Last week, something historic quietly happened in Costa Rica. After a lengthy uphill political and legislative battle lasting nearly 10 years, a bill that few in the outside world have ever heard of was finally signed into law by outgoing Costa Rican president Laura Chinchilla. This tenuous victory is but the latest chapter in the trials and tribulations of the oft forgotten Afro-Descendant minorities that make their home on the shores of the Caribbean Sea.

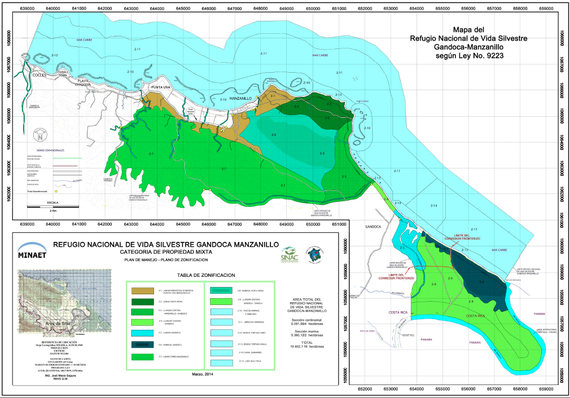

Law 9223, Recognition of the Rights of Inhabitants of the South Caribbean, does something apparently quite simple: It removes several long-standing coastal communities occupying some 900 acres along Costa Rica's southern Caribbean coast from the confines of the Gandoca-Manzanillo National Wildlife Refuge.

The very idea of subtracting land from a conservation area was the cause of strong opposition in the distant capital of San José, by environmentalists and political activists who see this change as a significant threat to the nation's conservation policy. In a country where environmental resources and eco-tourism have been central to economic development policy since "conservation" first came into the global vernacular in the 1970s, these actors were able to paralyze the poorer and mainly ethnic minority Talamancan population from pursuing their small-scale local development.

Tourism (in particular, eco-tourism) has been a major driver of economic growth and prosperity for Costa Rica for decades. From 1988 to 2012, annual visitors to Costa Rica increased by over 700 percent, with over 2.3 million visitors in 2012 and receipts exceeding $2.4 billion. And they are not coming for the casinos; in 2006, over half of all international visitors stopped by at least one national park. In other words, conservation policy has been serious economic policy for a long time now in Costa Rica.

Part of this impressive growth was possible by incredibly progressive and decisive government actions to protect 25% of land for conservation of Costa Rica's astounding biodiversity. At the United Nations 1992 Conference on the Environment and Development (the Rio Conference) and at the 2002 UN World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, as well as countless other international fora, Costa Rica is presented as the very avatar of sustainable development.

Indeed, the Gandoca-Manzanillo National Wildlife Refuge is a part of this story. A protected area of mixed land ownership and participatory management and well-planned zoning scheme, experts came from across the globe to learn what a successful community-based resource management and sustainable development model looked like on the ground.

And it looked great. While the Pacific coast of Costa Rica was turning into a playground for foreign corporations, studded with resorts and big-box hotels, the southern Caribbean coast appeared to be everything that the Rio Declaration envisioned as possible for sustainable development: a low-impact, increasingly diverse local community living in relative harmony with and responsible for the wellbeing of local ecosystems.

Underlying the shift towards "green governance" that has driven much of Costa Rica's success was a more fundamental shift in economic and development policy occurring internationally (with particular force in Latin America), the move towards a market-oriented approach to economic development known as Neoliberalism. Neoliberalism took off in the 1980s with mandates (often imposed by the likes of the World Bank and the IMF) for developing countries to deregulate, reduce the size of the State, cut deficits, and attract foreign investment.

If social scientists and ecologists came to Gandoca-Manzanillo to marvel, bureaucrats and businessmen in San Jose and abroad were no doubt chagrined by what appeared to be a rather pathetic show of economic growth in contrast to the luxury hotels popping up on the Pacific coast. The imperative to attract foreign investment was common-sense by the time that eco-tourism was taking off in Costa Rica in the 1990s. At the same time, sustainable development was shaping into its own kind of common-sense. Costa Rica's 'green governance' became a kind of quixotic amalgam of these two competing instincts. The prerogative became "maintain biodiversity while maximizing economic growth and foreign inflows of capital."

Soon enough, in 2000s, the Gandoca-Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge went from being something that the communities living within its nearly 25,000 acres were proud stewards of, to something psychologically, economically, and socially oppressive. Through legislative and judicial chicanery, the community management plan was tossed out, and people living within this model of a dynamic community-managed refuge lost the right to live on their ancestral lands and their property interests invalidated by a distant bureaucracy.

The Talamanca coastline is itself unique in Costa Rica. During the 1700s, Afro-Descendant fisherman seasonally followed sea turtle migrations up and down the Caribbean coast and in 1828 one of these fisherman brought his family up to Cahuita Point (now Cahuita National Park) and many others of the African Diaspora followed soon after.

The region remained relatively isolated from the rest of Costa Rica for the next 150 years. This was due in large part because of the independence and self-sufficiency of these Afro-Caribbean communities living in relative harmony with their environment and the neighboring indigenous communities further inland. But it was also due to racist laws and policies meant to address what some referred to in the first half of the 20th Century as 'the Black Problem'.

But the modern world arrived soon enough. Schools and courts arrived, imposing the Spanish language on the English-speaking Afro-Caribbeans. In the late 1970s, laws that locals scarecely knew existed declared many of their homesteads illegal, but no one came to tear them down. In 1979, construction began on a road linking Talamanca to the port city of Limón. Shortly after the road, a disease called monilia devastated the chocolate plantations that were central to the local economy.

The 1980s marked the take-off of Costa Rica's Green Economy and heralded the beginning of the end of the world as the Talamancan people knew it. People who had lived off the land for generations were now told that they did not own that land. For many, what land they could lay tenuous claim to they were forced to sell to outsiders hungry to buy a plot of land or start a hotel in paradise. At the same time, conservation schemes from the capital forced people off their land, or forced them to invest what resources they had into small businesses the government later threatened to bulldoze. For many locals, competing with relatively deep-pocketed outsiders in the tourism economy that had so suddenly replaced the old world was impossible.

The Gandoca-Manzanillo National Refuge is a central part of this story.

One local nature guide I spoke to while accompanying an NGO working within the local communities in Talamanca told us, reluctantly, the story of how he had been criminally convicted in a proceeding he scarcely understood simply for building a few bungalows on what he believed to be his own property. The monkeys have more rights than we do, he remarked, with a comparison that is well-worn in these parts.

We interviewed three older community leaders about the situation in Talamanca and the decades-long struggle that has made up these mens' adult lives. One of them noted that this modern world of tourism and globalization was the second best choice, the first choice now receding in memory. For the Afro-Caribbeans of Talamanca, one cannot but wonder what Costa Rica sees as their part in the eco-tourism future of their homeland.

A baker in Manzanillo demonstrates traditional baking techniques but has a demolition notice for her land standing between her and participation in the "green economy." Photo by João Cabrita Silva.

The United Nations and other international organizations have remarked that Afro-Descendants have long been rendered invisible. The irony in Central America is that, while international and domestic pressure has led to Afro-Descendants finally having their rights, their history, and their culture recognized in countries like Columbia, the reputation that Costa Rica has earned since it reinvented itself as the model of Green Governance has insulated it from the same pressures and allowed it to systematically discriminate and disrupt the lives of its own vibrant Afro-Descendant communities.

This week, Afro-Descendants and their neighbors on Costa Rica's southern Caribbean shores have reason to celebrate. By removing these communities from the Gandoca-Manzanillo National Refuge, Costa Rica's government has signaled its willingness to stop greenwashing decades of systematic discrimination and to recognize the property rights of a minority community grappling with the radical changes brought on by the forces of globalization.

Amid the clamor of a presidential run-off election this week, few likely noticed one of Costa Rica's outgoing president's last acts: the signing of Law 9223. But it is a major turning point for the people of Talamanca, who may begin the long road of vindicating their own property rights and seizing their own futures. However, the road is far from clear and there are intimationsthat the president elect, Luis Guillermo Solís, may have little intention of giving legal property title to the residents of Talamanca. And in Costa Rica's vision of sustainable Green Governance, the property rights of minority citizens are weighed against a carbon credit lost, a distant investor spending their money elsewhere.