A Tale From Samos

It was a starless night, a night like many nights, when the beguiling Aegean turned its once inviting crystal blue waters into soulless liquid tar, whipped by the screaming wind and boiling with fury. Imagine being one of thirty tormented souls in pursuit of hope and decency, running away from death and misery, stacked inside a rotten fishing boat. No horizon in sight, no distinction between sea and sky, no difference when you blinked. Children, women and men, faceless sardines inside a wooden can, no name, just a transaction. After a long journey, a lot of tears and pain, they bought a ticket to the elusive Land of Plenty. The smuggler promised he would take them there for $2,500 per head, but the beating from the waves scared him. Why risk his life for the sardines?

A few years ago, the Hellenic Navy gunboat 'Ormi' was patrolling around the Greek islands Chios and Samos. Towards the end of a routine patrol, while the vessel was underway to Chios for replenishment and to take shelter from the upcoming storm, an urgent cable arrived. A subhuman trafficker -- or the teenage boys often called to do his dirty work -- intimidated by the worsening sea conditions threw the breathing load overboard into the ebony waves off the coast of Samos. After hours of pounding in the rough sea, Ormi finally reached the wet cemetery. The search light revealed only white tipped waves; nothing else, not even a single life vest since such a luxury was not included in the price. The first rays of the sun revealed the diabolical work of the smuggler, lying lifeless against the rocky coastline. Most of them were swallowed by the hungry sea a few hours ago and some were spitted out as cold reminders of a stark reality that has been nothing but routine for the Greek islands of the Eastern Aegean.

The rusty gate of dreams

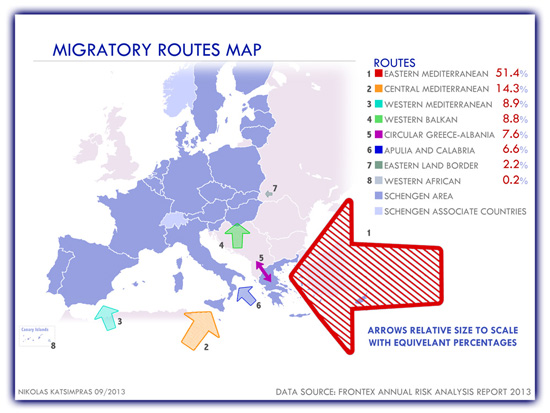

Greece has been chronically the recipient of swarms of financial migrants and refugees due to its vicinity with Asia, its relation with the European North and until recently, its elusive financial prosperity. Turkey being an arm's reach away is such a convenient location for smuggling migrants inside flimsy dinghies. For decades, the deleterious inexistence of an appropriate migratory policy has created an unfortunate situation for both the impoverished migrants who end up in Greece and the local population who bares the toll of the uncontrollable influx. According to FRONTEX, the European Union agency for external border security, there are eight main migratory routes into the EU through land and sea, ranging from the Canary Islands, to the southern borders of the EU in the Mediterranean, all the way up to the eastern borders of the Baltics. Greece is the gateway of the Eastern Mediterranean Route (EMR), which in 2012 attracted a staggering 50 percent of the incoming migrant traffic towards the EU, as reported by the latest analysis of Frontex. The Circular Greece-Albania route boosts this number to a total of almost 60 percent, constituting border control a Herculean task for the crisis struck nation.

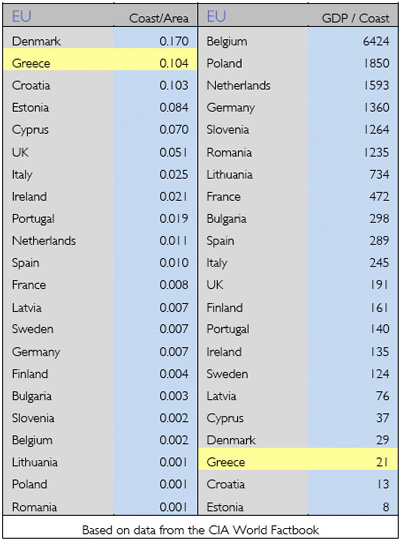

EMR has been consistently the number one migrant passage, with the traffic deriving from the east without much control from neighboring Turkey reaching a seasonal peak in the third quarter of each year. For numerous years, the border-crossings through Evros, at the northern borders of Greece, had been about a couple thousand hope-pursuers a week. However, in August of 2012 there was a dramatic drop in these numbers due to the decisive measures taken under the leadership of the Minister of Public Order and Citizen Protection, Nikolaos Dendias -- unfortunately a sole bright exception in the disintegrated political landscape of Greece. Mr. Dendias mobilized an extraordinary amount of resources by Greek standards, by deploying 1,800 border patrol agents at the land borders with Turkey, under Operation 'Aspida' (Shield). As a result, the illegal crossings dropped from a couple thousands in the first week of August 2012 to an incredible 10 per week in October. The robust measures in the land borders forced the smugglers to start shifting their preference towards the Aegean Sea route, which brings up another Greek peculiarity. The archipelago nature of the Aegean along with the winding peninsular-formed mainland sets the length of the Greek coastline to an incredible 8,500 miles. This number alone might not say much, however when compared to the 12,380 miles of the U.S. coastline and 41,000 miles of the EU coastline, one can begin to fathom the level of challenge. Greece, with almost the size of Alabama or a quarter the size of France, is responsible for guarding a coastline 70 percent the length of the U.S. coastline and 20 percent of the EU. As a matter of fact, Greece has the second highest Coast to Area ratio in mainland EU, after prosperous Denmark, and the third to last GDP to Coastline ratio. In other words, tiny Greece has been called to guard an immense coastline from the biggest surge of migrants in the EU, while struggling with one of the worst financial crises in its eons-long history.

This discussion -- along with numerous others regarding Greece's current situation -- would have been completely different, had Greece not been a part of the EU. Greece's EU membership is one of the reasons why Greece is so appealing to migrants. They no longer consider it a destination but the gate to the rich North. Unfortunately, the hybrid union on the other side of the Atlantic shows once again one of its tragic flaws. Instead of the member states dealing with immigration on a collective basis, as one would expect given the use of the word 'union' in the name of the supranational entity, they have opted for an obsolete approach which transitions the weight of the responsibility to the peripheral countries. Greece is expected to be successful with the extremely complex task of migrant traffic management, with disproportionate contribution by the EU. This means that a nation of ten million people has to devote appropriate resources to manage most of the incoming migrant traffic towards the EU of 500 million people.

Managing traffic means guarding the vast borders, providing temporary shelter, facilitating and processing the eligible asylum seekers and successfully repatriating the ineligible individuals. According to a recent statement by Mr. Dendias, the annual cost of the comprehensive migrant management plan is a staggering 500 million euros, with Greece contributing a disproportionate 247 million and EU 178 million euros. While Greece is grateful, Mr. Dendias says, for the EU contribution, the financial toll is still exorbitant for the shrunken Greek budget with a pending remainder of 75 million euros. The asylum-seeking process is even more so complicated due to the Dublin II regulation, which determines that the country of first entry is responsible for the time and highly skilled resources-consuming task of processing the asylum claims, regardless of the final destination. Even if an asylum seeker gets to her intended host country, she is being returned back to the state of initial entry for processing. Even though Sweden and Germany receive two-thirds of the asylum applications, the applicants are still returned to the peripheral entry states, with Greece maintaining the lion's share. With the 60 percent of entries taking place in Greece, one can begin to grasp the additional challenge for the Greek authorities which need to balance the basic humanitarian principles with the duty of safeguarding the borders and the rule of law. In addition, Greece has also been facing the complete unresponsiveness of the primary countries of origin like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Algeria and Morocco, which makes the task of repatriation almost impossible.

Conclusion

During the past year, Greece has shown substantial results in handling the great volumes of migrants despite its financial problems. However, these results are not sustainable and have unfortunately come at the expense of the asylum process. The abysmal asylum processing rates of Greece are heavily dependent on the baffling stance of the EU, despite the best intentions of the government, which in the end had to make the best quick impact decisions for its country. EU has to now rise up to its responsibilities. The initial force of 1,800 patrol agents that was able to control the influx for a year has dropped to a mere 550 with Operation Aspida winding up by the end of September. The only way that Greece can sustainably handle such an immense challenge with respect to human rights and decency is with robust financial and logistical support from its partners and allies. The latest risk assessment of Frontex warns about the risks of resurgence of irregular migration due to numbers of migrants waiting in Turkey for the wave of measures to dissipate. Given the increasing numbers of Syrian refugees reaching the coast of Asia Minor, it is even more so imperative for the EU to reassess Dublin II and assist Greece with managing the great influx in order to finally process the asylum applications of the people escaping from the nightmare of war in a humane manner and timeframe. The Europeans need to establish specific qualitative and quantifiable relocation quotas between the member states based on the GDP and the population of each member, in order for the responsibility to be distributed in a fair and effective way. Greece has demonstrated its best intentions in dealing with the problem by both mobilizing a great amount of resources and beginning to restructure its police force around the issue of immigration control. It is now Brussels' turn.

Migration is not a single country's problem. It is a profound indication of our growing global interdependence and our collective responsibility. The impending trends of westbound waves of financial, survival and, in the near future, environmental migrants demand us to start putting a face into the faceless ignorance of the current policies. As far as the Greek side of the issue is concerned, the U.S. can help apply leverage to both persuade the EU towards reassessing its policies and encourage Turkey to improve its cooperation, while discussing the repatriation challenges with the uncooperative countries of origin. Apart from the apparent security concerns of the U.S., given the alarming numbers of fraudulently documented travelers in the EU, the issue of migration also resonates here at home on a very basic level that reaches into the very iota of the American identity. The "inalienable rights" of Life, Liberty and pursuit of Happiness extend beyond the national identity and transcend into our very core sense of humanity. It is time for policies to start demonstrating empathy across both space and time. It is time we stopped treating people like sardines.

This is part of a series of articles being posted on the website of the Hellenic American Leadership Council Hellenicleaders.com, a prominent forward thinking organization promoting Hellenism through civic leadership.