How do we honor the dead artistically? In some cases, we commission artists and architects to erect monuments to the memories of those we have lost. Monuments can range in size from a simple gravestone to an Egyptian pyramid.

Whether one man (Shah Jahan) creates the world's most famous mausoleum (the Taj Mahal) to honor the memory of his beloved wife (Mumtaz Mahal) or a nation designs and erects a structure such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the dead are most often memorialized in marble and stone. From Holocaust memorials to tombs of unknown soldiers, from San Francisco's AIDS Memorial Grove to the memorials honoring those whose lives were lost during the sinking of the RMS Titanic, architects, sculptors, and landscapers have all designed monuments to those who died prematurely.

It's the thought that counts.

What music honors the dead? "Siegfried's Funeral March" (from Richard Wagner's opera, Gotterdammerung) quickly come to mind. So does Death and Transfiguration, the magnificent orchestral tone poem by Richard Strauss. Here's Audra McDonald singing "My Man's Gone Now" from George Gershwin's 1935 opera, Porgy and Bess.

Mozart, Verdi, Brahms, Cherubini, Berlioz, Dvorak, Fauré, Britten, Penderecki and Andrew Lloyd Webber have all composed requiems honoring the dead. Yet sometimes the simplest music speaks the loudest. Here is a clip of the great Ethel Waters singing Irving Berlin's show-stopping "Supper Time" (which was written for the 1933 Broadway musical, As Thousands Cheer).

The music that accompanies a documentary often adds a powerful emotional element to the viewing experience. Two new movies celebrating the dead were recently screened at Bay area film festivals. Each stands on its own as a magnificent piece of documentary film. Their scores, however, were so integral to the viewing experience that it is hard to separate them from the films they enhanced.

* * * * * * * * * *

One of the places people least look forward to visiting is a cemetery. It doesn't matter whether they are attending a funeral, unveiling a headstone, or being buried in a graveyard plot. Cemeteries just don't rank very high on most people's lists of places to go and things to be done. In June, however, the Spoon River Project (a new adaptation by Tom Andolora of Edgar Lee Masters's 1915 Spoon River Anthology) was performed at night in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery.

Written and directed by Britta Wauer, In Heaven Underground: The Wiessensee Jewish Cemetery is a marvelously entertaining documentary about a truly historic burial ground. It is as charming and delightful a film as one will ever encounter -- especially among those films aimed at documenting the dead (Wauer's poignant movie recently won the coveted Panorama Audience Award for Best Documentary at the 2011 Berlin International Film Festival).

Poster art for In Heaven Underground:

The Weissensee Jewish Cemetery

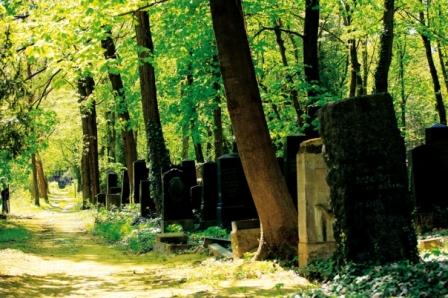

Dedicated in 1880, the Weissensee Jewish Cemetery has been in continuous operation under Jewish authority for more than 130 years. With over 115,000 graves sprawled across 100 acres of an urban forest of deciduous trees, it is the largest active Jewish burial ground in Europe. Amazingly, this Berlin cemetery and its archives were left undestroyed during the Nazi regime (perhaps partly because of local superstitions about a golem residing on its grounds).

A quiet part of the Wiessensee Jewish Cemetery in Berlin

Today, the Weissensee's visitors range from American and Israeli Jews seeking the graves of long-lost relatives to German ornithologists determined to track the population and lifestyles of the cemetery's resident goshawks. In her director's statement, Wauer writes:

"It is more than a challenge to fairly handle the fates of more than 115,000 departed souls and their relatives in a film. There is no chance of being comprehensive. A list of famous names, a sequence of lifetime achievements or recounting sad deaths do not make for an interesting film. Yet Weissensee has earned this. The screen should not to be filled with graves, ivy, and gravel, but with people telling of the rich lives that were once led in Berlin. For me it's a matter of personal connections. The idea was one of pursuing some few fates and letting protagonists who were personally connected to the dead tell the tale. People with memories, feelings, and thoughts are central. They should play the main role in the film and make plain to the viewer what is precious about Weissensee.

Naturally, the era of Nazi dictatorship overshadows all other events. But the film does not want to restrict itself to recounting deaths from those years. To reduce the dead of Weissensee to their sad ends is a falsification. Many of those buried there completed unusual things, achieved something special, or experienced something strange. The film also wants to tell of funny, absurd, and thoughtful moments, and of a great love -- one without a happy ending."

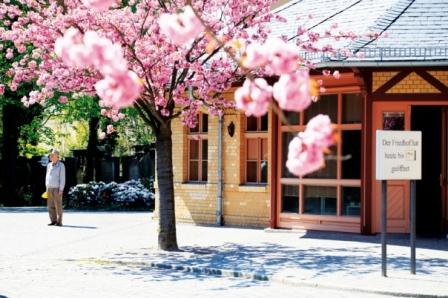

A tree blooms in the Weissensee Jewish Cemetery in Berlin

In Heaven Underground benefits from a wealth of archival footage showing life in Berlin from the earliest days of moving film up to World War II. A particularly moving section of the film describes how those few Jews who remained in Berlin after World War II were affected by the division of the city and the erection of the Berlin Wall. An English Jew who hoped to visit his family's graves was so afraid of trying to cross into East Berlin that he hired a guide to accompany him on his journey.

Throughout the film, the cemetery's aging Rabbi William Wolff (who acts like a spry garden gnome) provides humorous insights into the Weissensee's history as well as his own opinions on life, death, and what to expect from a cemetery.

Rabbi William Wolff

But it is the original score by Karim Sebastian Elias that sets so much of the film's tone in critical scenes. With segments that range from mischievous to mournful, from merry to melancholy, Elias's music does such a splendid job of showcasing Weissensee's history and natural beauty that viewers may be shocked to find themselves laughing and smiling throughout a documentary about the final resting place of so many European Jews.

Whether learning how access to a cemetery can give teenage boys equal access to free beer (or how the children whose families lived at the cemetery learned how to compete in sports events during World War II), In Heaven Underground provides astonishing insights into suffering, survival, symbolism, and cinematography. Here's the trailer:

* * * * * * * * * *

As the son of a science teacher, there was no way in hell I was going to miss a screening the British Film Institute's newly-restored print of The Great White Silence. Combining film clips and stills taken by Herbert Ponting (the 1910-1913 British Antarctic Expedition's official photographer and cinematographer), this film is so much more than a documentary about history in the making or man's quest to explore the unknown. A century after the fateful expedition, it offers viewers a surprising way of gauging how far we have come thanks to the work of explorers and scientists.

Think, for just a minute, about what primitive navigational tools were available to seagoing explorers like Leif Ericson, Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and Sir Francis Drake. Then take a moment to appreciate how computer technology has allowed us to put a man on the moon, land robotic vehicles on Mars, and explore the distant reaches of the solar system.

Think about the earliest Arctic and Antarctic explorers who braved the fierce climates on the planet's vast polar ice caps with little more than the stars in the sky and their hand-held compasses to guide them. No radio or GPS devices. None of our current technology.

The Great White Silence explores the history of one of those great treks across polar ice with film that is more than a century old. All one has to do is watch the following footage of the Terra Nova leaving Cardiff, Wales on June 15, 1910 to stand in awe of Captain Robert Falcon Scott's goal of being the first to reach the geographic South Pole.

On November 29, 1910, Scott's expedition set out from Port Chalmers, New Zealand on its ill-fated race to the South Pole. Joining Scott on board the Terra Nova was Herbert Ponting, who is credited with having filmed almost every aspect of the expedition.

While Ponting's footage of seals, Adélie penguins, dog teams, and ponies on ice will instantly charm viewers, the most important images he brought back were those he recorded of the preparations for the trek to the Pole (including trials of the caterpillar-track sledges as well as proper clothing and cooking equipment). In 1924, he re-edited his film and photos into The Great White Silence, using tinting and toning to make some scenes more vivid for viewers.

One of Herbert Ponting's tinted images of

the Terra Nova in Antarctica

As the official custodian of the expedition's negatives, the British Film Institute National Archive recently used modern photochemical and digital techniques to reintroduce Ponting's sophisticated use of color. The following video clip explains what the process entailed:

In the following video clip (which contains some great shots from the film), the British Film Institute's silent film curator, Bryony Dixon, and composer Simon Fisher Turner discuss how they went about creating a score for Ponting's film.

Simon Fisher Turner's score, however, was not the one performed in San Francisco in July. Following their acclaimed local debut at the 2010 San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Sweden's Mattie Bye and Kristian Holmgren were commissioned by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and the Headlands Center for the Arts to create a new score to accompany the Bay area screening of The Great White Silence.

It's hard to upstage such a riveting documentary, but the music they composed and performed not only honored Ponting's film, but immeasurably deepened its impact. For many, the Matti Bye Ensemble's performance was the highlight of the entire festival.

Although The Great White Silence was released on DVD by the British Film Institute in 1982, this newly restored print -- coupled with such thrilling music -- provided one of those unforgettable, other worldly experiences in silent film. Here's the trailer:

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape