Firstly, let me say that I have written about this topic before - hence the 2.0. Regardless, it is still the number one question I get asked, "How did you publish your photography? What can I do to get my work published?" There no simple answer to these questions. However, there are a number of things you can do, and a few things you shouldn't do, that are worth pointing out.

Do you have a project worth publishing? This is perhaps the most important first step. Answer this question not only with honesty, but with the input of others, ideally a professional editor. You would be surprised at the number of "press-ready" projects I see that are, if anything, absolutely not ready for publication. Publishing a book of photography has to be more than merely making a photo album and then sending it out into the world. The narrative needs to be tight, there needs to be a story. You also need to make sure the work is well edited. If your project contains two hundred images, you should aim to publish around fifty or sixty, not the entire two hundred. Photographers often drown out their good work in a sea of "okay" work. This is a very common mistake. Be selective and edit without mercy, then, do it again! Also, like I said, seek help. Portfolio reviews are one of the best ways to do this. Many photographers, including myself, offer portfolio reviews for peers and friends. It's not me saying I know more than you, it's me saying as a fellow photographer - a peer - allow me to review you work and provide you with a sober second opinion. Shelve the ego from the very beginning or you will never make it to press!

Next, I highly recommend making a mockup book. Use a self-publishing service like Blurb or Lulu and make a book which represents, as closely as possible, what it is that you want the actual publisher to produce. Publishers will be able to actually see what you are proposing, rather than simply a pile of photos. This process may also help you to see what it is you have and whether or not you feel it is the right moment to press ahead with the work.

Consider your proposal from an outsiders point of view. Are you known as a photographer? If not, what makes you feel your work would be of interest to anyone, especially at a cost? Publishers are not into stroking egos, so you will have to find something about your work which is unique and attractive from a business point of view. Remember, presses, even small ones, are in for a profit. Even "nonprofit" presses frown upon publishing books which are nothing more than a colossal expense. If you've never been published in magazines, or exhibited in galleries, chances are your project will be a hard sell to a traditional publisher. Rather than chasing this impossible dream, I recommend spending more time entering contests and submitting to magazines and galleries to try and build a better resume prior to approaching a book-length project. There are also other alternatives too.

Artist books are a great alternative. That is, produce the book yourself. Self-publishing is not to be discounted. It's true that there is still some stigma attached to this route in the literary word, but that is not the case with art and photography. Photographers have been publishing their own work from the very beginning. Famous photographers like Martin Parr have been at this for decades with great success. Because the books are more objets d'art, and less books, they usually accumulate higher value. Some of Parr's out-of-print books sell for hundreds if not thousands of dollars. Because you are in control, and are usually producing in small numbers, you can produce books which are of a higher quality. Milk Books is a great service for this option. Produce in a limited number and hand-sign and number your books. This method has often been more successful and profitable for many photographers anyway.

Whatever you do, don't simply mass mail your book project out to every press you can find on the internet. This is a waste of time, money (in the case of mockups) and you will likely also annoy editors and publishers, who will not be so quick to forget your name. Be careful, your career will hopefully be long and successful. Just because Taschen doesn't want to publish your book today, doesn't mean they won't want it a decade later. As is the case with everyone, they save databases of correspondence, if you tell them off now, you may regret it later on. Be smart. Submit appropriate mockups that are truly ready for publication to selective presses. If you get several rejections this is not an indication that presses are evil and you should teach them a nasty lesson in a hastily written email, it is rather an indication that likely your work is not ready for book form.

I asked my own publisher to weigh in with his thoughts on this process. Here's what Joe Pan, publisher at Brooklyn Arts Press, had to say:

"Style in photography is elusive, meaning it's incredibly difficult for a photographer to develop a style that doesn't come off as a direct emulation of a more well-established photographer. Plus, we've been overexposed to images our whole life, so finding true unique qualities in photography is rare. That said, when someone is capturing something in a way that works on a deeper level, it leaves you breathless. That's the mark, when it hits you like the perfect haiku, bewilderment borne somehow from the common. You can deconstruct a photo a hundred ways, yet you can't deconstruct so easily presence of mind, or the architecture of urgency, or a gaze's natural empathy, each of which any person standing in front of a photograph for the first time can experience without being told what to expect. When looking over photography books for BAP, we look for these indescribable qualities made present. The biggest mistake, honestly, is people thinking they're ready for a book when they aren't. Or misunderstanding how images in close proximity are speaking to each other, or purposefully clashing, or aren't speaking at all. In terms of what MUST be present: vision."

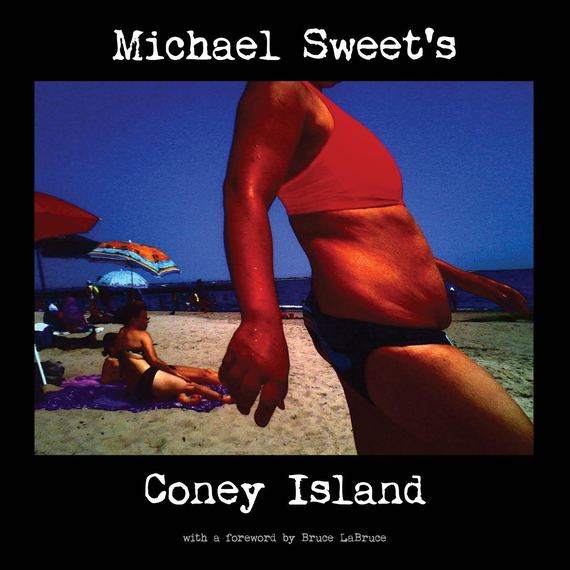

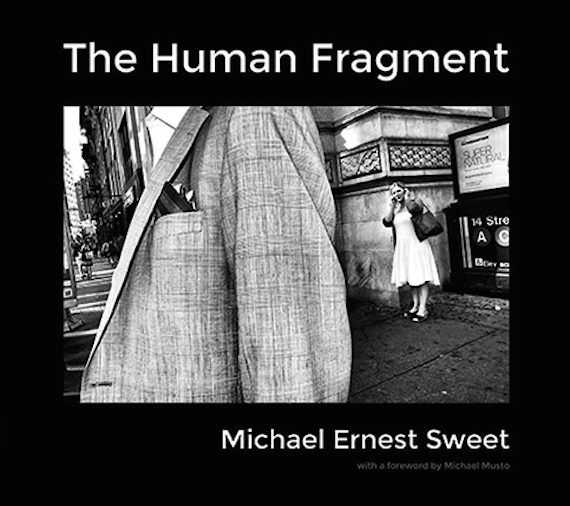

Indeed, Joe has nailed it. Most projects are premature. Successful books of photography are almost always produced by photographers who have developed a distinct and recognizable style of photography. It also has to be somewhat innovative in approach, that is you don't have to be unique, but no one is interested in publishing a Gilden copycat either. Be different. Take time to find out what that means in terms of your work. It took me many years of all kinds of approaches and techniques to develop my style. I only knew I was finally onto something when I began to see photographers copying me. Imitation being the highest form of flattery, right? It was still annoying, but it told me to press ahead as something was happening. I also received a lot of criticism, both positive and negative. That too indicates some degree of success. No one is interested in criticizing work that is pointless and irrelevant because it is unnoticed to begin with. No, people criticize work because it is coming up on the radar. As Andy Warhol used to say, "I measure criticism by the inch".

Artist Chuck Close offers some good insight here too. He comments in the documentary, Smash His Camera that "photography is the easiest medium in which to become competent. Anybody can take a competent picture, but it's the hardest medium in which to express some kind of personal vision. The fact that you can have something that is recognizable from 50 feet across the gallery, like an Arbus or a Penn, it means they really have done something." Does your work have that recognizable quality that is your own? If not, maybe continue to work on your craft and style. If you do have this, perhaps it is time to look toward publication and getting that work into a permanent home.

So, you do in fact land a book deal. Great. Beware of the publishing process. You will not be in control, the publisher will. You may, especially if you work with a small press, have some input into cover image and title etc., but often times you will not. You must be ready to sacrifice your work to a compromise. You also need to be prepared to do a lot of leg work. Unless you are with Steidl, you will be the one doing most of the promotion and selling. This may even be formally stated in your contract. However, if it isn't don't think for a second that any press is going to be amused with your hands off artiste approach. If you don't think you can sell your book, don't publish it. Simple. Furthermore, realize that no books, especially today with democratic access to publishing, sell themselves. It just doesn't happen. Publishing a book and calling it a day is like digging a hole and burying your photography. Think about all this stuff carefully. Perhaps you don't even want a book!

Finally, one of the biggest things you can do to help get your book of photography published is to BUY PHOTOGRAPHY BOOKS. I'm not talking about the classics either. Those books have already paid for themselves and the photographers, for the most part, are dead. I mean buy books by emerging artists, by your peers. If you're not interested in buying a book of photography what makes you think anyone is going to run out to the Strand and buy yours? Photography should be about community and supporting one another in a way which, collectively, benefits everyone. If everybody is merely self-absorbed, jealous, and too cheap to buy a book, then nothing is going to happen for anyone. Game over.