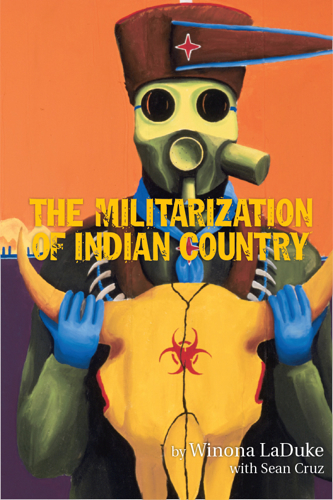

Image courtesy of Honor the Earth

Winona LaDuke, a Native American activist and twice Ralph Nader's Green Party Vice Presidential Candidate , has written a dramatic and prescient book, The Militarization of Indian Country (Honor the Earth). Completed in February 2011, the book is currently at press and comes on the heels of the capture and killing of Osama bin Laden, also known as "Geronimo EKIA" (Enemy Killed in Action). When the code name for bin Laden was revealed, Native American groups sat up and took notice. Harlyn Geronimo, a great grandson of the legendary Apache chief, asked Congress for a formal apology.

As a member of the Mescalero Apache Nation, Geronimo is an Army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam. In a statement submitted to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Geronimo demanded, "That this use of the name Geronimo" be expunged "from all the records of the U.S. government;" adding "to equate Geronimo with Osama bin Laden is an unpardonable slander of Native America and its most famous leader in history."

Which brings us to the timely publication of LaDuke's book. In it she uses considerable scholarly prowess to examine how and why Native culture has become inextricably entwined with military institutions. Consider that the names the military uses for operations and weapons come straight from Native nomenclature. In recent war accounts, the American media wrote vividly about the use of "Apache Longbow" and "Black Hawk" helicopters as "Tomahawk" missiles rained from the sky in the Gulf and Middle East Wars. Soldiers who burn out in the battlefield in a foreign land "go off the reservation." The implication is that they flee to Indian land.

In a transcript of an interview with Amy Goodman of "Democracy Now," LaDuke charges this terminology and the use of the code name "Geronimo" for bin Laden represent "the continuation of the wars against indigenous people."

Those who disagree might say that LaDuke is relying upon "political correctness" to make her point, but read the book and what emerges goes straight to the heart and soul of the militarization of not just Indian culture, but mainstream American ethos as well.

We visited with LaDuke at Minnesota's White Earth Reservation, where she lives, and asked her to elaborate on the military's use of Native terminology in the bin Laden affair.

I understand why they did it, he (Bin Laden) was expensive to fight, he was elusive, and he was smart. He had far more political support than Geronimo. Obviously Pakistan liked him. The problem with the use of the code word, "Geronimo" shows a lack of the historical understanding of using the name of such a national hero, and not just to native people. Geronimo is also a national hero to Americans. In this case it is an insult. The book illustrates how the military has always been above reproach.

The Militarization of Indian Country examines in dreadful detail how the military has poisoned, murdered, and exterminated parts of indigenous populations. It is carefully organized into sections examining the deep ties between the military and indigenous people, how the economy drives the military and vice-versa, the military's appropriation of Indian lands, and a somewhat hopeful prognosis for future relations if America rethinks her priorities.

In this well-researched, critical, and historical analysis, LaDuke at times takes the stance of a spiritual teacher, redefining and correcting the common interpretation of what it means to be a "warrior." LaDuke uses both a scholarly and soulful process; reclaiming the breadth and depth of Native spirituality on behalf of her people, and giving the reader concise insight into a belief and honor system that is unique in its interpretation of war, its responsibilities, and its consequences.

She writes:

I do not hate the military. I do despise militarization and its impacts on men, women, children, and the land. The chilling facts are that the US is the largest purveyor of weapons in the world, and that billions of people have no land, food, and often, limbs, because of the military funded by my tax dollars.

LaDuke begins her narrative at the Fort Sill army post in Lawton, Oklahoma, where she says the Skull and Bones society of Yale is still accused of "grave robbing, exhuming, stealing and then desecrating the bones of Goyathlay, or Geronimo, the great Apache chief." Today, the Comanche nation is asking for an agreement that the military not destroy the sacred site of Medicine Bluff.

"A small request, it would seem, at the only active military installation still remaining from the Indian Wars of the 1800s, and at the largest artillery range in the world," LaDuke writes.

"Ogichidaa is an Ojibwe word that loosely translates as 'warrior,'" LaDuke says, but the nuance imparts a deeper meaning as "those who defend the people" when used in the plural. Words and language are important and too often misinterpreted or bastardized so as to completely lose the original significance.

The words of the great chief Sitting Bull are a good example; words that LaDuke uses to drive this message home. She quotes Sitting Bull as he explained the responsibilities and the mind-set of the native warrior.

For us, warriors are not what you think of as warriors. The warrior is not someone who fights, because no one has the right to take another's life. The warrior, for us, is one who sacrifices himself for the good of others. His task is to take care of the elderly, the defenseless, those who cannot provide for themselves and above all, the children, the future of humanity.

LaDuke challenges the reader to grasp the disconnect inherent in the stereotype of Indian warriors as "bloodthirsty killers." "There are critical differences, however, between a war fought to defend the people and the land, and a war fought to create or sustain an empire, to impose colonial rule on an unwilling population," LaDuke says.

In this context one can truly understand Native people's revulsion of the word "Geronimo" when used to identify the murderous bin laden. It is especially fascinating that LaDuke wrote The Militarization of Indian Country before the current controversy arose. Truth is universal and does not adhere to convenient historical timelines.

In LaDuke's narrative, the broken treaties, poisoned waters, rivers of tears, forced death marches and massacres such as the one at Wounded Knee serve to riddle the reader with guilt. It is not the guilt of immediate responsibility, but guilt that comes from realizing that ignorance breeds culpability. The Seventh Cavalry, the same unit that conducted the "Shock and Awe" campaign in Iraq, inflicted the atrocities at Wounded Knee. To ignore historical precedent is to acquiesce and condone future atrocity. The reader realizes that obliviousness is no excuse.

There is a difference between the ancient customs of tribal warfare designed to keep enemies at bay and warfare "designed to kill en-mass," LaDuke says.

Winona LaDuke in Interview at White Earth Reservation © G. Nienaber

"I'm up for a fight. If you gotta fight, fight," LaDuke said in our interview at White Earth. "But you must look at the expenditure and the fact that the majority of people killed in war are non-combatants, and that the military is the largest purveyor of weapons."

In her book, LaDuke writes "more than four fifths of the people killed in war have been civilians. Globally there are some 16 million refugees from war."

The facts are undeniable and irrefutable. From Alaska to Los Alamos, to the Hawaiian island of Kaho'olawe, and every inch of American soil in between, the assault on indigenous life has been vicious and complete. The holy Hawaiian island was used as a bombing range, destroying sacred shrines and actually cracking the aquifer before Congress placed a moratorium on the bombing.

The Militarization of Indian Country also charges that the U.S. military is the largest polluter in the world.

From the thousands of nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific that started in the 1940s, obliterating atolls and spreading radioactive contamination throughout the ocean, to the Vietnam War-era use of napalm and Agent Orange to defoliate and poison vast swaths of Vietnam, to the widespread use of depleted uranium and chemical weaponry since that time, the role of the U.S. military in contaminating the planet cannot be overstated.

Indigenous people have certainly experienced the brunt of the exposure. LaDuke tells the story of Virginia Sanchez, a Shoshone woman who grew up downwind and in the shadows of the Nevada atomic bomb testing site. Her brother died of Leukemia at 36 and she has lost many other relatives to cancer. Her testimony is powerful and riveting.

When the nuclear tests were exploded, in school we would duck and cover under the desk, not really understanding what it was. We weren't wealthy, you know our structures weren't airtight.

Seventy miles southwest of Salt Lake City a small community of Goshutes live on an 18,600 reservation where the U.S. government has "created, tested and dumped toxic military wastes all around them," LaDuke writes. Not 10 miles away, at the Dugway Proving Grounds, the federal government conducts military tests of chemical and biological weapons.

In the 1990s, documents were declassified regarding an Arctic experiment conducted on native populations without their knowledge. The village of Point Hope was irradiated so that the military could study the bioaccumulation of radiation in caribou. No one told the people.

LaDuke provides many more examples of how the military has been intimately entwined with the destruction of Indian land and culture, and this analysis could be compared to a forced marriage based upon systematic rape.

Which brings us back to Geronimo (Enemy Killed In Action).

Despite all of the atrocity perpetrated upon them, Native people remain at high rates of enlistment in the U.S. military, and have the most living veterans of any community. Of the 42,000 who served in Vietnam, 90 percent volunteered.

"These people deserve respect," LaDuke rightly says.

The reality, as LaDuke told Amy Goodman, is that "Geronimo was a true patriot, his battles were in defense of his land, and he was a hero. The coupling of his name with the most vilified enemy of America in this millennium is dangerous ground. "

Probably the best testimonial to LaDuke and her critical thinking comes from Cornel Pewewardy, D.Ed. His heritage is Comanche and Kiowa, and he is a Director and Professor of Indigenous Nations Studies at Portland State University.

The Militarization of Indian Country reflects a resurgence of the classic warrior perspective in the great spiritual traditions of Indigenous warriors. While "The Art of War" is unmatched in its Taoism principles... (this is) a book about Winona LaDuke's love for the Warriors of Peace -- Indigenous ways of understanding the roots of racism, violence, conflict, resolution and reconciliation.

At White Earth, LaDuke told us that while she was "humbled" by Pewewardy's tribute, her main reason for writing The Militarization of Indian Country was to repay a "debt" she felt she owed her father. Vincent Eugene LaDuke (Sun Bear) was a conscientious objector to serving in the Korean War. He spent 11 months in prison for his beliefs.

LaDuke credits Portland editor Sean Cruz with providing valuable research and editing skills.

For more information and to order advance copies of The Militarization of Indian Country, please contact Honor The Earth at info@honorearth.org.