--William Bouguereau,The Bacchante

For reasons no one seems able to explain, France of late has been deluged with graphic images of the bacchanal. In case you've forgotten the bacchanal is not merely a wild sex frolic in the woods. It was the mythic sylvan orgy that led men, women, beasts and children into hysteric ecstasy wherein the heroic well-muscled lads inevitably fell victim to the deadly magic hidden behind irresistible, large breasted nymphs.

Obsession with the bacchanal has swept the western world on a regular basis since the Renaissance brought light to the grim, gray Middle Ages. Bacchanal obsession reached its height among painters and sculptors at the height of the prudish Victorian era. Now in this era of ISIS, evangelical End Days and environmental melt down, the mysteries of the bacchanal are back, and Bacchus's bowl is overflowing.

I might have been fifteen when I first learned about Bacchus. The Flowing Bowl was the title of my father's weekly column at the Yale Daily News, over the signature Dionysus, columns that his strict Methodist father surely never read. Dionysus, or for the Romans Bacchus, was, like Jesus, the mortal human born from the thigh of Zeus, placed here to celebrate and encourage the delights of sensuality--and to encourage madness among the witless.

This year's extraordinary display, Modern Bacchanals: Nudity, Inebriation and Dance at the Galerie des Beaux Arts in Bordeaux, is at once visually sumptuous and strikingly encyclopedic. It also addresses directly today's global eruptions and disruptions over the meaning of gender. It brings to mind centuries of Bacchanalian parades throughout the Italian boot, festivities led by women that repeatedly brought the Republic to quaking danger.

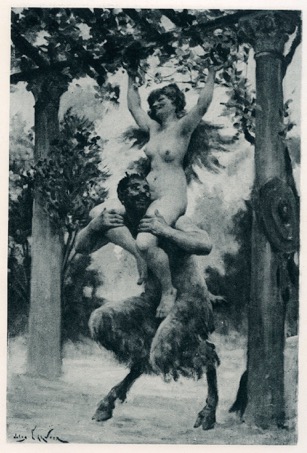

--Armand Sylvestre, gravure of Rabelais's Nude

As one contemporary commentator wrote "they have been celebrated all over Italy and

now even within the City in many places, and [...] you have learned this not only from rumour but also from their din and cries at night, which echo throughout the

City, but I feel sure that you do not know what this thing is. Some believe that it is a form of worship of the gods, others that it is an allowable play and pastime, and, what ever it is, that it concerns only a few ... First, then, a great part of them are women, and they are the source of this mischief; then there are men very like the women, debauched and debauchers, fanatical, with senses dulled by wakefulness, wine, noise and shouts at night."

The observer might have been an early 20th century journalist, but in fact it was the Roman author Livy writing in 186 BC.

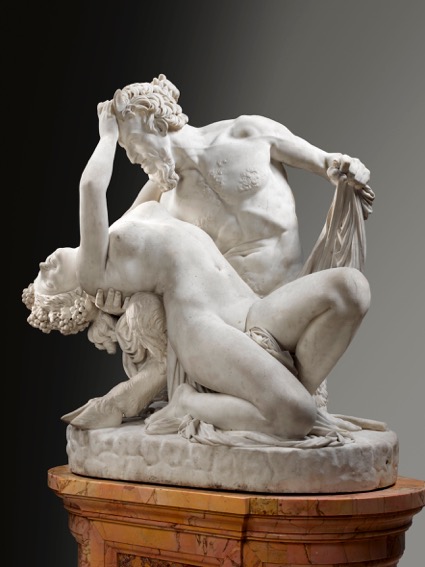

The myths of the bacchanal, as well as their periodic re-enactments, have particularly fascinated artists especially during the height of industrialization in the 19th century, which is the focal period of the paintings and sculptors at Bordeaux: Rodin, Renoir, Courbet, Delacroix, Lévy, Gérome and notably the sculptor James (Jean-Jacques) Pradier. All of them and scores more are present in this collection, which run until late May.

"There was a great fascination [then] with the relation between love and wine, particularly represented by Bacchus," curator Sandra Buratti-Hasan explained. At the same time 19th century French artists fell under a near obsession with the bodies of women, specifically the voluptuous--and profoundly dangerous--figure of the bacchant, the seductive figure whose animal powers are repeatedly revealed in her ecstatic coitus with the horned, bearded half-human, half-ram Satyrs. "They are free in their bodies, they are free in their sexuality: it's around that, their power that fascinated, and frightened, the men."

Emile Levy, The Death of Orpheus

Nowhere is that fear and obsession clearer than in the scores of paintings and the many operas drawn on the myths of the ill-fated lovers Orpheus and Euridice. The myths are manifold, but at the core is the question of whether Orpheus, the son of the god Apollo, was true in his love for his lost Euridice. In the version that most captured 19th century artists the wild female Maenads distrusted the irresistibly handsome Orpheus whose talent at the lute had drawn everyone to his charm; in their crazed wine-fueled hysteria, the Maenads pierced Orpheus with a spear.

At the core of the bacchanal lay the notion that female power once released led to hysteria beyond male control spreading chaos across the land. Fear of female magic is as ancient as the Greeks and as contemporary as Jihadist rape and evangelical damnation. And of course more sophisticated notions of female hysteria played a key role in the darker side of Freudian and post-Freudian psychoanalysis.

instability.

--Edgard Maxence, The Fawn

The paintings, the gravures and the sculptors in the Bacchanale Moderne require little explanation once these classical references are born in mind. Still, one of the most remarkable absences in Western art's celebration of the voluptuous female body is how devoid those bodies were of actual sex organs. Before Courbet's notorious Origin of the World women's sex was almost always completely erased: no labia, no clitoris, and only very, very rarely the slightest suggestion of a vaginal crease. For all their love of Bacchanal debauchery, the same is true for these 19th Century painters and sculptors even as well-formed testicles and penises are on full display, not to mention tight muscular buns on the male backsides.

This persistent erasure of female sex--as opposed the well developed male obsession for bulging mammaries and pert nipples--was until the arrival of 1960s feminism an unmistakable hallmark of occidental art. Not until the new kinds of bacchanalia represented by Woodstock and its imitators, would the mysteries beneath Courbet's pubic forest come into its own.

--Jean-Jacques Pradier, The Satyr and the Bacchante

[All images courtesy Bordeaux Musée des Beaux Arts]

NEXT UP: A retrospective of Judy Chicago's Vaginal Dinner Party in paint and porcelain.

Coming in June From Bloomsbury