By now, you probably know who Michael Sam is. The University of Missouri football star is on track to become the first openly gay NFL player this spring. You definitely know who Ellen DeGeneres is -- the first major television star to come out. Movie buffs have no trouble explaining who Harvey Milk is. The first openly gay politician was portrayed with theatrical aplomb by Sean Penn in the eponymous movie.

But if we asked you to name the first openly gay member of Congress, could you? Members of older generations may. But younger people -- including more than a dozen political operatives we tested -- could not. Perhaps that's because this story of coming out was so shrouded in scandal, so drenched in professional embarrassment, that its broader significance may forever be overshadowed.

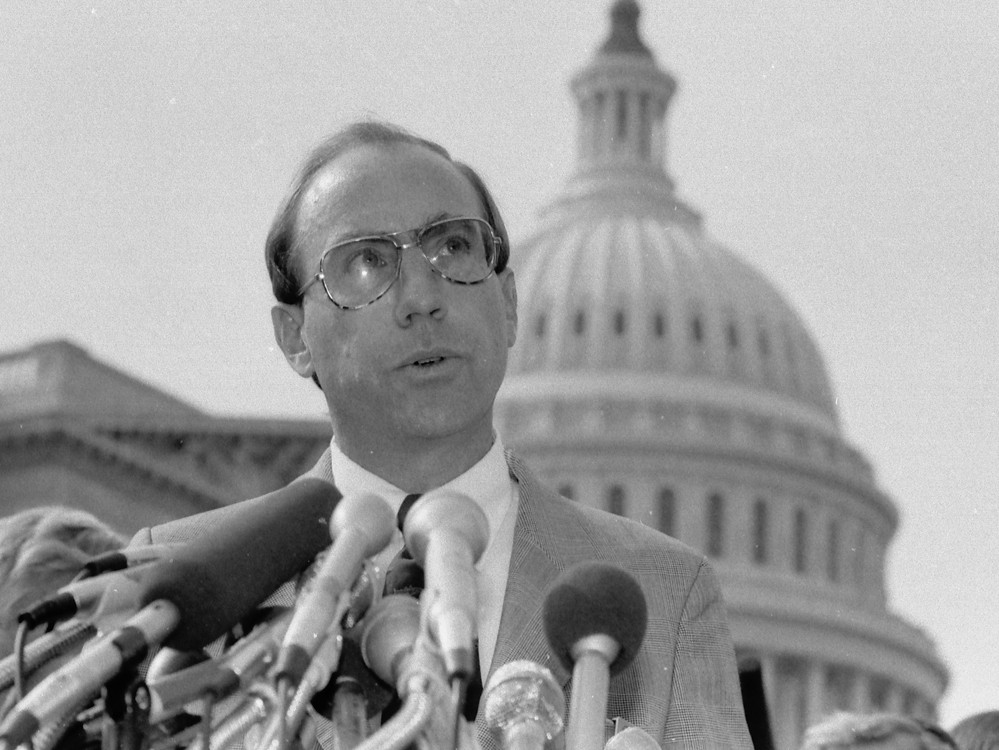

This is the legacy of Gerry Studds, the long-serving Massachusetts Democrat who was, for those who followed his lead, every bit the historical figure as the first gay athlete, movie star and politician, but is best known as the congressman censured by his own colleagues in 1983 for a sexual relationship with a 17-year-old male congressional page.

"I think that people in politics and especially people like me who are in politics and lived through that will remember him as being a real hero, because he was willing to be first," said Richard Socarides, a longtime Democratic operative who served as an adviser to President Bill Clinton for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues. "Even though he was forced into it a little bit by circumstances, I think that people think of him as a hero and someone we look up to and someone who was a trailblazer."

Looking back at Studds' story three decades later, Socarides and others marvel at the circumstances that surrounded it. Certainly, the congressman was chiefly responsible for the drama -- he admitted missteps, though insisted that his relationship with the page was consensual. But the turbulence that accompanied his coming out seems more like a relic of the past. Part of the reason Michael Sam's highly controlled outing portends a smooth breaking of NFL barriers, they argue, is because Studds forged the way.

"The single biggest reason why we have seen this erosion of homophobia very rapidly is because people have come out," said former Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), a onetime colleague of Studds who announced that he was gay years later. "The reality has eroded the prejudice."

Studds was not an unknown backbencher when it was revealed that he was gay. He had a long political lineage, played a prominent role on Eugene McCarthy's 1968 presidential campaign and was first elected to Congress in 1972.

His trajectory was disrupted in the summer of 1982, when two former congressional pages went to House leaders and charged that lawmakers had engaged in sexual relationships with members of the youth-volunteer program several years earlier. A yearlong investigation by the House Ethics Committee revealed that Studds and Rep. Dan Crane (R-Ill.) had been involved.

Crane had been caught with a 17-year-old female page. In Studds’ case, the report said he had invited a male page to his Georgetown home, plied him with vodka and told him he was too drunk to drive him back. The report also said that Studds took the page on a two-week trip to Portugal (which the congressman did not pay for with taxpayer funds). Notably, the report quoted the page saying that their relationship was consensual. With the age of consent in D.C. being 16, it was also legal.

Read The Full Ethics Report Below

The committee recommended that the two members be reprimanded for the relationships. But some of their House colleagues wanted to go further. A formal censure would, in the words of then-Rep. Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.), "repair the integrity of the United States House of Representatives."

Studds disputed the report's conclusions, but waived his right to a public hearing, saying he wanted to protect the identity of the page. As the censure motion was read and passed by a vote of 420 to 3, he turned his back on the House members, facing the speaker. The New York Times' report from that day, July 20, 1983, describes his demeanor as "grim but stoic." Video of the vote does not appear to have survived.

Hilary Rosen, a Democratic strategist and longtime LGBT rights advocate, was standing just off the House floor that day as the vote transpired. She had gone to the Capitol building to be there in support.

“He was extremely self-conscious. He was embarrassed and he was pissed,” Rosen said. “He was angry that this was kind of the way that this was all playing out.”

After the vote, Studds walked out of the chamber and fielded a mob of reporters, according to a passage from Studds' unpublished memoir provided to HuffPost by Dean Hara, Studds' husband.

"With only a few cameras to dodge and duck, I hurried down the stairs and into the car. As we went, new cameras materialized, and the car had to nearly run them over to get out of there," Studds wrote. "From the Capitol we drove directly to a friend’s house where we watched the evening news. I called my mother, had a few drinks, and then I went to bed. I didn't sleep very well that night."

Studds was not the first member of Congress to be caught in a gay relationship. Not even the first that decade. Just a few years earlier, Rep. Jon Hinson (R-Miss.) announced that he had been arrested for exposing himself to an undercover police officer at the Iwo Jima memorial in Arlington, Va. Hinson also disclosed that he had survived a fire that killed nine people at a Washington theater that catered to gay clientele. But he denied that he was gay, blamed alcoholism for his troubles, and won reelection. A year later, he was forced to resign after being arrested in a House office building men's room, where he was caught giving oral sex to a male employee of the Library of Congress. It was only after he left office that Hinson acknowledged his sexuality.

In another scandal around that same time, Rep. Bob Bauman (R-Md.) was arrested for soliciting sex from a 16-year-old male prostitute. The arrest, during his 1980 reelection campaign, resulted in his loss to Democrat Roy Dyson, who stood little chance of winning prior to the controversy. Bauman went on to write a book detailing his closeted gay life, called The Gentleman from Maryland.

Unlike Hinson and Bauman, Studds chose to not dispute his outing, and stood a chance of holding onto his seat after it. He had been stripped of his committee chairmanship -- a huge blow for any member, but particularly for Studds, who used his top post on the House merchant marine subcommittee to secure projects for his district. His standing was diminished enough that a Democratic primary challenger ran against him on the premise that he'd be better in a general election against a moralizing Republican. But Studds fended off the primary and won reelection with 55.7 percent of the vote.

It was significantly less than the 68.7 percent he had earned in 1982. But it was enough to set history. He not only would be the first openly gay member of Congress, he’d be the first one to win an election.

Sensibilities in the early 1980s were hardly kind toward the LGBT community. The AIDS crisis was starting to take hold, and conservatives like Pat Buchanan, who served as President Ronald Reagan’s communications director, were chalking up the epidemic as “nature’s revenge on gay men.” As Studds emerged from his page scandal and reelection, he confronted a political world that lacked the institutional structure or basic awareness to support an openly gay member of Congress.

“Back then, there weren't any gay people,” said Mark Forest, a former top aide to Studds, speaking figuratively. “You had to think about it in that setting. For Gerry, it was like, 'Wow, a gay person? What's that all about?'”

In the meantime, Studds got back to work. He focused heavily on maritime issues, but didn't shy away from national politics, criticizing the Reagan administration for subterfuge in Central America. He also talked about topics of concern to the gay and lesbian communities. In May 1987, he called for the surgeon general's report on the AIDS epidemic to be mailed to everyone in the country. For his part, he pledged to mail it to each household in his congressional district.

There was hate mail from constituents enraged about his sexuality. But being outed, he insisted, had been more liberating than isolating.

"If there are any members who have difficulty dealing with me, it is not directly or indirectly, subtly or otherwise, apparent to me," Studds said, according to a Nov. 11, 1985, Associated Press article. "On the contrary, I would say there is more ease."

Video Of Studds Discussing Gay Rights Advancements In 1987

Victor Basile, a longtime friend to Studds and the first executive director of the Human Rights Campaign, said he and Studds would travel the country in the mid-'80s as Studds gave speeches to various gay communities. Basile said the congressman provided solace to LGBT people struggling to live openly. Studds, too, seemed grateful to talk about those struggles, he said. "It was a voice that found a lot of resonance among the community at a badly needed time,” Basile said. “He'd obviously been in a lot of pain for a long time, being gay and closeted, and I think he felt the need to be out."

Privately, Studds suddenly found himself the wise sage on gay politics. Barney Frank, his colleague from Massachusetts, talked to him routinely about his own process of coming out. Frank had put it off -- first when he was elected to Congress, later when Studds was outed.

"At the time, I represented the district next to him," Frank recalled. "We were friendly. We knew each other was gay. I'd been thinking about coming out myself, but when this happened to him, I figured I better wait. We represented extending districts in southeastern Massachusetts. It was just too hard in the twin cities, you know."

But the reaction to Studds provided a measure of relief. Frank recalled how people in the district "became protective of Gerry." The average American "was less homophobic than he thought."

When a book was about to be released that heavily insinuated Frank's sexuality, he told then-House Speaker Tip O'Neill (D-Mass.) the truth. In 1987, Frank became the most prominent politician to voluntarily out himself.

"Gerry was the first to say [when caught], 'Yes I did it and yes I'm gay and it's tough being gay and this is how it happened.'" Frank said. "Three years later -- I didn't want to do it in the next election cycle -- but he frankly gave me the go-ahead as far as I could see."

For all his years in Congress -- the public speeches and glad-handing with voters -- people close to Studds said he found the business of politics stifling. People interviewed for this article described him as “introverted” and “guarded,” and were divided on whether he would have come out on his own if the scandal hadn’t forced him. Most agreed that he was a reluctant leader for the gay rights movement.

“He did all the Human Rights Campaign things, but I was never sure he was happy doing them," said Basile. "The times we were together, he was clearly not in a good mood about it." It was when he would go on stage to give a speech, Basile continued, that a switch would flip and he became a different person.

"He was an incredibly gifted orator. Very funny, very thought-provoking," Basile said. "There have been very few people I've seen who could speak with his ability. It was really quite amazing.”

Toward the end of his career in Congress, Studds became more outspoken. He had been appointed chair of the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries in 1990 and met his future husband Dean Hara in 1991. In his final years in office, he became a forceful proponent for LGBT rights. One of the few videos of him that exists on YouTube stems from a speech he gave to the PFLAG [Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays] convention in 1993. In it, he recounted an encounter with a Bible-holding constituent who asked if he was still a "practicing homosexual."

"I said, 'No, as a matter of fact. I think I'm very good at it,’" Studds replied. The crowd ate it up.

A more poignant, reflective moment came a year later, during an interview with the website Annoy.com.

"This whole struggle of ours is the final chapter, major chapter certainly, in the struggle for civil rights, which is so much of the history of America," Studds said. “But we don't know where we are in that chapter. My guess is we are fairly early in that chapter. That may be the bad news. The good news is that we know that chapter will have a happy ending. We know that this, like all the other chapters in that long struggle, will end victorious. We really will overcome."

The remark was offered about the same time as the military issued its Don't Ask Don't Tell policy. Two years later, in 1996, came another setback, when President Clinton signed the Defense of Marriage Act into law, codifying the non-recognition of same-sex marriages. Months after that, Studds retired from Congress and became a lobbyist for the maritime industry.

He wedded Hara in 2004, after Massachusetts legalized same-sex marriage. But when he died on Oct. 14, 2006, he was unable to pass along his congressional pension because of federal prohibition. The last, victorious chapter that he envisioned in 1994 wouldn't come in his lifetime.

Few people today think of Studds as a pioneer for the LGBT movement. His indiscretions certainly played a role in preventing that. In fact, you're far more likely to see his name on a list of congressional scandals than among the trailblazers.

"I think that there was a lament about the circumstances, and I think that Gerry felt ashamed of it," said Rosen. "He felt apologetic and felt badly that that's what happened. In later years, he acknowledged that. He was also an extremely proud man. A little defiant."

But Studds' timing also was a factor. The political community had to be jarred by the gay rights movement before it could be moved to support it. And Studds' outing did the jarring.

"I think that quite early on, the gay rights movement realized that these stories had a reaching impact on people's perceptions," said Socarides. "The movement, broadly speaking, invested in developing strategies for this and best practices for this, and what to do and what not do. Certainly none of that existed before Gerry Studds. He actually helped us write this playbook."

Today, LGBT political institutions are more robust and politically sophisticated. Voluntary outings, like that of Michael Sams, are handled with intense care and comprehensive media strategies. An entire LGBT infrastructure exists to advance causes in the courts and in Congress. Studds' widow is part of it. Last year, Hara signed on as a plaintiff challenging the constitutionality of DOMA before the Supreme Court.

And he won. The court ruled the law had unfairly denied federal benefits to gay couples legally married in their states, which entitled Hara to the benefits he was denied when Studds' died in 2006.

“I'm actually astonished at how far we've come in such a short period of time,” said Basile, Studds' friend. “My regret is that the people I was in the trenches with didn't live to see it."

This article was updated to include new details about the day Gerry Studds was censured in the House of Representatives.