Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and the Federal Reserve's longest-serving top official reiterated their calls Thursday to rein in the nation's financial firms. But the two split on how they'd go about doing it.

In short, Geithner said he wants to give regulators more authority, leaving it up to them to exercise their best judgment. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City President Thomas Hoenig wants firm rules so the financial system doesn't have to rely solely on the wisdom of regulators.

During an appearance on Capitol Hill, Geithner acknowledged failures in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's supervision of Citigroup and other large banks, said regulators were "not conservative enough" when it came to overseeing banks' leverage ratios and criticized capital requirements as not having done a "good enough job" as a buffer against risk. Geithner pressed his case for why financial reform is needed now, mentioning the Obama administration's efforts to restrict leverage.

He also said that regulators like himself could have done more to prevent the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. "I do not believe we were powerless," Geithner said about his fellow regulators.

To ensure these kinds of failures are avoided in the future, Hoenig wants firm rules governing leverage and capital written into law. Geithner doesn't.

Like the pending financial reform bill in the Senate, Geithner wants to leave it up to federal regulators -- the same ones that presided over the housing bubble, oversaw extreme risk-taking by banks and other financial firms, and tried (yet failed) to contain a subprime crisis from mushrooming into a financial meltdown.

"I have spent more than 36 years at the Federal Reserve deeply involved in bank supervision, and it has been apparent to me for some time that our nation's financial institutions must have firm and easily understood leverage requirements," Hoenig said in prepared remarks Thursday before a House of Representatives subcommittee hearing. "Leverage tends to rise when the economy is strong as investors and lenders forget past mistakes and believe that prosperity will always continue. If we don't institute rules now to contain leverage, another crisis is inevitable."

Leverage refers to the use of debt to increase a firm's assets without a corresponding increase in capital.

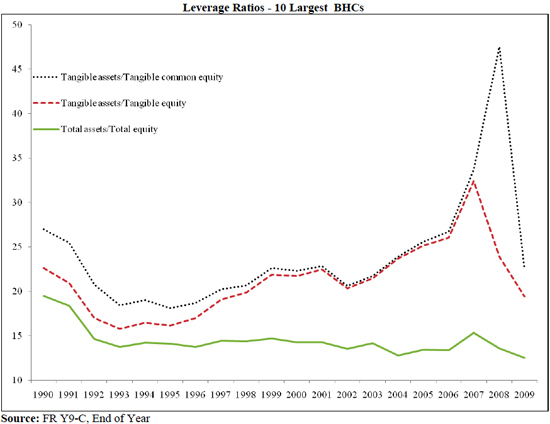

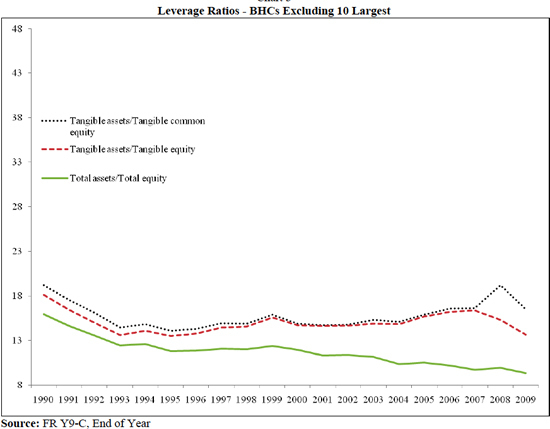

"The leverage at banking organizations has risen steadily since the mid-1990s, but was not immediately obvious because of the many different ways capital and leverage can be measured," Hoenig said. "In my judgment, the most fundamental measure of a financial institution's capital is to exclude intangible assets and preferred shares and focus only on tangible common equity -- that is ownership capital actually available to absorb losses and meet obligations.

"Looking at tangible common equity, you see that leverage for the entire banking industry rose from $16 of assets for each dollar of capital in 1993 to $25 for each dollar of capital in 2007. More striking perhaps, this aggregate ratio was driven most significantly by the 10 largest banking companies. At these firms, assets rose from 18 times capital to 34 over the same period, and that does not include their off-balance sheet activities.

"These numbers, in my opinion, reflect two essential points. First, that based on capital levels, the 10 largest banking organizations carried fundamentally riskier balance sheets at the start of this crisis than the industry as a whole. Second, their greater leverage reflects a significant funding cost advantage. Not only is debt cheaper than equity, but their debt was cheaper than for smaller organizations because creditors were confident these firms were too big to be allowed to fail.

"This was a gross distortion of the marketplace, providing these firms an advantage in making profits, enabling them to build size, and then, in the end, leaving others to suffer the pain of their collapse. This is not capitalism, but exploitation of an unearned advantage. And the list of victims is long, including families who lost homes, workers who lost jobs, and taxpayers who

were left to pay the tab."...

"The point is that institutions got away from the fundamental principles of sound management. And those institutions with the highest leverage suffered the most. Financial panic and economic havoc quickly followed. The process of deleveraging is underway, rebuilding capital has begun, but during this rebuilding loans are harder to get, which is impeding the economic recovery.

"With this very painful lesson fresh in our minds, now is the time to act.

"I strongly support establishing hard leverage rules that are simple, understandable and enforceable and that apply equally to all banking organizations that operate in the United States.

"As we saw in the years before the crisis, leverage tends to rise during economic expansions as past mistakes are forgotten, and pressure for growth and higher return on equity mounts.

"Straightforward leverage and underwriting rules require bankers to match increases in assets with increases in capital and prevent disputes with bank examiners over 'interpretations' of the rules.

"As a result, excess is constrained, and a countercyclical force is created that moderates booms and forms a cushion when the next recession occurs.

"I firmly believe that had such rules been in place, we would have been spared a good part of the tremendous hardship the American people have gone through during the past two years."

Geithner, on the other hand, said financial firms "need more requirements on leverage" during testimony before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, but didn't specify beyond that. He noted in his prepared remarks that regulators lacked proper authority to rein in financial firms' excessive risk-taking and inadequate capital levels.

However, regulators did have that authority -- they could have, on an individual basis, told firms to rein it in. The regulatory agencies could have issued rules compelling compliance. And all of these recommendations could have been backed up with credible threats allowed by law.

The problem, in hindsight, is that none of these tools were used effectively. Geithner was asked about that.

Heather Murren, a former Wall Street executive who now serves on the financial crisis panel, quizzed Geithner about the New York Fed's supervision of Citigroup. The commission on Thursday released internal Fed reports that criticized the New York Fed's supervision of large banks.

Geithner led the Fed from 2003 until his appointment as Treasury Secretary early last year.

Citing the internal reports, Murren noted that Geithner's New York Fed bank regulators had "insufficient resources" for "continuous supervision" of megabanks.

At one bank, which Murren identified as being Citigroup, the Fed examiners were inundated with tasks that kept "the team from fully completing its continuous supervision activities."

"The result is that there are insufficient resources to conduct continuous supervision activities in a consistent manner," the May 2005 report noted. "Not having sufficient staff to sustain continuous supervision activities on the...[team] may result in late reaction to address emerging risk areas within the [megabank's] portfolio."

Murren asked Geithner if he agreed with that assessment.

"I was very concerned in looking at our mix of responsibilities at those bank holding companies about the burden imposed by a range of what you might call compliance obligations -- consumer protection, CRA [Community Reinvestment Act], Bank Secrecy Act -- very important policy instruments... we were charged with enforcing through regulation, and the burden those imposed relative to the resources we had to also do... the more difficult tasks... [like] safety and soundness," Geithner said.

"I do not think we did enough as an institution with the authority we had to help contain the risks that ultimately emerged in that institution," Geithner admitted of the New York Fed's supervision over Citigroup.

Source: Thursday testimony of Thomas M. Hoenig, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

"Maybe part of it is about resources," he acknowledged. But a "more fundamental problem" was that regulators were "operating with a set of rules that did not compel firms to hold enough capital against the risks they were taking.

"That's why I believe it's so important in this reform process that we rely not so much on the discretion of supervisors to force more than the framework forces," Geithner added. Policymakers need to "try to get the rules better" so "you're not forced with the risk that these very capable [bank examiners]" are so heavily relied upon.

"You don't want the system to rely on their ability to force firms to be more conservative than the rules require," said Geithner.

Source: Thursday testimony of Thomas M. Hoenig, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

That's why Hoenig wants firm rules in law. Yet while the Treasury Secretary said "[t]he proposed reforms will require the enforcement of more conservative capital and leverage requirements on the activities, whether on or off balance sheet, of all major financial institutions," that's not something new -- regulators could have done it all along. And the main Senate legislation, authored by Senate Banking Committee Chairman Christopher Dodd (D-Conn.), does not specify the degree to which regulators will be forced to up their standards.

"I strongly support establishing hard leverage rules that are simple, understandable and

enforceable and that apply equally to all banks and bank holding companies that operate in the United States," Hoenig said Thursday.

"For an example of the power of a hard leverage rule, consider the impact on assets and/or equity of restricting bank holding companies to holding no more than $15 of tangible assets for every $1 of tangible equity capital.

"As I noted, at the end of 2007, the 10 largest bank holding companies held $34 of tangible assets for every $1 of tangible equity capital. If the maximum leverage ratio was 15:1, these companies would have had to reduce their assets by $4.9 trillion (56 percent), increase their tangible common equity by $326 billion (125 percent), or some combination of the two," Hoenig said.

An amendment to Dodd's bill sponsored by Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) and Ted Kaufman (D-Del.) that would have capped leverage ratios at about 16-to-1 failed Thursday night. Twenty-seven Democrats, including Dodd, voted against it.

READ the Fed's 2005 internal report on the New York Fed:

READ the Fed's 2009 internal report on the New York Fed: