Can New York City survive the sea?

This is the question Ted Steinberg, a Case Western Reserve University professor, poses in his recent book, Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York.

From the days when Mannahatta island was home to the indigenous Lenape tribe to today's five-borough metropolis that houses more than 8 million people, one thing has remained constant: the story of New York City cannot be separated from water.

The city received a painful reminder of this two years ago when Hurricane Sandy struck the region, killing dozens, causing billions in damage and paralyzing the city's transportation system. Sandy's record-setting 13-foot storm surge revealed the vulnerability of Lower Manhattan in an era of rising sea levels.

The Huffington Post spoke with Steinberg about the city's aquatic history and what the future may hold for Gotham.

What first prompted you to study New York City’s ecological history and its relationship with the sea?

First, simple intellectual curiosity about the metropolitan area where I was born and raised. And, second, I wanted to see how one of the most massively altered spots on the planet held up ecologically when 6 percent of the U.S. population was crammed in there.

How is greater New York’s history defined by water?

Water is the key to New York’s history. There is no way that the island of Manhattan could have ever supported such a dense population on the natural springs and ponds that once dotted the landscape. It took the importation of incredible amounts of water from distant sources -- the Croton River, the Catskill Mountains and the Delaware -- to underwrite New York’s explosive population growth beginning in the nineteenth century. Moreover, this huge increase in the amount of water coursing into the city eventually -- through the development of an intricate sewer system -- ended up in New York Harbor where the nutrients in the sewage robbed the water of oxygen and compromised the biodiversity of marine life. In short, it’s impossible to fully understand New York’s history without considering the role water has played.

It's easy for many visitors to New York City, and even residents, to miss the fact that it’s a coastal city and inextricably linked to the sea. How can people rediscover New York’s maritime past and experience this coastal connection?

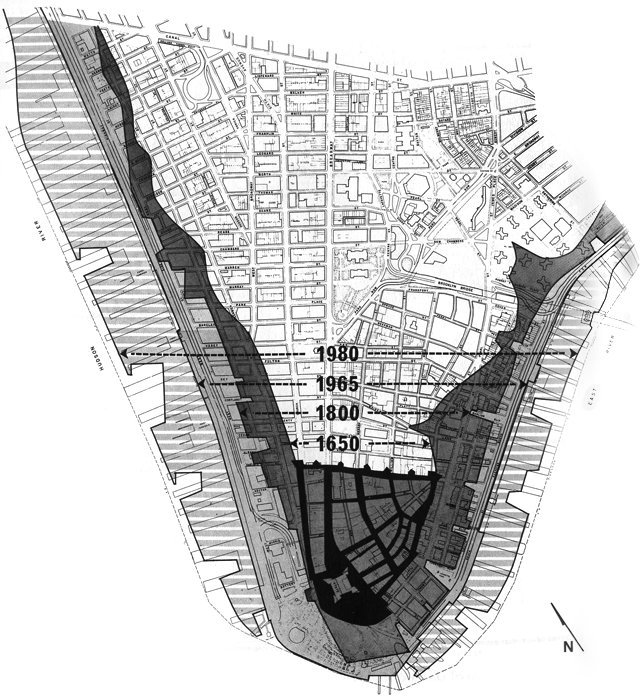

There are of course many tourist attractions that allow people to gain access to the waters of New York Harbor. But my feeling is that the most revealing way of experiencing the city’s link to the sea is to wander Lower Manhattan with a good map in hand that will show you how much of the island has been reclaimed at the expense of the surrounding waters. Much of the World Trade Center [site], for example, is built on what was once open water. Anyone who understands the island’s historical geography would not be the least bit surprised to learn that the 9/11 Museum was flooded during Hurricane Sandy.

The New York City area has lost a tremendous amount of wetlands since the 19th century. Is this trend continuing? How does past wetland loss still affect the city today?

The massive decline in greater New York’s wetlands began to abate in the 1980s and today there are even some small-scale efforts afoot at various sites -- Swindler Cove in Manhattan and Soundview Park in the Bronx -- to restore the marshes. To put these recent efforts in historical perspective, I should point out that as late as 1904 some 300 square miles of marshland thrived within a 25-mile radius of city hall in Manhattan. That is an area about one-quarter the size of Rhode Island, and it’s effectively gone forever. There are no wetland restoration efforts now or planned for the future -- nor could there be really -- on a scale that could possibly recover the metropolis’s long ago past of marsh and muck. And today, instead of the old wetlands that once buffered the city and filtered impurities from the water, New York has in place a massive wastewater treatment system at risk of being overwhelmed by storm surge.

In a recent talk at New York University, you discussed the sobering fact that 400,000 New Yorkers live within the 100-year floodplain. This is more than in any other U.S. city, including New Orleans. Do you think many people are aware of this?

I would tend to doubt it. This is not something that the city of New York goes out of its way to advertise. Nor are New York’s boosters likely to let you know that nearly half the land area of the five boroughs exists in a hurricane evacuation zone. I doubt that’s something people think about when they wake up in the morning.

You’ve articulated the idea that there’s a “growth imperative” in New York City. How has this shaped the city’s history and what does it mean for the prospect of adapting to rising seas and a changing climate?

The idea of New York as a limitless proposition -- that the city can grow and grow in terms of population, land values, and, until recently, with respect to its relations with the sea -- is one of the most important developments in the city’s environmental history. This idea can be traced all the way back to the third quarter of the nineteenth century, to a time when New York real estate was thriving, in part because of a sixty-seven year lull in major storm activity in New York Harbor. There were no significant hurricanes or nor’easters to speak of between 1821 and 1888. This idea of limitless growth has helped to degrade the surrounding waters and to promote an enormous amount of building on low-lying ground at the expense of the region’s once magnificent wetlands. It’s not likely that New York will be able to grow itself out of the problem posed by rising seas. Some kind of strategy for retreat must at least be one of the options on the table. A moratorium on all development in the city’s first-line hurricane evacuation zone makes some sense to me. Why continue to tempt fate?

It seems likely that the New York region may look dramatically different in a few centuries, due to impacts from climate change, a retreat from low-lying coastal areas, major infrastructure to ward off the sea, or some combination of the three. What do you think New York’s history can tell us about its future?

I think historical thinking needs to play a role in how those in power think about the future of New York. Thus far virtually all the discussions and plans for the future of New York have taken place without any consideration of the ways in which the past structures what is possible here in the present and beyond. The most likely scenario is that sea level around New York will rise anywhere from eleven to twenty-four inches by the 2050s, aggravating the problem of coastal flooding. Obviously, it’s not as if we can pick up New York City and move it inland to somewhere in Westchester. That is simply another way of saying that past historical developments -- stretching back to the creation of a market in land under water in the late 1600s -- have shaped what can now take place going forward in a city that has thrived by building on low-lying ground. To paraphrase James Baldwin, history is something we all carry within us, that’s there in everything we do. All I can tell you is that whatever the future holds, it will be shaped by the countless decisions and choices made with respect to land and water that have unfolded over the centuries.

This week is the second anniversary of Hurricane Sandy. What do you think we learned from it? How do you think it will be remembered in the history of the region?

I think the storm served as a wake-up call to those who rule New York. After all, the Bloomberg administration lost no time in producing a massive 400-page report just a few months after the disaster. Clearly the risk of coastal flooding is more at the center of the collective consciousness and some important reforms have taken place—sensible steps such as a more precise hurricane evacuation plan, installing backup generators at housing projects, raising the electrical systems at hospitals. All this is very positive. Nevertheless, I would say that Hurricane Sandy has done little to slow the yen for growth in population and development. One projection is that the city will add another 800,000 people by 2040 -- a population about the size of Amsterdam’s -- as new housing goes up in vacant industrial zones along the East River. Hudson Yards, meanwhile, is being built on the West Side and much of the project is in the 100-year floodplain. The fact is that the Bloomberg administration made the idea of retreat into a dirty word. I don’t exactly see Mayor de Blasio embracing the idea either. But if the question is how should Hurricane Sandy be remembered. My answer is this: As an object lesson in the limits to growth.

The Hugh L. Carey Tunnel, formerly known as the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, was flooded during Superstorm Sandy. (AP Photo/Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Patrick Cashin)