God is not dead. Fundamentalists are seemingly creeping up everywhere. And despite their spectacular growth, Mormons were never more in the public eye than when they were being targeted in the 19th century.

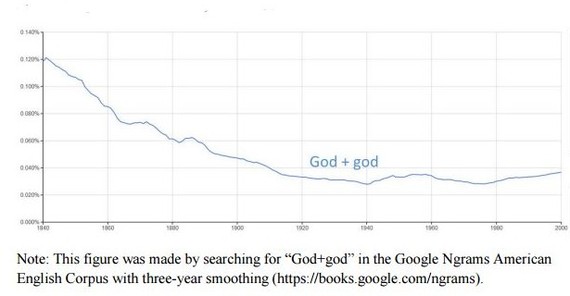

These are some of the interesting revelations that are suggested by searching an American literary canon of more than 3 million books from 1800 to 2000.

In partnership with more than 40 university libraries, Google digitized more than 15 million books, and developed an Ngram Viewer, which allows users to determine the frequency of words and phrases in several million books beginning in 1800.

When it was introduced, the Ngram Viewer was hailed as an advance in "culturomics," enabling individuals to instantly search a massive collection of published works - encompassing 361 billion words in English alone - for insights into human culture over time.

The viewer can be a particular godsend to those seeking information on trends in religion, note sociologists Roger Finke of Pennsylvania State University and Jennifer McClure of Samford University. Data on religion since 1800 is relatively lacking compared to statistics on subjects such as immigration, education, employment and crime collected by the census and other government agencies, they state.

Their research on religion and the Ngram Viewer is part of an upcoming book on "Faithful Measures" that analyzes methods of gathering and understanding religion data.

The Ngram Viewer still requires a human touch. Lower literacy rates and a much smaller percentage of secondary school graduates in the 19th century meant books were written for less diverse audiences. And without an in-depth background in American religion, much of the raw data can be easily misunderstood.

Overall, however, "Ngram is just a wonderful tool for helping us look more objectively at cultural trends," McClure says.

Anyone can search terms using the Ngram Viewer. But the Association of Religion Data Archives at Penn State, in a project led by Finke, McClure and Nathaniel Porter, has made it easier by creating a dataset exploring several hundred variables from angels to Armageddon.

In their study, Finke and McClure report that the Ngram Viewer can offer important data in areas relating to historical trends, changes in meaning of terms over time and what rises to the top in terms of public interest in religion. (Of little surprise to consumers of contemporary media: Bad news travels faster.)

Do God and atheists need a publicist? In 1840, about 12 out of every 10,000 words referred to God. By 2000, only 4 in every 10,000 words referenced God, prompting some to ask whether God needs a new publicist.

Others might be tempted to claim this represents a dramatic growth of secularization in U.S. society. But Finke and McClure also note a steep drop-off since 1810 in the frequency of the use of the word atheist.

What they think could explain the changes are more diverse audiences and publishers. Many of the earliest colleges were started to train clergy. From 1810 to 1860, more than eight in 10 college students attended institutions sponsored by a religious denomination. As late as 1870, 20 percent of the population was illiterate and only 2 percent were high school graduates, the researchers note.

As near-universal literacy became the norm, references to God began to plateau. In the 1990s, there was even slight growth. And four in every 10,000 words for God is no small change today. Considering that by one estimate the median book is about 64,000 words, that would mean about 25 mentions of God per publication.

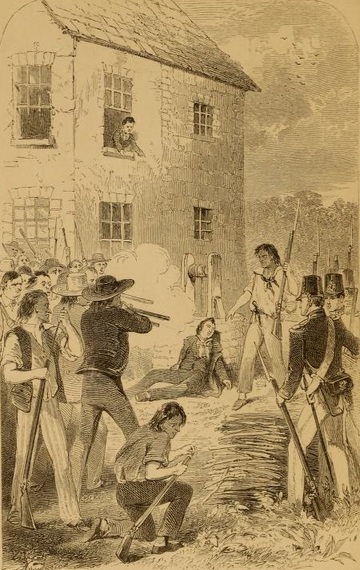

Violence and sex are always best-sellers: Mitt Romney, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ran for president in 2012, and the church has grown to more than 6 million members in the U.S. But words like Mormon or Mormonism first became popular in the 1840s when the fledgling movement was enduring violent persecution, with a mob killing Joseph Smith, the movement's founder, in 1844.

The high-water mark for literary references to Mormons came around 1890 at the height of the controversy over multiple marriages, Finke and McClure report. Polygamy was declared a felony in 1887, and three years later the church agreed to obey laws prohibiting more than one spouse at a time.

Not sticking to the fundamentals: Fundamentalism arose in the late 19th century as a Protestant movement defending conservative Christian beliefs. A collection of 90 essays called "The Fundamentals" was published from 1910 to 1915, and a Baptist editor coined the word Fundamentalist in 1920.

Still, by 1930, just five out of every 10 million words in books used the adjective fundamentalist, Finke and McClure point out. That percentage jumped fourfold by 1990, when the term used to define Protestants who believed in the literal truth of the Bible was suddenly being used to describe Catholics and members of other religions such as Islam.

All of these findings illustrate both the great potential of the Ngram viewer for revealing religious trends, and the need to analyze the data in context, such as being aware of the limited pool of authors in the early 19th century in the case of references to God and atheism, Finke and McClure note.

Similarly, the spikes in interest in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are best understood in relation to historical events such as their early persecution and later struggles with polygamy. And comprehending the growing use of the term fundamentalists requires background of its radical change in meaning over time.

On a personal note, as the lead religion writer for The Associated Press through much of the 1990s, I would get calls from bureaus around the world asking me what the term meant as it became increasingly used -- often in a deprecating manner - to describe a wide range of individuals or groups of people that did not claim the term for themselves.

I would try to explain the original meaning of the term, and how its use was changing.

In the end, however, my shorthand answer was: "A fundamentalist is anyone you disagree with."

Image from ARDA/ASREC Working Paper by Roger Finke and Jennifer McClure made using Google Ngrams Viewer.

Image Public Domain, 1851 (cover inset in The Mormons or Latter Day Saints: A Contemporary History.

David Briggs writes the Ahead of the Trend column for the Association of Religion Data Archives.