This past Thursday, on the 10th of November 2011, former U.N. Secretary-General, Kofi Annan delivered a speech at Stanford University on the occasion of the launch of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies' Center on Food Security and the Environment. Citing UN estimates, more precisely the UNFPA State of the World Population 2011 report, he highlighted that the world population had recently reached seven billion and growing. Advancements in healthcare and technology have increased our life expectancy, affording 'man' the ability to escape a life that is, in Hobbesian parlance, "poor, nasty, brutish, and short." Yet this apparent human success story eclipses the "shameful failure" of the international community to address an indiscernible fact: that in the contemporary technological age, an astonishing number of people in the world go hungry each day. The marriage of a globalized economy and scientific innovation was supposed to - at least in theory - increase and spread wealth and resources to enhance the human condition. And yet today - talks of unfettered markets and the financial crisis aside -, we lay witness to close to one billion people around the world who lack food security (both chronic and transitory). Citing numbers from the World Bank, Annan stated that rapidly rising food prices since 2010 have "pushed an additional 70 million people into extreme poverty". Adding to these disturbing figures is the fact that one of the world's most ravenous culprits of infanticide is no other than hunger, which claims the young lives of 17,000 children every day.

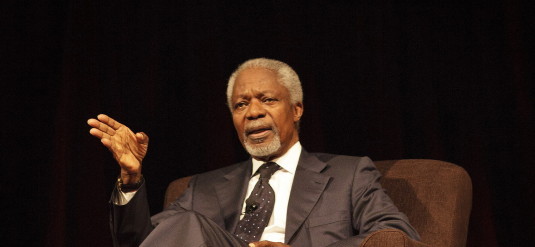

Mr. Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary General in Q & A after delivering his speech at Stanford University on 10 Nov. 2011. (Photo Credit: Ben Chrisman, courtesy of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies).

Mr. Kofi Annan, former UN Secretary General in Q & A after delivering his speech at Stanford University on 10 Nov. 2011. (Photo Credit: Ben Chrisman, courtesy of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies).

Dwindling incentives to farm and increasing pressures on farmers are not helping the food insecurity crisis. Frequently, companies who contract local farmers to produce cash crops for export do not employ "strategic agricultural planning" or take into account the impact their policies and modus operandi may have on local farming communities and their immediate (food) needs. Artificially low prices for agricultural goods force farmers from their land and discourage investment in the sector, Annan warns. Agricultural subsidies in the US and Europe against farm produce injected into the market by farmers from developing countries have also added to the problem. Agricultural subsidies in Europe in particular have had a devastating impact on farmers from other parts of the world - mostly in Asia and Africa - who simply cannot compete with the existing market conditions and the low price tags attached to their goods. This phenomenon is most acute in Africa where a significant segment of the population lives modestly by working the land and these subsidies are choking the lifeline that feeds their families. To bring home the point of the sheer imbalance between the conditions of Western farmers and the 'rest', Annan stated that with a fraction of the funds generated by a reduction of subsidies, one "can fly every European cow around the world first class and still have money left over". Without a more balanced approach to international trade policy making, subsidies will continue to be a factor in food insecurity.

And it gets worse. The 'Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse' of our times - (i) an ever emerging global water crisis, (ii) land misuse and degradation, (iii) climate change, and (iv) kleptocratic governance - have combined to aggravate an already dire international food insecurity predicament. The hard truth is that without countering the forward gallop of these ills, food insecurity cannot be adequately addressed.

The facts on the ground and projections into the future do not paint a promising picture. Food prices are expected to rise by 50 percent by the year 2050, Annan warns, and this at a time when the world will be home to two billion more inhabitants. In 40 years from now, there simply isn't enough food to nourish and satisfy the world's population.

The growing world food crisis also stifles development. It is the cyclical brutality of poverty that keeps the hungry down. Without the means or access to proper and adequate nutrition, the impoverished who are always the first victims of food insecurity invariably suffer from poor health, in turn resulting in low productivity. This vicious cycle traps the less privileged to a seemingly inescapable downward spiral.

During the course of his poignant remarks, Annan stated that without addressing food insecurity "the result will be mass migration, growing food shortages, loss of social cohesion and even political instability". He is correct on all counts. The fact is that a world which 'cultivates' and then neglects the hungry is a dangerous and volatile world. Since time immemorial, dramatic human migrations have had a direct correlation with changes in climate, habitat and resource scarcity. Survival instincts are engrained in our genetic make-up. When the most basic and fundamental necessities of life are sparse and hard to come by, our natural inclination is to look for 'greener pastures'. An unaddressed and lingering food insecurity crisis will mean the world will witness significant and rapid migration trends in the 21st century (a phenomenon very much in motion today). The injection of mass flows of people into other foreign populations will cause friction and conflict induced by integration challenges, both social and economic (surmountable, but conflicts no less).

Moreover, the desperation and unmet basic needs of the underprivileged can translate into open outbursts of conflict and violence. Tranquility and social harmony are virtues enjoyed by countries that can provide for their people. Leaving the growing food insecurity dilemma unaddressed will be to invite inevitable political instability and violence in countries and fragile regions of the world grappling with high poverty rates and concomitant food insecurity challenges. More often than not, history has shown a positive nexus between hunger and social upheaval (it bears noting that La Grande Révolution of 1789-99 was preceded by slogans of "Du pain, du pain!"). Further, it does not take too much of a forethought to recognize that it is precisely in environments of destitute and despondency where autocratic rule can easily take root and grow to inflict further suffering.

Food insecurity can also lead to wars, but similarly wars contribute to food insecurity by destroying both the land and the ability to cultivate the land. Conflict represents formidable barriers to the access and availability of otherwise usable land (countries like Somalia, Sudan, Burundi, Ethiopia and Liberia come to mind).

To be sure, "[w]ithout food, people have only three options: they riot, they emigrate or they die" (borrowed from the often cited words of Josette Sheeran, the Executive Director of the UN World Food Program).

How are we to tackle this grave problem in a realistic and effective manner? Annan rightly tells us that the "[l]ack of a collective vision is irresponsible". Implicit in Annan's remarks is also a lack of leadership to effectively tackle and untie the Gordian Knot of food insecurity. The nature and colossal character of food insecurity demands action and cooperation on a global scale. Climate change and its negative impact on the environment - e.g. diminishing arable lands, water resources, recurring drought -, one of the accelerators of food insecurity, requires robust and committed international agreement and action to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases. Strict adherence and compliance with the Kyoto Protocol and the Copenhagen Accord are a must in this regard. With strategic agricultural planning, knowledge transfer and investment, uncultivated arable lands - abundant in many parts of the world, including in Africa - can become productive and bear fruit, reducing in turn the hunger crisis. Efforts to implement more balanced international trade policies which make farming viable across continents as well as efforts to eradicate corruption (by promoting good governance) are also part and parcel of the fight against hunger. So are innovative ways of thinking about establishing, say rapid response mechanisms to preempt and effectively counter famine and other food emergencies by bolstering the capacities of relevant existing international and regional organizations. We could also reduce the threat of hunger by doing more than just pay lip-serve to the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and uphold our commitments to the MDGs through sustained funding and support.

The UN and other multilateral bodies and pacts are tools we have created to work collaboratively - as best as human frailties permit - to confront global challenges and ills that threaten the social fabric of human society (whether they be food insecurity, dearth in development, war and the crimes that emanate from aggression which threaten peace and security, inter alia). Our capacity to reason, innovate, communicate and cooperate is hence an indispensible tool in our struggle to keep the peace, to protect our fundamental human rights and to satisfy our most basic needs for survival. It's time to put these faculties to work in confronting the world's food security challenges. It is only fitting to conclude these brief remarks by quoting from the man and the lecture that inspired them. "If we pool our efforts and resources we can finally break the back of this problem", stated Annan in his call for action to defeat food insecurity. If there's a will, history tells us, change is within grasp, no matter how daunting the task. It only takes the trinity of courage, commitment and leadership.