This is the third installment in the series, The 3D-Materialization of Art, an ongoing survey tracing the new and growing movement of highly-reflexive 3D spectacle and narrative art and activism. Made by artists who distance themselves from the commercial uses of 3D in motion pictures, television, advertising and gaming, the new 3D artists employ the same technology that the commercial industries use. The difference is the 3D-materialization artists extend the dematerializing values and strategies of Conceptual Art to digital imaging, narratives, mythopoetics, satires and paradigms that promote progressive and sustainable political, cultural and natural lifestyles for the present and future. The other Huffington Post features in the series include commentaries and criticisms on the 3D art of Claudia Hart, Matthew Weinstein, Jonathan Monaghan and the bitforms gallery exhibition, Post Pictures: A New Generation of Pictorial Structuralists A related article includes the digital art of Morehshin Allahyari in a particularly global feminist context.

CORE-IB2012-4min from Kurt Hentschläger on Vimeo.

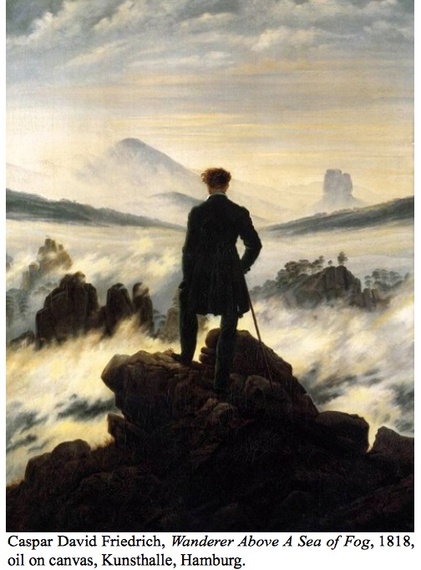

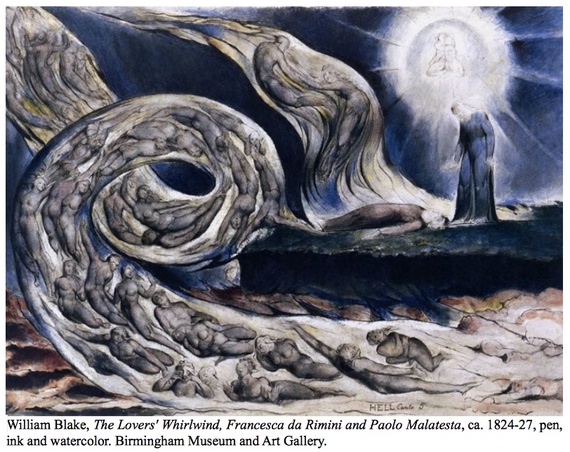

With two November 2013 installations opening the same day -- one at the Paris Nemo Festival and one at the United Arab Emirates' Sharjah Art Foundation -- the reputation of Kurt Hentschlaeger, the Austrian new media visionary now based in Chicago, continues to expand globally. For two decades, Hentschlaeger has been pushing international audiences toward newly-traced boundaries between the synthetic and the natural phenomena alluded to too often and too vaguely as the sublime. Although conventionally called an audio-visual artist, the nomenclature is inadequate for a polysensory maestro who, along with Pierre Huyghe, Ryoji Ikeda, and Olafur Eliasson, is to the installation art of the new millennial generation what Caspar David Friederich and William Blake were to the Romantic movement in 18th and 19th-century painting -- a frontiersman of sensory augmentation.

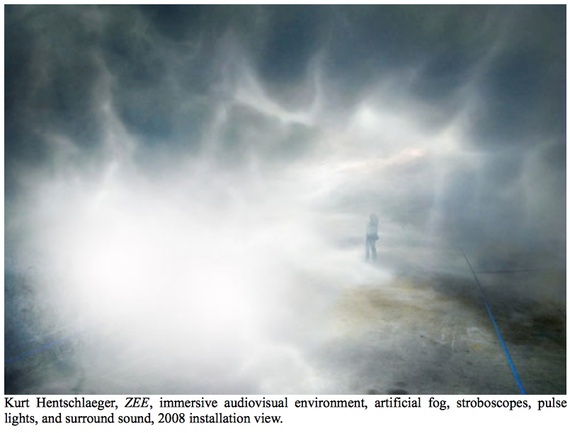

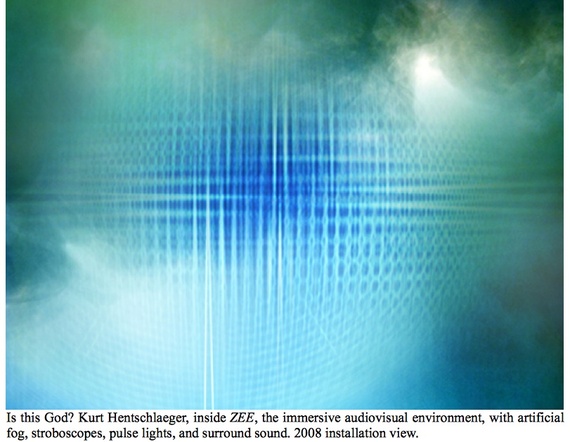

But whereas the Romantics saw themselves as ushering audiences to the precipice from which transcendental realms of ecstatic and spiritual rapture could be accessed, Hentschlaeger introduces audiences -- or more accurately, his performative-participants of our more materialist and pragmatic age -- to a full array of physical/virtual experiences conceived of as continuous and unbounded phenomenological infinitudes. Hentschlaeger is currently touring ZEE, a spatial-theatrical installation that is both audience-performative and experiential as a full touch-sense immersion into synthetic mists rhythmically timed to strobes of light. Besides Paris and Sharjah, ZEE has enveloped audiences at the Museum of New and Old Art at Hobart, Tasmania, Australia; the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (Fact), in Liverpool; the Laboratorio Arte Alameda, Mexico City; the File Festival, São Paulo; the Wave Exhibition, INDAF, Seoul; the Wood Street Galleries, Pittsburgh; and FuturePerfect, in New York.

The universality of Hentschaeger's media language accounts for his popularity throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East, as the language of his sensory-environmental installations in particular are both sub-linguistic and sub-semiotic. By this I mean the artist synthesizes an experiential primordiality that heightens our awareness to a devolutionary state of awareness before sight was made the primary, directive sense of animal existence, along with our own, all-too-human distraction from our less-developed, external senses for touch, taste and smell.

Not that the participants in Hentschlaeger's immersive installations have their vision entirely closed off. Upon entering the synthetic mists of his bounded environment, ZEE, sight is merely diminished in capacity so that touch, and to a lesser extent the senses of smell and taste, and even sensation of our internal organs and their vital functions (pulse, pressure. breath, perspiration, temperature) are heightened to a ratio equivalent with sight and hearing. For some participants the heightening is so precipitously disorienting that Hentschlaeger has to issue warnings about the dangers to entrants prone to seizures. It's not rare that people have to be escorted out of his womb-like returns, though more often because of the anxiety that so intimates an awareness with one's own body than any physical danger. Less frequently, the strobes trigger epileptic seizures in participants suffering from photosensitivity.

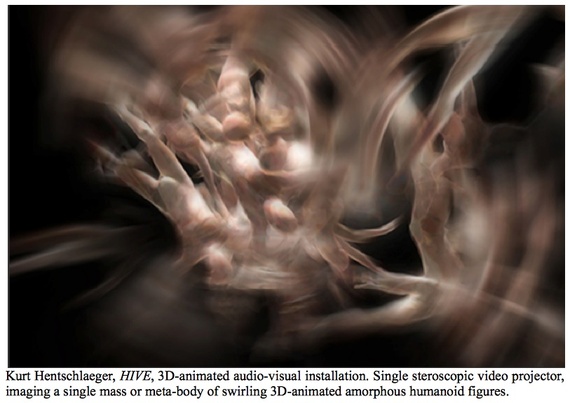

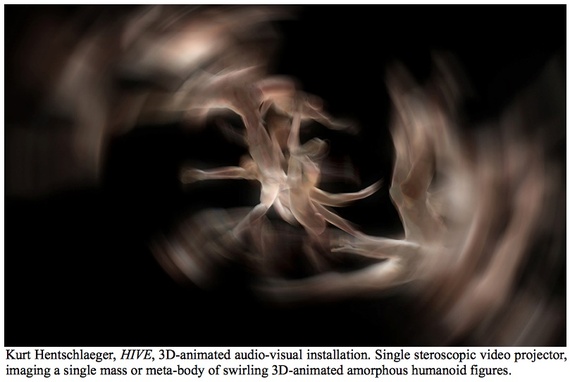

Hentschlaeger is also circulating a corpus of 3D animation video installations that boldly convert old-age mytho-metaphysical models of a transmigratory "ectoplasmic" variety of life force at the edge of some virtual-electromagnetic spectrum. Throughout 2012, Hentschlaeger's CORE, a 3D animation, five-channel video projection installation, was shown in the London 2012 Festival coinciding with the Summer Olympics, where it startled and captivated audiences both for its bold spectacle of virtual fantasia and its metaphysical implications as a commentary on human behavior. After having blackened a cavernous 19th-century engine shop at the Ironbridge George Museum in Shropshire, England -- a historical preservation site renowned as one of the earliest centers of the Industrial Revolution -- Hentschlaeger projected a quintet of videos depicting large-scale "swarms" of virtual, faceless humanoid drones engaged in an enthralling hive-like flight -- one weightlessly synchronized as a ballet of perpetual convergence and dispersal. Instead of evoking the spectral souls of wishful faiths and myths, Hentschlaeger's humanoid swarm mindlessly scatters and converges in formation as if the figures collectively, yet intricately, demarcate a living, breathing universe -- perhaps the kind imaginably endowed as an anthropomorphic prime mover or force. In this, the clustering movement of the collective is more evocative of a school of fish, flock of birds or herd of animals, impelled by a common instinct or constraint, than a race of Homo Sapiens imbued with free will.

The effect of seeing an aerial choreography virtually performed by a cluster of human forms so devoid of individualism and choice is at the same time rapturous and profoundly disturbing for its suggestion of a perpetual afterlife or eternal utopia outside space-time and premised on absolute submission and subjugation. When considered against the real historical backdrop of 19th-century capitalist industrialization and consumerism specific to Ironbridge, the work pointedly takes on moral and political implications in its modeling of a single-purposed communality analogous to human worker drones sustaining a dangerously totalitarian or oligarchical power.

CORE is the culmination of a body of 3D virtual video projections the artist has shown since 2000 in such settings as The Venice Biennale, The National Art Museum of China in Beijing, The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, PS1-Clocktower in New York, and The Society for Arts and Technology in Montreal. In 2010, Hentschlaeger also received the prestigious QWARTZ Electronic Music Award in Paris. I asked Hentschlaeger to summarize what he'd intended to convey with the provocative virtual imagery of clustering bodies.

"I think the clustering-bodies body of work can be described analogously as unconscious bodies in a kind of Neverland, in-between state. There is a body of work now with four individual pieces: CLUSTER, which is a single screen live show, projected improvisationally (with me on hand controllers) that dates from 2010-2012. Then there is HIVE, which is a stereoscopic, single-screen installation from 2011. CORE, at Ironbridge, is my 2012 "symphonic" installation with five individual groups on five separate screens, each consisting of 23 bodies in projection format. And there is MATTER, a site specific composition for the new dome at the Society for Arts and Technology in Montreal, which opened May 30, 2012. I plan to do one other piece, called KOMA, with several screens and groups of bodies, in a surround setup, each group with a smaller number of bodies, rather than the 23 bodies that CORE features per screen."

CORE is essentially a work about unconsciousness in ways confrontational with the most basic and blatant audience presumptions concerning spirituality and mysticism. It's possible to see in CORE the same devotional reach for exalted human nature that William Blake sought in his search for the divine. It's an association that, in fact, Hentschlaeger encourages with the work's 2012 installment in Ironbridge, an English town that has preserved its Victorian legacy and ties to the romantic movement of which Blake was a part. Conversely, what can be described as a depiction of a single-minded attraction to a central magnetic and radiant force seems in accord with the definition some mystics and faithful have for spirituality as a letting go of all personal will and desire in a submission to a higher being and purpose.

CORE's audience was largely on hand to see the Summer Olympics, and as such Hentschlaeger found them to be comprised of greater diversity than the crowds who descend on the Venice Biennale, Documenta, and all the many international art biennials. The difference here is substantial: the great majority of people drawn to the Olympics or to Ironbridge's history weren't art-world-savvy, and thereby the issue of spiritual interpretation had the potential of becoming a thorny thicket. But Hentschlaeger, who doesn't personally subscribe to religion or spiritualism, anticipated this in his initial conceptualization of CORE.

"Spirituality is a problematic label," he told me. "I'm a nonbeliever in ideas of deities and higher powers. Reflecting on mysticism comes more easily, or at least the aspects of it that relate to states of consciousness -- aspects of reality, beyond normal human perception. The limits and malleability of human perception is one of my key areas of interest and extends to ideas of what can and can't be perceived and whether the unknown can be understood more than just as a concept, and beyond that can render anything but imaginary constructs, such as belief-based systems. In regards to my pseudo physics-driven work with virtual bodies, when I say that they are 'unconscious,' even this is misleading in that they have really no consciousness whatsoever as mere ephemeral constructs without ego, will, desire, emotions."

"Then again," he goes on, "being an art creation, they are informed by my own existence, ideas and will. And most of these ideas orbit around issues of technologically-induced fantasies of omni-control and omnipotence. So these floating bodies are initially empty vessels, free of ego and also individuality, particles rather than beings. It's just by their humanoid form and motion that we connect to them and project onto them subjectively. But also, the way that they move and cluster together in virtual zero gravity invokes historical references to angels, disembodied spirits, drifting souls, etc."

Hentschlaeger then brought the discussion back to the structures that underpin all his work: "Coming back to our contemporary obsession with control, functioning, managing, structuring, compartmentalizing, and the consequentially-inflicted orgy of material possessions (or in popular neurological terms-the dominance of left brain hemisphere processing), I find our civilization's craving for infinite comfort and control (of life inside and outside of ourselves) futile and ultimately prone to leading to the opposite of our desires. We are all being controlled by our drives and desires. I'm not advocating a dystopian model here, but rather am interested in a 'hyper-civilization' based on a historical process of emancipation from ancient belief systems. On the one end, it does engage the mystical 'complex' to connect to the larger unknown outside of oneself and transcending one's own prison of body and ego, while on the other side it still subscribes to rational thought and thus acknowledges the obvious duality of being both a discrete quasi-autonomous being as well as a particle within a mass. I have to add that, as a consequence of being 'ideologically non-committal,' the prototypical connoisseur of the romantic sublime tends to stay in a safe, albeit non-ironic distance, and thus very much remains locked into a position of observing rather than participating in the dangers of life."

The seed for Hentschlaeger's "floating body" oeuvre was planted when he designed a modest projection video and set design for the Paris Ballet Preljocajas. Commisioned by the company's choreographer, Angelin Preljocaj, the dance was called N, the simple letter that is the abbreviation for 'haine', the french word for hate. The dance enacts "hell on earth", according to Hentschlaeger, meaning "what happens when we lose control over our bodies." In accord with this theme, Hentschlaeger's first figurative animation paired real dancers with virtual bodies. In fact it was through the choreography that Hentschlaeger had come to know of the impetus for his future animated projections, and fittingly. For as any dancer can tell us, choreography demands that dancers submit to the designs of a tyrannical overseer, not succumb to a freer improvisation from within.

It was a new experience for Hentschlaeger to work with dancers, but not with human bodies. Throughout the 1990s, Hentschlaeger recorded and projected real human subjects representing a range of psychological and perceptual conditions that heighten our perception of the dehumanizing effects of media on modern life. With N, Hentschlaeger came back to representing bodies, but now they are virtual bodies, animations. The special effects of animation allow the artist to manipulate virtual bodies in ways not afforded to him by real living subjects photographed. In so doing, Hentschlaeger learned how the forces that he analogizes theatrically, in real life impact upon real bodies, while pushing, accelerating, intensifying the desired effects on these bodies in ways unacceptable in interactions with real subjects.

Hentschlaeger also has a media source for the floating bodies oeuvre. "In the research informing N," he told me, "I looked into computer game engines, which are the realtime animation software backbones of any computer game. I was particularly interested in shooter games and war simulators, for both their viscerally entertaining simulations of combat and killing, and for their banal brutality and mass slaughtering of virtual opponents from the comfort of one's chair. The plan was to use the realtime of such software as a model for interacting intuitively with a choreographer and dancers and to build on the virtual physics algorithms employed to create a more lifelike simulation of human motion."

"Unreal Tournament, the game engine I based my first floating bodies generation on, had one outstanding micro feature that caught my attention. On the death of 'a combatant', the body sinks to the ground, starts convulsing, jerking, and then dissolving into particles to instantly spawn a virtual reincarnation. It is upon having been killed in the game that I found the moment of 'losing control,' whereby the convulsing body drifts off, to be the only body that seems truly human and touching in an otherwise redundant, superficial world."

This convulsing, out-of-control body resurfaced unintentionally, and with "a spooky twist", a few years after, when, in one of Hentschlaeger's early immersive works using strobes and fog, the strobes triggered a participant's epileptic seizures due to his photosensitivity to light. In this sense, the loss of control was as much existentially forced on Hentschlaeger as it was an intended and continuous thread of both his figurative projection videos and his immersive environments, ZEE, where particpants must slowly feel their way through a thick mist. "When we find ourselves amid the synthetic mist and strobes of ZEE, we have the experience of losing all reference points perceptually, almost physically. I say almost physically because we retain the experience of feeling the floor beneath us, and the awareness of our own bodies, but little if anything else. We can't see or hear anything of substance. And then, there are those visitors who lose even these physical references and have to be ushered out of ZEE."

Whereas the immersive work imposes a substantial loss of perceptual and physical control, the projected virtual domain presents an analogical loss of control that tells us about art's propensity to reaffirm experience rather than to challenge it. Hentschlaeger admits that his fascination with the loss of control trauma links to a primal narcissistic injury inflicted on us despite all the insights, knowledge, efforts, accomplishments of our technologically-addicted civilization. "There is no way out of the basic human trajectory which always ends in our demise. I stick with my suspicion, that most of our technological obsession orbits around our desire for heightened control of our lives, specifically through attaining stability, longevity, and ultimately the promise of transcending (read: continuing) our destiny on this planet rather than in whatever mythological scenarios beyond."

"My life from early on was rich in death. When I was eight years old, my father died. Until I passed my father's age of death, I had no doubt that I wouldn't live long, and in hindsight I often behaved accordingly. I collected a fair share of near-death experiences on an almost regular basis during my twenties and thirties, some of which I still can't quite grasp why I survived them. In my feeling of living on the 'edge of a precipice,' I acutely remember feeling things being washed out of my hands, finding myself as much in an observer's position as struggling for a way out."

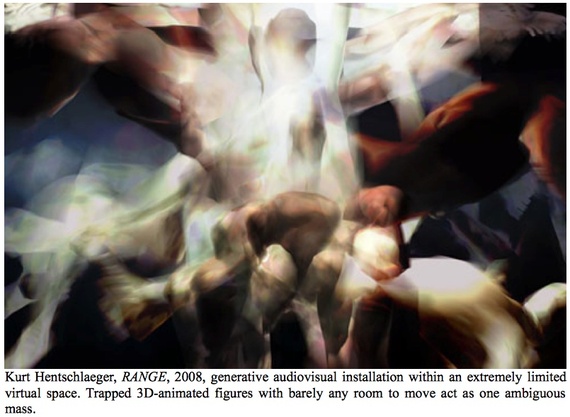

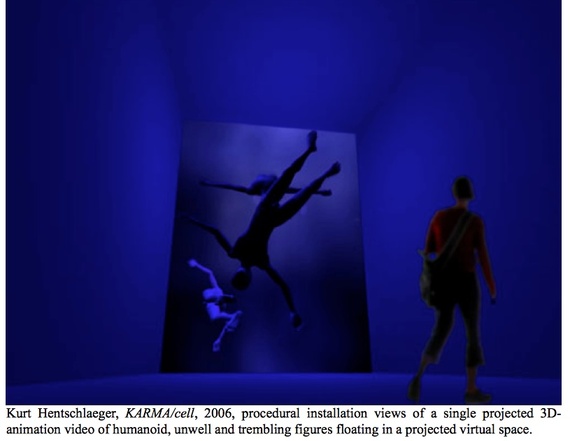

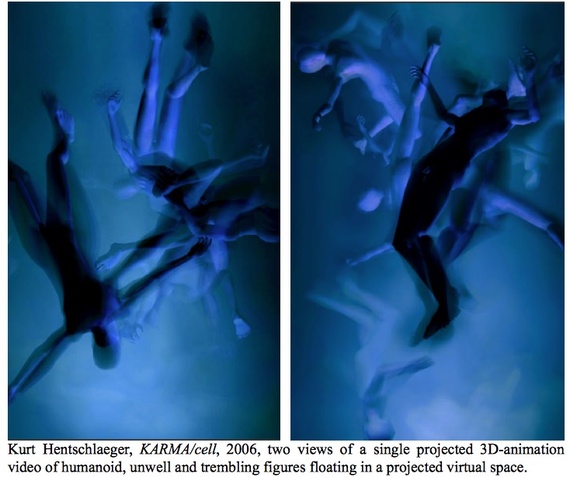

"All of this informs my early virtual bodies installations KARMA and FEED. For these, I developed virtual bodies that not only move and navigate entirely through convulsions, but also define the range of possible motions and aesthetics of the work. The result is a staged virtual black box lit by strobing virtual lights. The lights help us to visualize a zero gravity void in which a number of identical clone bodies seemingly interact without recognizing their respective body boundaries when they drift through each other like ghosts."

"After N, from KARMA and FEED on, each virtual body doubles as a sound instrument, creating and shaping sound through motion and changes in position in the zero gravity space. The greater the quantity of virtual bodies in the environment, the more complexly and richly the droning sound builds, creating a synchronized audio-visual impression."

"In 2008, I started a massive overhaul of the animation platform, having reached the limits of the Unreal software. The now finished instrument is allowing for more complexity as I move away from convulsions to focus on a more realistic interaction between individual bodies, swarm behavior, motion patterns, and an overall impression of ephemerality. CORE, the latest, most nuanced and symphonic work in the series, is realized with this platform. It is exceedingly more dynamic in both motion patterns and audio-visual rendering than my earlier works. Like CLUSTER, HIVE, and MATTER, from within the same work group, they are concerned with virtual embodiment of the fleeting, the immaterial, and the aether beyond matter."

The wide media range Hentschlaeger explores brings us to the issue of the audience's interaction with different media and their conventional genres. This is something artists have been doing on a grand scale in an art context since the Fluxus artists of the 1960s (and on a more modest scale since Dada), when kinetics, light, sound, music, performance, film, video, and audience participation extended the parameters of cultural experience. But with the advent of the digital New Media in the last twenty years, the component of audience interactivity--or what the New Media guru Lev Manovich calls The Myth of Interactivity -- has become the subject of scrutiny for being too vaguely conceptualized by artists and critics. And so there has been a push to further articulate the different interactive structures used in the new media object and experience. The trouble is, as Manovich has made much of, it is difficult to theoretically define and describe the user experience of interactive structures and the objects and images that facilitate them. Furthermore, the New Media artists' adoption of conventional media languages -- those of painting, sculpture, writing, theater, and cinema -- are then transposed by those artists insufficiently to digital productions.

"There is a terminological confusion here," Hentschlaeger warns, "as most works tagged as 'interactive' should be rightfully labeled as 'reactive,' which points to a much more simple and rather mechanical process. What I'm saying is that I see interactivity as a complex, intelligent process, something alive, with a good amount of unpredictability and not necessarily an end or set time-space frame. This is what also makes any auratic art work interesting and truly interactive, in that it will trigger a personal response in the viewer, and for that matter as many possibly different responses as there are people in the audience. The response is not even limited to the time spent with the artwork, but can linger in memory and can color lives going forward, as with other intense experiences."

"Of course, the classic art-viewer interaction disallows feedback on, or changes to, the artwork. The beauty of this model is that compelling art is both radiant and static-hermetic. The viewer isn't expected to overtly, physically or dramatically interact with the art work, but enter a solemn, inner and often quite meditative process, in which the artwork, if attractive enough, is quietly devoured and fed into one's fabric of cultural experiences. I agree with Lev Manovich about The Myth of Interactivity, but I doubt that active user participation any day soon will evolve into something as meaningful as what we already have -- and that is a passive viewer/user participation. 'Interactivity' in media art comes with the Myth of Technology, the eternal promise of improving on nature. Short of true artificial intelligence, I don't see how enough intelligent complexity could be rendered to create truly interactive, rather than classically reactive work. We are a conscious, intelligent, sensual and emotional species and tend to get bored quickly because of that nature. To occupy our interest for a longer period of time, objects and processes are required to be challenging, ambiguous, enigmatic, and mysterious, if not mystical -- everything but mechanically predictable."

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.