As Sri Lanka marks six years since the end of a bloody war, looking at the country's post-war political realities through art

The post-war Sri Lanka witnessed "an unraveling of a political carnival, I was inspired by this, and the extravagance that it attempted to project. This collection captures this 'extravagance'" says Sri Lankan artist Gayan Prageeth, whom I met at Colombo's Saskia Fernando Gallery on a rainy Wednesday afternoon to talk about his latest collection of paintings, 'Extravagance'. The very use of the term 'carnival' instantly drew me into this conversation and I wanted to know more. And so we began to talk about some sensitive political realities Sri Lanka has been grappling within the post-war era. This article is based on this conversation, and expands into my personal analysis of the artist's collection.

The term carnival reminded me of the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin's famous "Carnival and Carnivalesque", a critique of the medieval carnival. Unlike medieval carnivals, which were literally celebratory gatherings that took place in public squares, Sri Lanka's very own political carnival was not exactly a carnival in its literal sense, but invites a satirical interpretation. This political carnival exposits the celebration, glamour, extravagance perpetrated through political maneuvering - through practices, norms, development agendas, and more severely through the careful conditioning of the public mind.

Bakhtin wrote that medieval carnivals created alternative social spaces, characterized by freedom, equality and abundance. The inception of Mahinda Rajapaksa regime, with the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka, was similarly a ritualised pageantry that made people believe in such deliverance. It was a brief escape from furrows [the war] and an enactment of utopian freedom and emancipation, with a defining feature of festivity and extravagance. Numerous victory songs played on the radio, flags raised in every street corner, and brilliant speeches made about democracy, accompanied by the taste of warm kiribath, and the celebratory burst of firecrackers were an indication of this festivity. These ideologically motivated festivities were followed by ambitious development projects. This political farce is not new to Sri Lanka, but a continuation or an evolution of an age old tradition.

Floating Rock, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 244 x 122cm

Gayan Prageeth's Floating Rock--a painting of an enormous boulder floating in the water like a dried gourd--demystifies the magnitude of the political carnival, great expectations which were raised, promises delivered, and the monolithic political vision of the former regime. The very fact that this boulder is floating indicates that even though it shows strength from the outside, it is hollow inside. It pretends to be something that it is not; its appearance is misleading.

To me, this painting captures the political grotesqueness, the incompleteness and the disruption of expectations. The grotesqueness epitomizes the accumulation of state power, militarization, ad-saturated democratic process, rights abuses, and colossal development projects such as harbors, airports, highways, luxury shopping arcades which displaced thousands of people. These projects have left us--as a country--mired in debt amounting to billions of dollars.

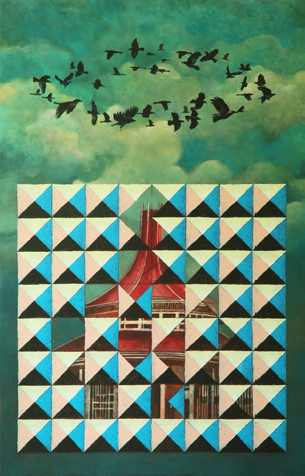

Diya-wanna?, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 122 x 145cm

The painting Diya-wanna? depicts the parliamentary building of Sri Lanka -- an architectural marvel which is Colombo's little showroom for democracy. Inside this architectural wonder are the representatives of the people - or so they are called - reducing this nationally significant building to a bear-pit as they sense blood, get to their feet or rock their chairs, shout, bray, laugh, stamp, point fingers at each other, and lose each other's voice in a bedlam. The flock of crows painted over the parliamentary building is symbolic of this.

To me, it also signifies the excessive powers wielded by hierarchical institutions such as the parliament and the high court [painting Court/Caught?] --a kind of power that seems proportionate against the greater 'evil of collapse' and things going out of control, in other terms people's revolt and critical consciousness. We have seen the erosion of justice and human rights owing to the atrocities of the State, military, and police. The mayhem that took place in Rathupaswala, where lives were claimed to silence the people who were demanding their basic right for clean drinking water is one such example; the autocratic impeachment of the chief justice is another.

In the two paintings, the colourful walls of boxes are an indication of how carefully this reality is being hidden from the public, through glossy media campaigns and charismatic speeches among other methods of maneuvering.

Court/Caught?, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 94 x 145cm

Climax, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 96.5 x 147.2cm

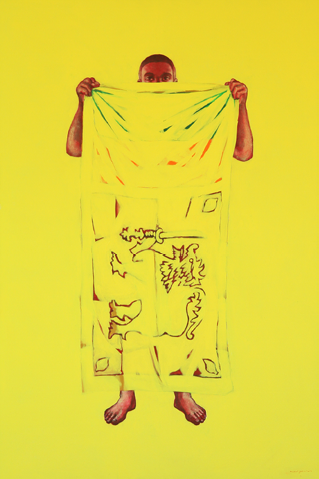

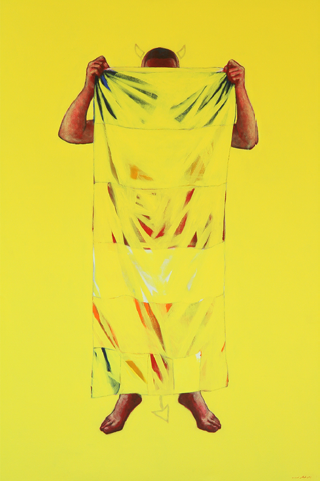

Gayan's paintings Climax, and What are you trying to hide? cleverly captures the surge of Sinhala Buddhist ethno-nationalism in post-war Sri Lanka and anti-Muslim hate campaigns gaining ground among the Sinhala population. In the recent past, we have witnessed campaigns against halal, attacks on mosques and Muslim businesses, spread of hate speech, intimidation and threats. The bloodshed that took place in Aluthgama is one such example.

Sri Lanka, as a country, has a history of periodic nationalist mobilisations, essentially due to the country's ethnocratic democracy which is ruled by the Sinhala majority.

The painting Climax is a portrayal of a young male attempting to hide his nakedness behind a heavy bouquet of blue water lilies - the national flower of Sri Lanka - which could be interpreted as metaphoric of overbearing nationalism, and shameless attempts to hide everything that is ugly behind patriotism and nationalism.

Also, blue water lily is symbolic to the previous regime; we have seen its overuse in political campaigns, on the television, on billboards - larger than life - in every street corner.

What are You Trying to Hide?, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 101.5 x 152.5cm

What are You Trying to Hide? I, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 101.5 x 152.5cm

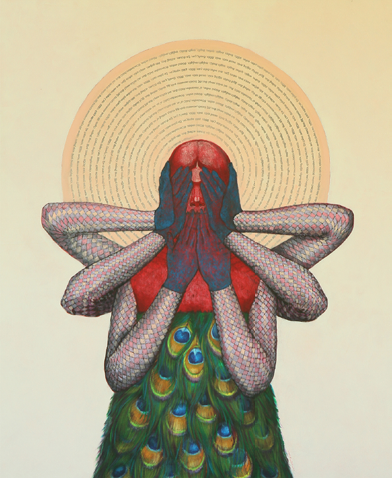

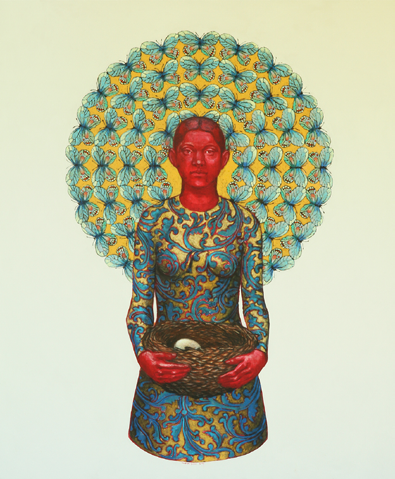

The Primrose Path II, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 125.5 x 145.5cm

The outpouring of Sinhala Buddhist nationalist tropes central to gender identity and roles such as 'good Sri Lankan woman', 'ideal Sinhalese woman' and 'good Buddhist woman' has been gaining momentum within post-war Sri Lanka. This stems from a familial ideology that has extended its tentacles through the State, political and administrative institutions, and powerful extremist organizations.

"The woman provides a solid foundation to the family as well as to society. She devotes her life to raise children, manage the family budget and ensure peace in the family..." - as stated in the election manifesto of former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, which was also the formal policy framework of the previous government.

With the previous regime coming into power, there was a momentous repudiation of the reproductive rights within the country. The ethno-nationalist ideology on the role of the Sinhala Buddhist woman prefigures her as the biological reproducer of the nation. Extremist Buddhist groups have been vocal about the supposedly diminishing Sinhala race and the need of--for want of a better term--greater propagation of the Sinhala race.

Such attacks launched on gender identity and roles by the ethno-nationalist project have been accepted and internalized by some sections of the general public, in some cases by women themselves. The continuing rise of violence of all forms against women and the demeaning treatment of female identity are the results of such mainstreamed and institutionalized prejudice.

Passion, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 122 x 145cm

The Pond of Dreams?, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 145cm

Gayan's "Pond of Dreams" is my personal favorite out of the collection. It captures much of the reality of Colombo's colossal beautification blueprint. The pond or the fish tank in this painting belongs to a glossy new shopping arcade, built by the previous regime, with every nook, cranny and corner breathing luxury in the middle of the Colombo city, with manicured lawns, water fountains, and floors paved with cobblestones. A citizen who contributed to a previous essay that I wrote about Colombo's beautification described this as "a development placebo, an attempt to cover up many other serious issues in the country".

This is an attempt to hide the beaten, banged and mutilated under layers of a sprawling city, to conceal the quiet menace of poverty that stains the city's glistening skyline. This space epitomizes the linear, monolithic, and militarized vision for development, creating prisons of consumerism, obliterating all connections with broader and much more important development issues, while instigating control and social polarization.

As cleverly captured by Gayan, the man in the painting resembles a citizen of the country, mesmerized by such beautification, comes from far away to watch, to observe. But little does he know about the burden of such luxury, such extravagance and such festivity. Everything about such spaces has a price tag on it.

To me, this man also signifies the hundreds of thousands of people who had their homes demolished and were driven out of their lands, so that city malls, luxury hotels, apartment complexes, and highways could take over their share of the land. These are the shadow people, who live in the cracks of neoliberal institutions and trickledown gentrification, whose basic rights to a land are snatched away from them. These are the people who are not even remotely included in any of these colossal and glossy development projects, and probably do not even realize the burden on their tax money. If you look closely at the painting, you will notice that the man has his eyes closed and hands tied, indicating that neither can he see nor touch, nor sense this political grotesqueness, nor can he change the system that has crushed his agency.

***

Mikhail Bakhtin writes that the central ritualistic act of the carnival is the false coronation and deposition of the carnival king. In January 2015, we the Sri Lankans, deposed one king and crowned ourselves as the citizens of the country, with all the colourful festivity - seemingly a demolition of hierarchal barriers, and losing of privileges of the authoritarians and the dominant discourse. As Bakhtin puts, it is "the world standing on its head", the world upside down. During the medieval times it was the clown, fool or the slave who were coronated, only to be shamefully deposed later. Similarly, one can be skeptical, that it is only a matter of time, within this 'political carnival', we the citizens realize that this is only a make belief, a temporary coronation, with no realistic basis to it - yet again a disruption of expectations. One can only hope that it wouldn't be the case...

The author wishes to thank artist Gayan Prageeth for an insightful interview, and Shanika Perera at Saskia Fernando Gallery for her support.

The pictures were obtained with the permission of the artist.