The fundamental error most movie critics have made in their reviews of Baz Luhrmann's The Great Gatsby is the fact that they have critiqued the movie only against the so-called "great American novel" itself. Allow me to review Luhrmann's tour de force for what I believe it to be, which is a movie based on a movie based on a novel.

The context in which I recently viewed Luhrmann's Gatsby is key, having also just recently re-viewed Jack Clayton's 1974 The Great Gatsby, produced by David Merrick. I wanted to ensure I was not simply recalling the earlier film through time-dimmed, teen perspective as initially gathered when I first saw it as a seventh-grader. The 2013 version I approached as a casual Luhrmann fan, with not the highest of expectations, for one needs to be living under a rock to not be cognizant of its mixed-at-best reviews. I expected a sensory cacophony and accepted the near-endless cliches as Luhrmannesque. I get that Luhrmann's excessive layering of the colorful n trite is his directorial math, where the sum of the many parts is supposed to equal cinematic depth. As seen in the context of a story written to convey this very irony, I was not disappointed.

Post viewing Luhrmann's Gatsby, I read through other mass-market reviews, hoping some other critic would recognize the near verbatim rehashing of the earlier Gatsby as gleaned from the Francis Ford Coppola script, but I did not. Having so recently endured the'74 version, I recognized line after line from the Clayton rendition, placed not only phonically but also scenically and sequentially, moment for moment nearly identical to the Coppola script as to be almost predictable. Luhrmann's film felt to me like a glittery, trumped-up redo of its predecessor. At both Gatsby's introductory shindigs, the same gossipy quips flow in cadence with each other as cameras pan from one reveler to the next, matched down to the smeared, mascaraed eyes of the inebriated flappers. Carey Mulligan's Daisy is not quite as shallow or bland as was Mia Farrow's, but she speaks the same Fitzgerald snippets in the same fashion, in the same moments as did her forerunner. Sure, the novel is as light on dialogue as it is pedantic on Nick Carraway musings, so the options are a tad slim. It stands to reason we would hear lines echoed in both films, but the numerous similarities of word to blocking were too close to escape this critic's notice.

Not only is the dialogue in Luhrmann's version an ineffectual reworking of the '74 script rather than any attempt to create something fresh from the Fitzgerald opus, but so is the choice for Gatsby a copycat recasting of a big name, fair-haired Hollywood triple-A-lister. Leonard DiCaprio as Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby attempts to channel the box-jawed, blonde beauty as set forth by Redford, who at least carried off his sherbet colored wardrobe with as much aplomb as did DiCaprio. This first and last mistake both films' makers made, placing the greatest bankable actor in the greatest role for a film of the greatest American novel, rather than finding someone less "great" who might better embody the elusive character as prosaically suggested in Fitzgerald's writings. Both Gatsbys wound up being abysmally miscast, the first one looking like he would rather have been somewhere out west in a vest, the second who through mild physical humor (another Luhrmann signature trait) attempted to imbue his greatness with some bumbling affability and naiveté, perhaps more endearing than Redford's Gatsby but all the less convincing as someone who could rise to massive fortune in such a short time all by his little ol', sweet self. Any man who so rose in Prohibition-era, East Coast society will not have been quite so cute. Beyond that, we have the utter lack of chemistry between both Daisy-Jay combos, where the generic, even blonder beauty of the feminine lead did anything but engender some plausibility to Gatsby's long smoldering devotion. We are all still wondering what in the world the original Old Sport saw in his fickle, ordinary butterfly.

I noted also the major physical resemblance between the two George Wilsons, whose facial types and most especially eyes, wide set and pale, matched each other to a T more so than they manifested the marginally described Fitzgerald prototype. Notable is the fact that in the novella, it is George Wilson whom is ascribed the blonde tresses, not Gatsby. Not only that, Wilson's 2013 execution of Gatsby and even more so of self was a near verbatim match to its '74 precursor. Both Tom Buchanans were successful portrayals of moneyed dullards, Luhrmann's Joel Edgerton by far superior to Bruce Dern. Sam Waterston at least imbued his Nick Carraway with some grace, whereas Toby Maguire came across as little more than Jay Gatsby's romance lackey. Karen Black was as is Isla Fisher a casting of the pop-culture obvious, Black's singular gaze and creepy passion payed forward by Fisher, who did little more than reprise her zany Wedding Crasher ingenue as no doubt every male involved in the project insisted she do it. Fisher as Myrtle suggests a typecasting rut, however big the invite to play her was.

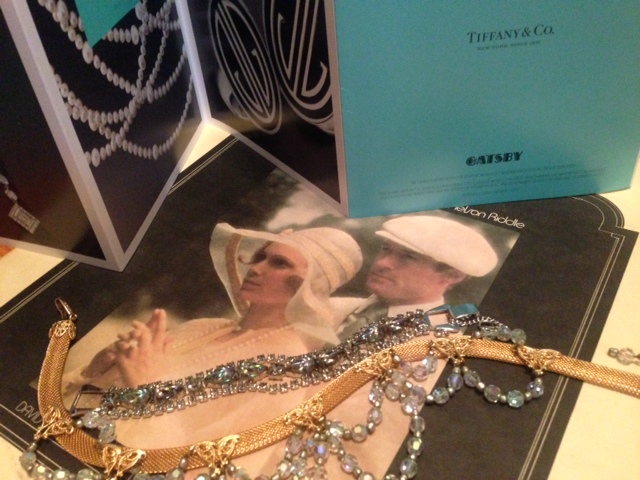

Luhrmann, in his study of excesses, falls short of any artistically delivered social statement in his over the top reliance on product placement as regards Prada, Tiffany and (so help me, even a label for those flying shirts) Brooks Brothers. It is difficult for anyone at any consumptive level to view these top-shelf designer brands as being representative of excess to the point of tawdry meaninglessness. The obvious nod to high brow bling and garb with the equally obvious as to be bland employment of executive producer's Jay-Z song bytes to sonically indicate anything off-lily-white in color (and yes I am talking racial commentary to entertainment crossover in hopes of snagging anyone under twenty-five, plus it does leave me wondering whose baby this project ever really was) and we are left with a 140+ minute commercial that can only be understood if one also knows it cost Luhrmann and company 100+ million dollars to fund this financial behemoth and that, in the spirit of gross over-consumption, they needed every last big name, every last dirty little penny. The Great Irony of Luhrmann's Great Gatsby is that, after all that money, most of us leave the theater not blown away but quantifying the experience (so long as one is not panning it) as merely pretty good, or just okay.

Far better an American study on the high cost of money and love is Martin Scorsese's cinematic masterpiece, Casino, whose 20th century Gatsby, Sam Rothstein is played by the brilliant if less-pretty-than-Redford Robert De Niro. De Niro's Rothstein, based on a real-life Vegas mogul, fights relentlessly to amass his fortunes and to buy and keep the love of a far more grotesque Daisy incarnate, the pathologically materialistic Ginger, the only role for which Sharon Stone was truly, commensurately lauded. "Money can't buy you love" is so profoundly imparted by Casino, I would suggest this movie if the moral is the story you seek.

Though it does a good job conveying the lethargy of vastly wealthy bores, Clayton's Gatsby feels more like a made-for-TV melodrama than any Oscar winning film. If it is a prime example of a'70s-retrofied, roaring twenties film you wish to see, then watch this Gatsby. You might find "What'll I do?" by Irving Berlin sticking with you longer than any of the movie's carefully crafted, soft-focus visuals.

If it is, however, a deep-dished, 21st century lasagna of layered cliche

Bucolic cottage and gardens that reek Thomas Kinkade, a gothic colossus that begs not for Daisy but for a "Rosebud!" instead, a Scarlet(A)-is-for-Adulteress-and-her-love lair (the Fragonard upholstery: oh, please) and a mansion with curtains cast as flailing ghosts so all will get that it is a haunted and unhappy place...

upon cliche

A catchall soundtrack that runs too much the gamut, from Phantom Opera staging to jazz to pop to hip hop to whatever...

upon cliche

3-D. The wacky driving scenes are completely compromised by it. Reckless driving is a key, recurring element in the book; in the film, it becomes nothing more than a visual sideshow. And those flapping curtains...

you wish to see, then I suggest you stick with the Luhrmann rendering of the Clayton rendering of the Fitzgerald work.

If Luhrmann's Gatsby inspires you to pick up a copy of the Fitzgerald novella and read it, and if reading The Great Gatsby leads you on to the discovery of other, far better classics than this worshipped bit of literature, then the movie will have, as the '74 version of Gatsby did for me, done its real work. Read, Old Sport.