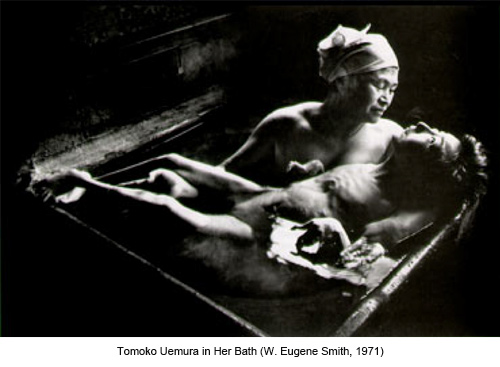

For me, the saddest stories are about needless human suffering, suffering caused by greed, hate, or more maddeningly, the inability of responsible people to act responsively. Minamata is that kind of story, encapsulated in a single and truly iconic photograph, by W. Eugene Smith. You might remember it as well, a picture of a young woman deformed as a result of industrial mercury poisoning, being bathed by her mother, who regards her with beatific and transcending love.

For those too young to remember, a Japanese factory polluted the Bay of Minamata, which caused illness, death and deformity in a nearby fishing village. This continued for more than thirty years, while the cause was covered up by both the factory owners and local officials. Smith's photographs, which appeared in Life Magazine in the early 1970's, finally brought change. He had gone to Minamata to live for two years with his Japanese wife, and while he was there company thugs attacked him, permanently damaging the vision in one of his eyes. The very worst thing was that even though Tomoko Uemura's photograph brought relief, change and compensation to other victims, her family was ostracized and her father later regretted that he had allowed Smith to take the photo. She died in 1977, at the age of 21.

I have been thinking about Minamata, because something similar is happening in Japan today. We all know that radiation sickness is a slow-motion phenomenon, but in the aftermath of the 3/11 tsunami and Fukushima nuclear disasters, we have lost interest in what is happening on the ground in Japan. We mustn't--the world community must stay involved.

This time, the consequences of the actions of public officials and a corporation, in this case TEPCO, (Tokyo Electric Power Company) will not be confined to a single village in Japan. Many Japanese do not believe what their government is telling them the truth about risks to their personal health. There are charges of Japanese government censorship and the withholding of critical information. Although traditional media does seem more controlled, information is available on the Internet, in citizen blogs, and also through non-profits that monitor the nuclear issue. Bands of citizens armed with Geiger counters and dosimeters are using mobile technology to provide readings that are published on the Web. Mothers in Fukushima share stories of their children's nosebleeds and unexplained illnesses, and their fears for the future. In spite of Japanese cultural biases, this time could be different, as a result of communications technologies that were not available 40 years ago.

Here are some of the important things that are being said on the Internet in Japan today, which you might not have heard yet:

1. No One Knows the Magnitude of the Disaster

According to an editorial in the Japan Times on November 8th:

In August, the Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan estimated that the Fukushima accidents released a total of 570,000 terabecquerels of radioactive substances, including some 11,000 terabecquerels of radioactive cesium 137. But a preliminary report issued in late October, whose chief writer is Mr. Andreas Stohl of the Norwegian Institute for Air Research, estimates that the accidents released about 36,000 terabecquerels of radioactive cesium 137 from their start through April 20. It is more than three times the estimate by Japan's Nuclear Safety Commission and 42 percent of the estimated release from Chernobyl.

This editorial underlines the pervasive lack of trust in government, in terms of the extent of the disaster, and its effects on human health. The editorial goes on to describe official waffling about what exactly is a safe amount of radiation exposure:

As for internal radiation exposure from food and drink, the Food Safety Commission on Oct. 27 said that a cumulative dose of 100 millisieverts or more in one's lifetime can cause health risks. But when it had mentioned the limit of 100 millisieverts in July, it explained that the limit covered both external and internal radiation exposure. Its new announcement means that the government has not set the limit for external radiation exposure. It also failed to clarify whether the new dose limit is safe enough for children and pregnant women.

Japan's Parliamentary Secretary for the Cabinet Office Yasuhiro Sonoda drinks a glass of decontaminated water taken from puddles inside the buildings housing reactors 5 and 6 at the Fukushima No. 1 plant.

2. Fukushima Is Still Not Safe

Tepco has recently uncovered high levels of radiation at its No. 3 plant in Fukushima. The latest reading, 610 millisieverts per hour, is higher than the maximum 500 millisieverts recommended for emergency workers. Basically, we still don't know how dangerous things are, and most Japanese assume that TEPCO is either not telling the truth or they are incompetent. There is not a clear explanation of what happened, and people are demanding to know the fate of emergency workers who were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation.

In spite of the fact that the Japanese government has hired a public relations agency to encourage redevelopment in Fukushima, the locals are clearly not buying the safety promises. According to Kyodo News, 1 in 4 Fukushima residents have no intention of ever returning to live in the area--they don't trust what the government is telling them.

The most common reason for not wanting to go back -- cited by 83 percent of the respondents, who were allowed to give multiple reasons -- was the difficulty of decontaminating the area. The second-most common response was lack of trust in the central government's declarations of safety. No. 3, chosen by 63%, was that they can't expect the nuclear crisis to be resolved. Taken together, the three top reasons indicate serious doubts about the government's ability to manage the disaster

Still, some people will always figure out a way to make money in a crisis. In a moment of unintentional corporate hilarity, Sanwa has decided to manufacture a Geiger counter in Otama, Fukushima, to help the residents protect themselves from "hot spots". Who, I wonder, will measure the radioactivity of the Geiger counters themselves?

Still, some people will always figure out a way to make money in a crisis. In a moment of unintentional corporate hilarity, Sanwa has decided to manufacture a Geiger counter in Otama, Fukushima, to help the residents protect themselves from "hot spots". Who, I wonder, will measure the radioactivity of the Geiger counters themselves?

Thyroid cancer is a particular concern in the young. The Fukushima government has distributed dosimeters to 280,000 children ranging in age from infants to teenagers so that they can monitor their own gamma ray levels. I am trying to imagine a four year-old trying to manage this. (By the way, a dosimeter is like an odometer, it measures cumulative radiation exposure, while a Geiger counter is like a speedometer, it measures radiation at a particular place and time.)

One citizen group, Moms to Save Children From Radiation has a website that is also available in English and gives you a good idea of the discussion that is going on. The government cannot decide on safe levels of exposure for adults, but children and pregnant women are a special worry because very little is known about what constitutes "safe" for this group. Japanese who might be willing to sacrifice themselves, are unwilling to sacrifice their children. I read a story of one mother who left Fukushima with her children for Sapporo. Her husband stayed behind to teach school, where students play outside with few basic precautions. An added problem that traps families--Japanese cannot walk away from their mortgages, as they can in this country. So resettlement is an economic nightmare for many families, and some who would like to flee the area are unable to do so. This is something that could and should be handled by national policy.

3. The Threat Is Not Just in Fukushima

Lest you think that the damage is limited to the Tohoku region, you should know that the Japanese government has asked everyone in Japan to sacrifice in light of the national emergency. 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, debris from the disaster area is being incinerated across 16 prefectures in spite of local protests. At the end of August, the Japanese Environment Ministry asked 469 incinerator operators to measure levels of Cesium isotopes in their ash. Very high levels were found in 42 plants in 7 prefectures, and lower but dangerous levels in other prefectures including Tokyo. I am not a nuclear scientist, but I do not believe that putting contaminated radioactive garbage into an incinerator will do anything except propel radioactive ash into the atmosphere.

The ministry is "discussing how to safely bury incinerator ash and dust with cesium levels above 8,000 becquerels/kg. Local governments have been instructed to temporarily store their ash and dust at disposal sites until the panel reaches a conclusion." They have all the time in the world, because the half-life of cesium 137 is about 30 years.

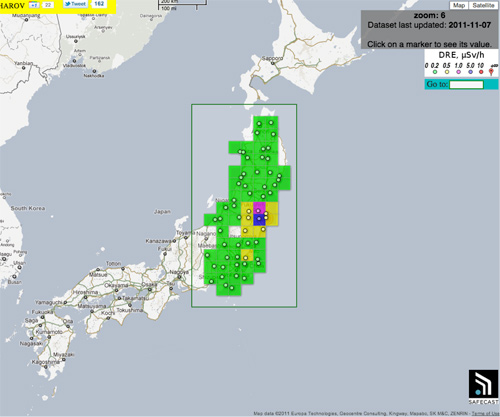

A non-profit, Safecast has organized mobile monitoring of radiation levels throughout Japan by volunteers, and they have maps that show relative levels of contamination in Japan and at other spots around the world.

4. Hot Particles in Seattle

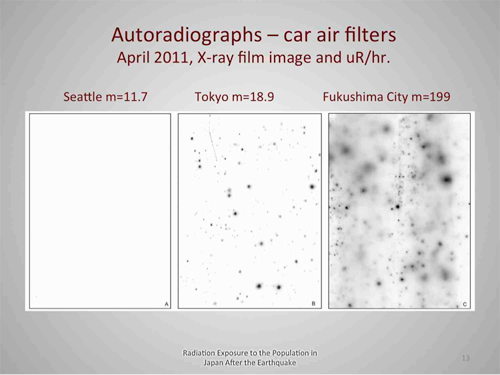

Fairewinds, a Vermont based non-profit, has highlighted a recent study about hot particles released as a result of the Fukushima accident which have turned up in Seattle and Boston. Marco Kaltofen, PE , Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, presented to the American Public Health Association.

The Fukushima nuclear accident dispersed airborne dusts that are contaminated with radioactive particles. When inhaled or ingested, these particles can have negative effects on human health that are different from those caused by exposure to external or uniform radiation fields. A field sampling effort was undertaken to characterize the form and concentration of radionuclides in the air and in environmental media which can accumulate fallout. Samples included settled dusts, surface wipes, used filter masks, used air filters, dusty footwear, and surface soils. Particles were collected from used motor vehicle air filters and standard 0.45 micron membrane air filters. The samples of Japanese children's shoes were found to have relatively high radiocesium contamination levels. Dusts containing radioactive cesium were found at levels orders of magnitude above background more than 100 miles from the accident site, and were detectable on the US west coast.

You can watch a video by Arnie Gunderson, an engineer who is chairman of Fairewinds, which explains these concerns in detail.

Berkeley also hosts a lively blog on the subject.

5. The Japanese Government is Still Committed to Nuclear Power

With all this mess, I had thought that Japan was winding down its dependence on nuclear power. Evidently not.

Here is an excerpt of an article by Takao Yamada that appeared November 8th in the Mainichi newspaper about the state of funding for nuclear projects in Japan:

Those of us who believed that experiencing a disaster of untold consequences and being subjected to a massive amount of criticism would result in significant cutbacks in nuclear power-related budget requests are too trusting. The fiscal 2012 requests are built on a spirit of maintaining the status quo, and "putting the lives of those in the nuclear industry first." There's no way we can accept such politics.

Looking through budget requests that finally became available in their entirety at the end of September, I noticed that the request for funds relating to Monju, a fast-breeder reactor with a dismal track record and equally dismal prospects, stood at 21.5 billion yen, the exact amount the budget allocated for the project in fiscal 2011 (previous to the disaster). Meanwhile, the budget request for nuclear fusion projects, which have even bleaker prospects than Monju, is 33.2 billion yen, twice that of the budget for the current fiscal year. This means that the fiscal 2012 budget allocation requests for all nuclear power-related expenses -- which do not include any recovery and reconstruction costs -- total around 440 billion yen, the same level as the current fiscal year.

Looking through budget requests that finally became available in their entirety at the end of September, I noticed that the request for funds relating to Monju, a fast-breeder reactor with a dismal track record and equally dismal prospects, stood at 21.5 billion yen, the exact amount the budget allocated for the project in fiscal 2011 (previous to the disaster). Meanwhile, the budget request for nuclear fusion projects, which have even bleaker prospects than Monju, is 33.2 billion yen, twice that of the budget for the current fiscal year. This means that the fiscal 2012 budget allocation requests for all nuclear power-related expenses -- which do not include any recovery and reconstruction costs -- total around 440 billion yen, the same level as the current fiscal year.

Will This Time Be Different?

So this story ends where it began, in Minamata. A seemingly blind and overwhelmed government is working hand-in-hand with an industry fighting for its survival. This week in Shirakawa, Fukushima Prefecture, a very special exhibition will be held, organized by its citizens.

"We, the people in Fukushima Prefecture, now suffer the damage inflicted by money-driven business operations as were the people of Minamata," said Mari Obuchi, a member of the local organizing group of the exhibition. "We hope the visitors to the exhibition will find clues about tackling the radiation issue through the experiences of Minamata."

It would almost be worth travelling to Fukushima to see it.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog.

What's Next? Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy by David Hale and Lyric Hale is available now from Yale University Press.