By David Selden

There is something about the Theremin, both its sound and the manner of its playing, that is almost comedic. An all-electric musical saw, its over-familiar, spooked warble has become a staple of B-movie sound effects. A "good vibration" quickly reached for as shorthand for the uncanny, curdling quickly into cliché or cute eccentricity. The Theremin was and is however the sound of the future, albeit the sound of the future as first heard in the technologically-optimistic Soviet Russia of the 1920's. Whether in Miklós Rózsa's scores for Spellbound and The Lost Weekend, Bernard Hermann's work in The Day the Earth Stood Still (or indeed Jimmy Page's diabolic dabblings (iii) the eldritch tones of the Theremin have served the movies well as a signifier that something is amiss.

Nonetheless, unlike other early electronic instruments such as the Telharmonium, Trautonium and even the Ondes Martenot, the sounds of Léon Theremin's infernal circuitry are anything but forgotten, in fact they border on ubiquity (i). Put into commercial production first (unsuccessfully) by RCA and then by Robert Moog (ii), the Theremin, the hot new sound of yesteryear, borders on the pervasive.

In popular music the Theremin's antenna has been used and abused, by the Beach Boys, to evoke the carefree pleasures of the Californian summer and by Hawkwind (and Lothar and the Hand People, amongst many others) to summon UFO's. Contemporary exponents include Dorit Chrysler and Radiohead to name but two. For serious Thereminophiles however the extraordinary expressivity of the instrument commends it to the classical repertoire.

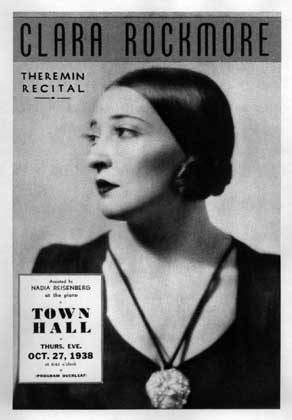

Watching Clara Rockmore tease sounds out of the ether whilest her sister (the accomplished pianist Nadia Reisenberg) accompanies her in a loud floral print dress, the viewer almost feels as if they are intruding. Rockmore's face is lined with concentration or lost in ecstasy as her painted nails pluck at the air, summoning a remembered violin. There is something dated but also strangely timeless about the tones that she evokes.

Taped at home in front of a small audience, Dr Thomas Ray, Robert Moog and her nephew, the broadcaster Bob Sherman, this performance feels like a swansong (though Clara would survive her sister by fifteen years).

To some degree the Bel-Canto style of her playing cannot but help recall the schmaltz and bathos of the classic Hollywood string section - it is simply the nature of the instrument. Quivering with emotion, Rockmore summons up melancholy ghosts, a suburban medium miming escape, swimming through a thin syrup of emotional ectoplasm. To contemporary ears it might seem a little histrionic, but there can be no doubting its sincerity.

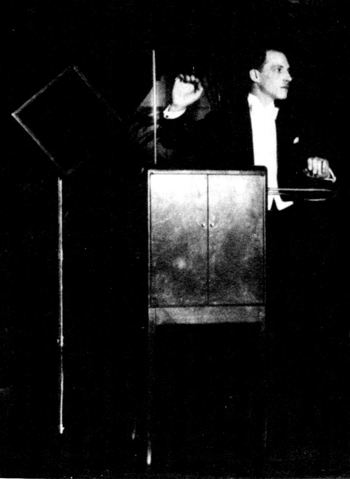

The Theremin had started life as a by-product of Soviet research into proximity detectors. In 1920 the young physicist, Lev Sergeyevich Termen (later to be known as Léon Theremin), demonstrated his invention to his amazed professor and fellow students.

Trying to remember the notes on the cello from Camille Saint-Saëns' Le Cygne, Theremin showed that the difference between the frequencies of two radio oscillators (one fixed, the other controlled by the proximity of the performer) could be turned into audio signals. The demonstration was musical but the principle went on to have other applications.

After a favorable reception at various electronics conferences, Theremin was asked to present his "Termenvox" to Lenin, who was so impressed he began to take lessons. Theremin would eventually be dispatched around the world as an ambassador for Soviet technology and its latest extraordinary invention, the first viable electronic instrument.

In 1915, five years prior to Theremin's performance, a four-year-old Lithuanian girl, Clara Reisenberg, had been the youngest student ever to be admitted to the Saint Petersburg Imperial Conservatory. She was so small that she played her audition standing on a table but her perfect pitch and precocious talent won her a place under the violinist Leopold Auer.

After the revolution, Clara's family fled Russia, their passage in part paid for by concerts that she would perform with her older sister Nadia. The Reisenbergs eventually arrived at Ellis Island on December 19, 1921 and Clara resumed her studies with Auer in New York. Unfortunately, shortly before her American debut she developed a problem with her arm. The arthritic condition, exacerbated by childhood malnutrition and obsessive practicing, eventually forced her to abandon the violin.

By 1928 Léon Theremin had acquired an American patent on his device and sold the commercial rights to RCA. Although the Theremin was not a commercial success in America (the timing of its release, at the end of The Crash, probably did not help its prospects) the Theremin won many admirers, including Clara.

When the two met she demonstrated such aptitude for the notoriously difficult instrument that he presented her with an RCA model as a gift. Observing that she was a violinist, Theremin even offered to reverse the poles of the device so that she could produce vibrato with her left hand, as she was accustomed. She declined, saying, "other people who will follow should play it the way you invented it." (iv)

A few years later, despite having rejected Theremin's proposal of marriage in favor of attorney Robert Rockmore, Clara was to persuade the inventor to build her a custom version extending its range and sensitivity (v). Theremin was later to write of Clara that she played liked an angel.

Following recitals with her sister, Clara Rockmore would go on to become the acknowledged virtuoso of the instrument, completing three coast to coast tours with Paul Robeson and making orchestral appearances in Philadelphia, Toronto and New York, where she premiered a concerto written especially for her with Stokowski conducting (vi).

Theremin, meanwhile, had disappeared. In 1938 he left New York under somewhat mysterious circumstances. Whether because he was homesick, anxious about the coming war, in financial difficulties or kidnapped by the KGB, he had in fact been put to work in a secret laboratory in the Gulag, as rumors of his execution were widely circulated.

Unknown to his friends in the West, Theremin (long thought dead) would continue to work for the KGB, building surveillance devices until 1966. The most successful of these ("The Thing") had been discovered in a carved wooden seal that Soviet schoolchildren had presented as a "gesture of friendship" to the American ambassador in Moscow in 1945. The listening device had been in place, and fully functional, for 7 years before its discovery.

As early as 1962 Rockmore and her husband had a clandestine meeting with Theremin in Moscow. Sadly, a year later, Bob Rockmore was to die after slipping on ice, a loss from which Clara never fully recovered.

Theremin would eventually retire from the KGB to take up a position at the Moscow Conservatoire but in 1967, "exposed" by the New York Times (vii), he was summarily dismissed. The director stating that, "electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution" (viii)

Interest in the Theremin was growing worldwide with successful record releases in the 70's and 80's, initially supervised by Bob Moog. In 1991, Rockmore and Theremin (the latter aged 96) would be formally reunited in New York, at the arrangement of filmmaker Steven M. Martin whose Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey (1993) sparked a further revival of interest in the instrument. Tragically, the film received its premiere the same year as Léon Theremin's death.

Clara Rockmore died at the age of 87 in 1998, but the fascination of a subsequent generation with the warbling, haunted tone of the Theremin persists. Today Lydia Kavina, the granddaughter of Léon Theremin's first cousin, continues to perform the classical Theremin repertoire, which includes works by Varèse, Martinů, Percy Grainger and Christian Wolf.

That Kavina's repertoire also includes Theremin scores by Rózsa and collaborations with Messer Chups (not to mention appearances on the soundtracks of Tim Burton's Ed Wood, David Cronenberg's eXistenZ and Brad Anderson's Machinist) suggests that the Theremin's quirky musical vocabulary of swooping glissandi and quivering portamenti will continue to be heard long after the sounds of other electronic instruments of its vintage have been forgotten.

Bob Moog interviews Clara Rockmore (1977). Theriminvox

In Clara's Home - Her Last Years, and the Summer of 1997 .

Steve J. Sherman ( 2007). Thereminvox

Theremin: ether music and espionage .

Albert Glinsky. University of Illinois Press (2000)

Synthmuseum

Notes:

i

It is not entirely true to say the sounds of the Ondes Martenot are forgotten as Olivier Messiaen's Turangalîla-Symphonie remains part of the classical repetoire and it has made several guest appearances on Radiohead albums, nonetheless it is not as easily identifiable for most listeners as the Theremin.

As for the Telharmonium, the fact that the Mark III version weighed 200 tons and occupied an entire room, as well as its immense power requirements, inevitable limited the scope of its development and the project was eventually abandoned.

"No recordings of the Telharmonium have survived. In 1950 Arthur T. Cahill, Thaddeus's brother, tried to find a home for the only remaining instrument, the first prototype. But nobody was interested so he sold it for scrap".

ii On April 1st 2011 the Moog company unleashed the PolyTheremin on an unsuspecting world. Wired

iii Fans of Page should be sure to checkout his soundtrack for Michael Winner's unpleasant revenge fantasy, Death Wish II.

iv Clara Rockmore: In Her Own Words. The Nadia Reisenberg and Clara Rockmore Foundation

v As a musician, though, I was not satisfied with the RCA model (of the theremin). I could not tolerate the left hand, which I called "molasses" -- there was no way of breaking the sound, so everything had to be played glissando. I needed a faster left hand, to permit staccato, and I wanted low notes as well as high. All I had to do was to inspire Theremin, to explain what I needed, and he, being the genius that he was, built for me a much more exacting instrument. Controlling it was much more difficult, but it was far more responsive, and therefore musically more satisfying. I had to make -- and then meet -- my own standards; I had to win the public over into thinking of the theremin as a real, artistic medium."

Clara Rockmore: In Her Own Words. The Nadia Reisenberg and Clara Rockmore Foundation

vi The Pastorale from Anis Fuleihan's Concerto for Theremin. (1942) is to be found on Clara Rockmore's Lost Theremin Album. Bridge Records 2006

vii New York Times. Harold C. Schonberg. 25th April 1967