Even now, in the midst of the 'Great Recession', there are at River House, many quietly detailed duplexes and an intact triplex maisonette, commanding superlative views and phenomenal prices. Some apartments, however, are not quite as grand as others and none as improbable as the long subdivided suite at the building's summit.

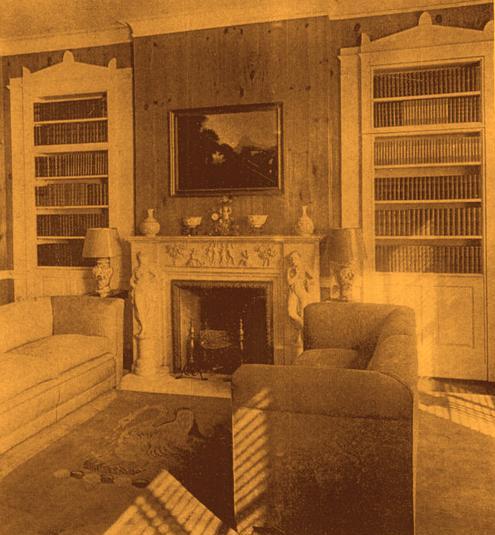

Privileged William Rhinelander Stewart, Jr's 'ground-floor' flat at River House boasted the piano on which Gershwin composed the "Rhapsody in Blue," an Italian marble mantelpiece, from his ancestral home on Washington Square, a carpet woven with his family crest, and a secret door in a library bookcase.

Marshall Field's English Georgian library at River House was adorned by superb Impressionist paintings such as Claude Monet's Boulevard des Capucines

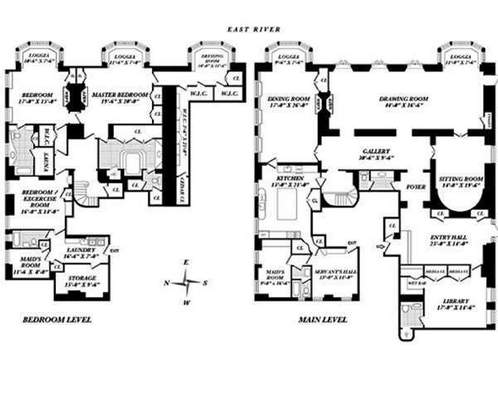

Surmounted by a ballroom in the tower's graceful cupola, this most palatial apartment at River House was a triplex occupied by the family of sportsman and publisher, Marshall Field, III. On Sept. 28, 1943, at 50, he inherited the bulk of the $140,000,000 fortune his grandfather had established in his famous department store and grounded in Chicago real estate.

However, even as an Eton schoolboy, Marshall Field was already 40 times a millionaire. In 1917, following Cambridge, he'd helped to initiate a reputation as a progressive by returning to the States to enlist as a private in the army. Returning from France a cavalry captain, despite his connections, Field next became a lowly brokerage salesman; destined to pile success upon success.

He was wed to New York debutante Evelyn Marshall in 1915. Her brother, Charles H. Marshall, would marry Brooke Russell Kuser and become stepfather to the eventual Mrs. Astor's notorious son, Anthony Dryden Kuser, who took his name. By 1925 the Marshall Fields had left Chicago for New York's greater business opportunities and social prospects. Naturally, given Field's English background, English style houses were felt to be in order. Buying a 2,000-acre estate at Lloyd's Neck on Long Island, he built a magnificent Georgian mansion overlooking Long Island Sound. At Caumsett, a Georgian stable, numerous cottages and barns, a boathouse, a power plant, and a 20-car garage complimented the 'big house'.

In Manhattan, Chicago's most revered residential architect, David Adler, designed for the couple another lavish neo-Georgian residence, at 4 East 70th Street. One of the largest and most elaborate private houses ever built in the city, it stood for a mere 10 years.

When his first wife divorced him in 1930, Marshall Field gave her an uncontested $1,000,000-a-year income and custody of their three children. Two weeks later he acquired an English-born wife to preside over his English style abodes. God-daughter of King Edward VII, Audrey James Coats was a socialite and widow of a British Army captain.

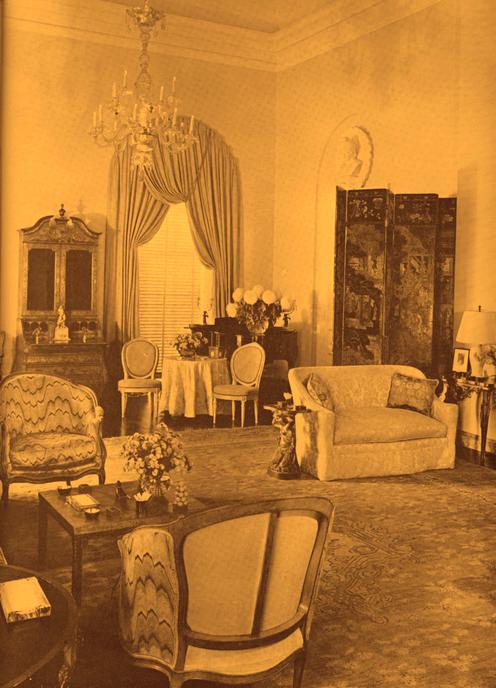

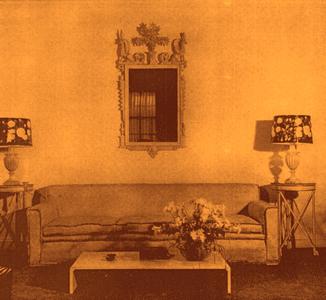

Mrs. Diego de Suarez, the first wife of Marshall Field, is advised by her decorator, and River House neighbor Eleanor McMillen Brown. Mrs. de Suarez's double-height drawing room was designed by her husband in collaboration with Mrs. Brown

If in the aftermath of their divorce Field's second wife returned to England and 'civilization,' the publisher, his children, his first wife, and her new husband, Diego de Suarez an architect, were happy enough to live conveniently apart, but close by, at River House. And, offering solid proof of the building's unmatched social connections, when Field and his best friend's former wife Ruth Pruyn Phipps were married in 1936, the ceremony and reception took place in her parents' River House apartment.

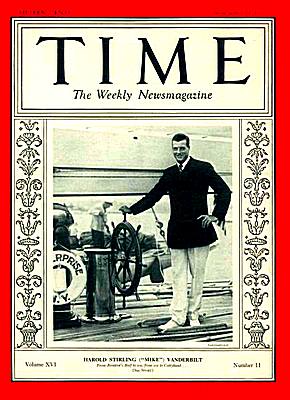

Harold Sterling Vanderbilt, who twice defended (won) the America's Cup, also invented contract bridge

Long after leaving Yale, Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney remained a keen rower

The splendid Harold S. Vanderbilts, the Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitneys, the James A. Burden, Jr.s, the Harry Cushings, the William Rheinlander Stewart, Jr.s,

New York City congresswoman Ruth Baker Pratt, and three of the city's leading architects, including William Lawrence Bottomley, who designed River House, Maurice Fatio and ...

the subject of an exceptional monograph by Susan Hume Fraszer, William Lawrence Bottomley, was born and reared in Harlem. He designed River House in close association with his partner Sidney Wagner. Seen above is an engraved moonstone and diamond pendant Bottomley designed for his wife and the staircase, (forged by Hunt Dietrich), and drawing room of their River House triplex, which the Depression would force them to divide

Archibald Manning Brown, whose wife Eleanor was the founder of the distinguished decorating firm, McMillen Inc., all helped to give the building a very patrician character indeed.

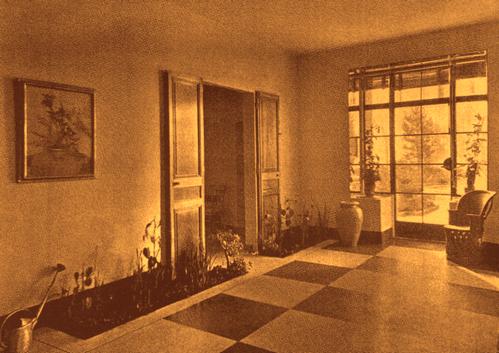

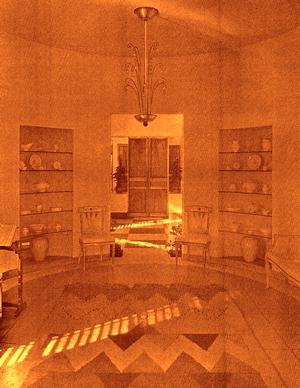

Archibald Manning Brown with his wife Eleanor McMillen Brown, the well known interior designer, occupied a sun-filled, duplex maisonette that was a tribute to Scandinavian proto-modernism and opened directly onto the River House garden. It was owned much later by pharmaceutical heiress Mary Lea Johnson Richards and since her death has been offered, unsuccessfully, for 10 years, for sale by her husband, acclaimed produce, Marty Richards

This glittering tenancy helped to attract rich, self-made owners and mid-Westerners alike.

Clare Booth and Henry Luce, Walter Hoving and his richly-widowed, older wife and Frederick W. Patterson of

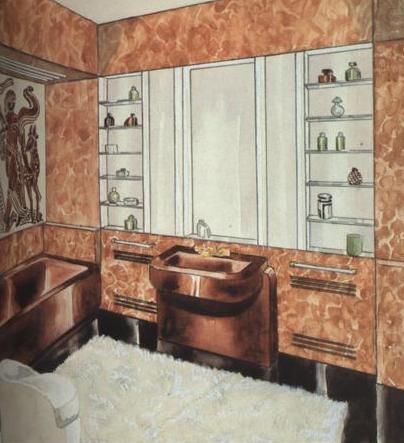

Leaving an old-word manor house in Ohio after a bitter divorce, at River House Frederick W. Patterson and his new wife ask dynamic modernist Donald Deskey, to come up with something completely different

the National Cash Register Co. of Dayton, Ohio had each moved here by mid-decade. From 1935 until about 1945, so anxious were shareholders about a growing deficit that they had authorized apartments to be rented with an option to buy. In 1938 a 6 room suite with four baths, four maids' rooms, a kitchen, pantry and servant's hall could be purchased for just $20,000!

That's just what George Perkins and Marta E. de Cedercrantz Raymond did in 1937. A compendium of 30's elegance with a collection of drawings by friends like Porter Woodruff and Jared French and a sophisticated mix of European and American furnishings, theirs was one of the more modest available in the esteemed building.

Mrs. Raymond in a gown called ''La Sirene'' (''the Mermaid''), designed by the audacious American couturier Charles James in Paris in 1938.

A former model and fashion editor whose father was a lawyer for the king of Sweden, Mrs. Raymond made what could have been a conventional decor into a smart personal environment.

Both living in Paris since the late 1920's, the Raymonds had met at a party, in 1931. Six-foot, one-inch tall, she spoke six languages and resembled Marlene Dietrich. A widower, he had been quickly smitten. Indeed, so impressed was the foot-shorter aspiring concert singer from Akron, whose Perkins grandfather had made him a beneficiary of a $3,000,000 spendthrift trust derived from investments in the B. F. Goodrich Tire & Rubber Co., that, that very afternoon, he made a note in his diary. Concerning a party he was to host the following week, it read "invite tall Swede."

Married on August 29, 1932, five years later, they moved to New York with Mr. Raymond's two children from his previous marriage. Stylish without being ostentatious, and traditional without being oppressive, encapsulating every aspect of a gracious and social way of life, River House was the Raymond's first choice for a base in the city, Marta Raymond told me at our first meeting.

Reminiscent in its eclecticism to the Raymond apartment, the River House home of one-time dancer Mrs. Bradford Norman featured a music room with two pianos for impromptu concerts. This room also displayed the most arrestingly beautiful mirrored screen ever made, which was the work of French designer and portrait painter Etienne Drian

Offered Clamato juice and salted almonds, I delighted over mahogany Empire furniture from the Stone House, silvered, shell-form grotto chairs, an array of monochrome Chinese porcelains, fancifully molded glass bottles and colored cut overlay glass decanters on the lacquered sideboard, mirrored commodes and the mirrored jambs and soffits of the windows reflecting sky and water.

Reverently eoccoativ, the River House pied-à-terre Joseph Mullen designed for Mr. and Mrs. William Robertson Coe, exhibited exactly the kind of excessively derivative style people like Marta Raymond or Mrs. Norman were trying to get away from

If River House had bewitched me with its enchantment from my first encounter, Tom Hoving, the Metropolitan Museum of Art's most dynamic director of all time, who during a respite as Parks Commissioner helped to stop Columbia from building a private gymnasium in a public Harlem park, regards it rather differently.

In a memoir posted online at artnet, entitled Artful Tom, that's every bit as compelling as Hoving's earlier bestseller Making the Mummies Dance, he relates how the opulent apartment occupied by his father, who variously headed Lord & Taylor, Bonwit Teller and Tiffany & Co., came to embody all of the remoteness and false values he saw in his father and his second of three wives.

"My first meeting with my stepmother," Hoving recalls of River House, "is seared into my memory. The building had a large iron gate and a circular drive. The entrance was a revolving door and Nanny let me push it around a few times as the doorman looked on sourly.

My instant impression of the interior was yards and yards of black and white polished marble floors through long, wide corridors. The entrance opened up onto a spacious, elegant hall with a series of glass doors looking out over a small garden. In all the years I visited River House I was never allowed to enter that garden, which became for me the symbol of needless exclusivity. I wonder if this prohibition led to my egalitarian tendencies. I couldn't understand why I couldn't play there. And to this day I have been contemptuous of the trappings of wealth like gated communities that exclude anybody but the privileged."

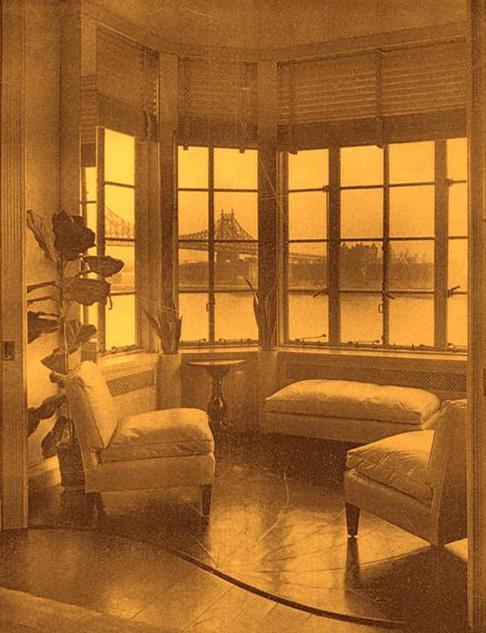

Hoving's father and stepmother, Walter and Pauline , he explains, lived on the ninth floor. "The apartment door was open and two uniformed maids were standing there. One maid took our wraps and another guided us through a nearby door, which led into an oval library where my father and stepmother Pauline were standing... The library..., had a large fireplace on one side. Straight ahead was a bay window looking out over the East River and I stood for several minutes, entranced, as tug boats cruised by and that would become my favorite place in the apartment. The East Side highway was under construction and I spent hours watching the work. I remember a huge illuminated sign across the river, "Uneeda Biscuit."

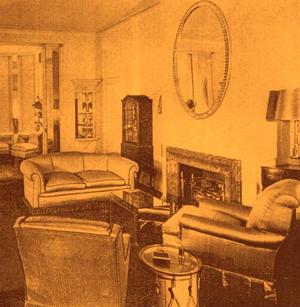

The library gave way onto a long, rectangular salon filled with overstuffed sofas and chairs upholstered in gold and silver satin. Pauline smiled stiffly and said, "Little boys and girls must never put their fingers on this upholstery."

The room contained a concert piano (I never heard it played) with another fireplace (which I never saw used). I don't recall ever being invited into that grand salon. Chic late Impressionist paintings adorned the main wall -- they were by a fashionable painter of the early Twentieth century, Suzanne Eisendieck. One was a lovely, sweet woman dressed in a frilly white costume holding some white flowers on a whitish ground - she looked like the upholstery. Over the years I'd sit on the floor beneath the painting and look at it for hours. She was nicer than Pauline.

Formidable matron Pauline Hoving in her River House drawing room consults with inovative decorator William PahlmannThe salon entered into a spacious dining room. We were then taken through the bedrooms. Pauline's was a suite of three rooms, including a walk-in closet with a large safe with trays for her jewelry, which fascinated me. My father's suite had two rooms.

In the back were more family rooms and the servants' quarters. One room had a massage table and a stationary bike. I wanted to give the bike a try, but Pauline said it wasn't for "little boys." I never did use it. At the end of the corridor was a spacious, impeccably decorated room with twin beds, a dressing room and bath. This would be where I was sequestered the rare times I ever stayed overnight."

To be continued...