The moon has been an object of wonder throughout human history. A glowing orb that shrinks to nothing and then comes back? In Buddhism, the moon is an enduring symbol of truth and enlightenment. For Zen painters (our focus here), it is also a model subject -- natural, versatile, and evocative.

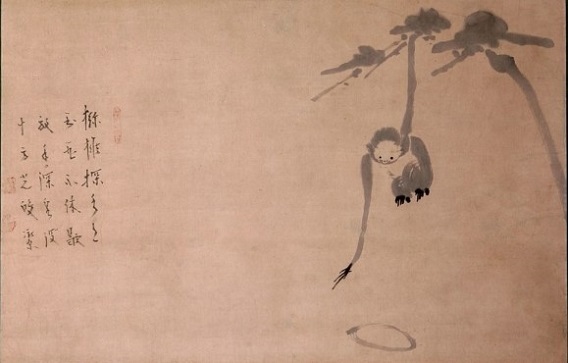

An unpretentious image by a Japanese monk provides a starting-point:

The scene may be hard to read at first. A monkey dangling from a branch is trying to grasp the moon reflected in the water below. The artist, Hakuin (1685-1769), is one of the most respected figures in Zen history, his art a mode of teaching. In this painting he depicts the monkey's quandary with just a few strokes. The moon's reflection is indistinct, the background empty. Only the monkey's eyes, feet, and hand are highlighted in black.

According to an analogy found throughout Buddhism, our true nature is hidden the way a cloud-covered moon is hidden. When the clouds disperse, everything is illuminated. The Buddha is sometimes called "the bright moon who illumines the world." In these contexts, moon usually implies a full moon, typically the full moon of autumn.

Misperceiving reality, the monkey fixates on an illusion. The reflection in the water (like everything else) depends on a constellation of conditions. The instant the moon sets, or other conditions change, the reflection will disappear. It has no independent existence. Still, we cling to the things we have and strain for the things we want. Suffering ensues. The Buddhist concept of delusion encompasses mistaken views, ignorance, self-deception, and mental illness.

Hakuin wrote extensively about his own struggles as a Zen monk. He knew how it felt to be stuck. Could his depiction of the monkey also be an acknowledgment of the difficulty of inner work? Does the monkey, however foolish, get points for persistence?

Here is another Zen painting that takes its cue from the moon:

This is a scroll by Fūgai (1568-1654), a Japanese monk inclined to solitude. The painting's protagonist is Hotei (Budai in Chinese), a legendary figure in Zen and East Asian culture. Wandering at will, Hotei was said to carry all his worldly possessions in a big sack.*

Hotei is pointing to the moon (as the inscription attests). His expression is so rapt, there is almost no need for him to point. Fūgai takes full advantage of the 'colors' of ink painting: light and dark strokes, open and closed spaces, and pale washes. The triangular composition rises, fittingly, to a point.

The central metaphor is well known: language about ultimate reality is like a finger pointing to the moon. Ultimate reality goes by many names in Zen -- Mind, Buddha, Buddha-nature, and so on. Hotei signals a goal, a direction, and, by extension, a path. But don't mistake the finger for the moon. Another analogy comes to mind: teaching a dog to fetch. The first time you throw something and point to it, the dog may mistakenly jump at your outstretched hand.

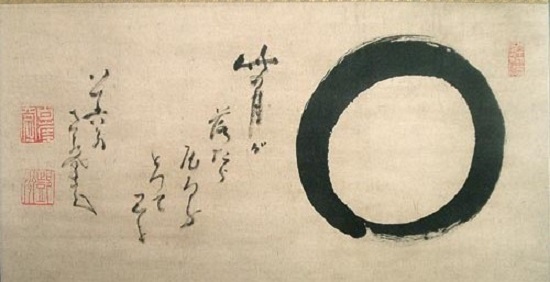

Whereas Hakuin's moon is reflected, and Hotei's is offstage, here is a moon in full:

The painter, Nantenbō (1839-1925), was an influential teacher who sought to preserve Zen's integrity during Japan's rapid westernizaton in the 19th century. With barely a nod to realism, this moon is vibrantly expressive. The feathery quality of the ink at the top and bottom contributes to a sense of motion. The image was made in a single stroke, starting from the lower left. Painting or calligraphy? Body and breath become brush.

Nantenbō identifies his image as a moon, yet other readings are not precluded. This is partly because Zen circles are a genre in their own right, called ensō. When a painting of the moon doubles as an ensō, the interpretive possibilities expand. A circle is whole yet empty, without beginning or end. So is the universe, in the Buddhist view. An ensō can also depict an everyday object such as a bowl (seen from above), a reminder that ordinary things are as ultimate as anything else.

The monkey looks down in confusion, Hotei looks up with conviction, and a full moon shines in all directions. In combination, the three images suggest a sequence. For example: delusion, practice, awakening. As a circle, the moon also introduces the possibility of circling back -- in this case, to Hakuin's monkey. Indeed, Zen maintains that Buddha-mind and monkey-mind have more in common than one would expect. Even amid delusion, there is awakening. Even amid awakening, there is delusion.

In this light, Nantenbō's inscription is a splendid response to Hakuin's monkey:

If you want the moon,

here it is.

Catch!

*On Hotei, see "Who Is the Laughing Buddha?"

Photo credits: 1) Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Canada; 2) Los Angeles County Museum of Art; 3) private collection.