthy as a future breadwinner. She was more than the equal of her fellow students, but her gender rendered her less valued. Gone the days when one of my mother's high school friends almost bled to death from an illegal abortion in Tijuana, my young mother getting her to a hospital just in time to save her life.

Because people stood up and fought.

The second organizing meeting for the newly-named Geneva Women's March for Dignity took place the following Saturday in the Bain de Paquis, a café on Lake Geneva. A line of activists slipped along a small bridge, slick with winter ice, to long tables in a steamy room. There were at least twenty of us, a range of ages, colors, nationalities, languages. Women, men, straight, gay, many experienced activists and human rights workers, many others like me, with exactly one meeting's worth of background.

The reasons people came out was as diverse as our group, mainly founded on a concern that instead of moving towards increased equality and building on the decades of hard work behind us, in many countries around the world we saw a retreat into the culture of fear, a longing for the fuzzy comforts of a fictional history which looks safe from a distance of forgetfulness and wishful thinking. Most of us were there because we agree that hard won gains in human rights can never be taken for granted.

As we divided up the tasks at hand, I thought of my mother.

My father was a singer--when I was very small, my mother brought home the steady money by working as a legal secretary. She was the main breadwinner, a successful young woman in San Francisco, but she couldn't get a credit card, open a bank account, or get birth control without a man's co-signature. Her employer, a well-known lawyer, could have fired her if she'd gotten pregnant and she wouldn't have had any recourse if he decided to sexually harrass her.

By the mid-1970s I was in my teens, and my mother told me I could do anything I wanted in life. But she also counseled me to learn to type, because then I'd be sure to have a job as a secretary if nothing else worked out.

At the third meeting for the Geneva March, we talked about how this grassroots organizing stuff takes a lot of patience; it's messy, people come in with different goals, it demands teamwork from a collection of strangers and newcomers. It demands a high tolerance for inclusiveness, which is appropriate, since that's one of the things we're marching for.

And at the same time, it's exhilarating to see the project coming together over a few short weeks. We have sponsors! We have a marching permit! We have emails coming in from all over offering help. We have our own logo with a skyline of Geneva! This is so much better than sitting home, sharing cynical Facebook posts and gravitating towards despair.

When I was in college, I canvassed for the National Organization for Women. It was during the Reagan era, and attempts were being made to roll back gains made in reproductive rights and civil rights. Most people I met were friendly enough, but one woman called her school age daughters to the door. "Look girls, this is what a feminist looks like. A traitor to all women." I'm not sure what she was trying to teach her daughters, but then she spit on me. Well. We women have always been among our own worst enemies. At the same time, I'll never forget the middle-aged man who, upon finding an activist on his doorstep, ran for a checkbook. "Never, ever give up on idealism, never stop fighting," he told me. "It's always worth it."

I'm the parent of a grown daughter now. When she was a teenager, she was in a public international school that is economically, socially and racially diverse, with over 90 countries represented, and at least twelve languages. With its wild collection everyone from refugee kids to local farmers' kids to kids of scientists and diplomats, it's just the kind of melting pot some people would have us fear.

A place like this doesn't happen by accident. Geneva has long been a center for human rights and progress. Our daughter came of age in a happy bubble of inclusiveness, and as the years pass I see what a generous, thoughtful group of young men and women have emerged from that school. I want that for everyone, not just the ones who happen to live in our corner of the world, who benefit from decades of human rights progress, open borders and a strong democracy.

At tomorrow's organizational meeting, we'll walk the entire length of the marching route, check security points, discuss logistics and last-minute planning. We'll talk about how we want to build on everything that's gone before us rather than looking ahead in anger or behind in false longing.

Never give up on idealism--it's always worth it.

The alternative is a life lived in fear and anger. We are stronger together, and it feels good to be standing up for that, and to be a group of strangers and new friends, joined in commitment, rejecting complacency, walking forward.

Where will you be on January 21? What will be your walk?