By Steven Kelly. Contributor at the International Political Economy Hub blog.

It was September 17, 2008, two days after the infamous bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers investment bank, when the Reserve Primary Fund "broke the buck." The Fund--a so-called "money market mutual fund" (MMMF) that typically earns higher returns than a savings account yet still promises its investors that its shares will never fall below 100 cents on the dollar--had broken its promise. The $65 billion MMMF, having indirectly fallen victim to the mortgage delusion of the early 2000s, announced that its investors would only be able to receive 97 cents per dollar of their investment holdings, prompting the Treasury and Federal Reserve to respond with various assistance measures meant to prevent a Depression-style bank run from taking hold across the MMMF market and deepening the financial panic.

In the wake of the financial crisis, governments across advanced economies are attempting to better regulate these funds to prevent them from contributing to any broader market turmoil or needing government assistance in the future. During the crisis, MMMFs found out the hard way that some of the private assets they had invested in--such as the mortgage-backed commercial paper of some financial institutions--weren't as safe as government Treasuries, as was previously thought.

The U.S. is now rolling out new regulations that will allow MMMFs to delay share redemptions by their investors if the funds are invested in private sector assets--to help prevent runs and asset fire sales during periods of negative investor sentiment. Similarly, lawmakers in Europe are developing a law that would mandate that funds allow their share values to float (i.e. not always maintain a value of one euro) if they are invested in private assets. Thus, MMMFs across these markets are faced with a difficult choice. They can either continue to invest in private assets at the risk of losing business from investors being worried that they won't be able to access their money at all times or in its totality, or they can convert to investing solely in government assets, as many are already.

As these regulations are put in place, they have will have two major adverse consequences. The first is that, for the funds that choose to stay invested in private assets, the MMMF shares will face a reduced level of "moneyness." That is, the delay in availability in the U.S. and the uncertainty in value in Europe mean these assets will be less spend-able for investors and less valuable as collateral in other financial transactions. This will reduce the supply of money equivalents/safe assets--a supply that has already been harmed since 2008--and push down the safe asset equilibrium interest rate. The higher borrowing costs and reduced asset creation on the part of companies that usually borrow from MMMFs will have the same effect.

Secondly, to the extent that funds are shifting out of private assets and into only safe government assets, the demand for safe assets--greatly elevated since 2008--will increase further and push the market-clearing interest rate on safe assets even lower. Both aforementioned effects, by reducing the safe asset equilibrium rate, will reduce the stimulative effects of central banks that are trapped at their policy rates' lower bounds.

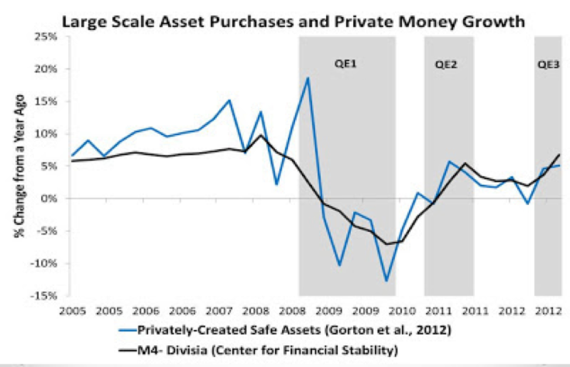

Given the drag on the U.S. and European economies that these outcomes will create, policymakers could respond positively in two ways. On the monetary policy side, central bankers could expand their easing measures to allow for more private safe asset creation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - While the first round of quantitative easing (QE) was designed to limit the fall in money and safe asset supply, the U.S. Federal Reserve's willingness to execute QE2 and QE3 helped boost creation of private safe assets and money equivalents. Picture courtesy of David Beckworth's Macro and Other Market Musings.

These private safe assets would retain many of the qualities of money and would help offset the decline in safe assets due to the new regulations as well as reduce the likelihood that MMMFs invested in private assets would see their share prices deteriorate, thus making them safer. The second option is for safe-asset-issuing governments (the U.S., Germany, Netherlands, etc.) to simply issue more debt, easing the downward pressure on central banks' policy rates due to the new regulations and thus avoiding making the policy rates less effective at spurring economic activity.

However, the politics in the U.S. and Europe that surround additional central bank intervention and arbitrary fiscal rules leave these potential solutions just a notch above fantasy.

While regulations created in the aftermath of the financial crisis have been enacted eagerly, the enacting governments are failing to perform their newfound responsibilities.