The last figures on the cholera epidemic indicate over 11,000 cases and 724 deaths. The mortality rate is approaching 7 percent, up from 6 percent a few days ago. As you read this, the figures are most likely outdated and just plain wrong, since the epidemic is growing exponentially. Factor in the observation that reporting from rural areas is non-existent and it becomes clear that Haiti is facing an uncontained crisis. If you want to watch the spread of cholera in Haiti on a map, look at the Pan American Health Organization's tracking tool here.

The red indicator is bleeding across the screen in a graphic that resembles a horror movie.

Government statistics are also lagging, but they can be found here.

Chatter on Twitter and Google paints a picture of a totally broken health care system, and demonstrates malfeasance in planning for an epidemic after the January 2010 earthquake claimed up to 300,000.

Here is a World Share report from Twitter:

Cholera now hits the island of La Gonave, Haiti. The only functioning hospital on the island is filled to capacity. There is insufficient medical staff to treat those affected. Newborn babies and their mothers are dying.

Here is another from a Google Group:

The situation at the other Limbe hospital (Government hospital St. Jean) was worse. We brought a patient there only to discover a huge tent and no one attending a building full of patients. There was no doctor or nurse present, dry IV bags, and when we asked how a doctor could be reached no one really knew. Staff have been overwhelmed and they are looking for nurses. I think that things are not great at the hospital (St. Michel) or at the gymnasium where they are putting the suspect cholera cases. I had thought that MSF (Doctors Without Borders) was all set up, but they still won't be for a couple of days apparently.

There are hundreds of similar reports on social networking sites.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reports "a need for medical staff with more experience, additional medical supplies, including at least 1,200 body bags" in Artibonite--the center of the outbreak.

Lack of sanitation and at least 1.3 million living under plastic sheeting and tarps in ill-named "tent" cities created an environment ripe for the outbreak of diarrheal disease. Cholera, which has not been known in Haiti for an entire generation, was unexpected, but had the government, NGO's and other "charitable" organizations properly positioned rehydration supplies throughout the country in anticipation of an outbreak of an inevitable lesser intestinal disease, part of this catastrophe could have been avoided and lives saved. Cholera is treatable with rehydration. Don't treat it, and you can die within 12 hours.

Numerous rivers and streams flow through Haiti's mountainous areas. The largest drainage system in the country is that of the Artibonite River. It is strongly suspected that the United Nations Nepalese Annapurna camp introduced cholera into the Meye River, a tributary of the Artibonite River, from a faulty septic system.

Picture Haiti as a horseshoe with the opening facing left or west. Haiti has three regions: the northern region, which includes the northern peninsula; the central region; and the southern region, which includes the southern peninsula. Four days ago, we drove through the central region from the UN compound in Mirebalais to the coastal city of St. Marc in the Artibonite region. In Haiti, these regions are called "departments." We had last been in St. Marc in March, and now wanted to track the flow of the cholera bacterium through the Artibonite River Valley to the sea. Our goal was to see how local communities and clinics were coping, and whether proper supplies were in place to deal with the epidemic.

Turn on the caption function on the lower right of the slide show and follow our journey.

As we made our way north from Port-au-Prince, and finally west from Mirebalais, fog obscured the hillsides and a light rain continued throughout most of the route. This was the remnant of Tomas, which had come and gone two days previously. The rivers and streams were flowing fast, and the Artibonite, if it had not already done so, was about to overflow its banks--spreading the cholera contagion throughout the valley--contaminating crops, water supplies and homesteads.

On the way to La Chapelle, the Creole spelling is "Lachapèl," a village in the Artibonite Department of Haiti, we found the St. Guillaume Clinic.

The only rehydration supplies the clinic had on Sunday were two boxes of infant Pedialyte. 26,500 people reside in the region. Nurse Marie Suzie Mondesir said "villagers are not making it to the hospital," and unknown numbers are dying at home. They see 30 patients per day, have no soap, and the five-gallon pail of disinfectant is filled once a day by the Red Cross. The Haitian Red Cross offered this container of bleach water for hand washing. This is the only help St. Guillaume had received since November 1.

To put this discovery in context, the Red Cross bulletin of November 8 claims:

To respond to the cholera outbreak, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (International Federation) has issued a preliminary emergency appeal for $6,000,000 to assist 345,000 people in Haiti and 150,000 people in the Dominican Republic. The American Red Cross continues to respond to the cholera outbreak, most recently providing $500,000 to support the global Red Cross response, as well as purchasing 250,000 sachets of oral rehydration solution.

Where is the money previously donated immediately after the earthquake? Where are the purchased supplies and rehydration solutions?

The roads in the central region are in perfect condition with no earthquake damage and little to no traffic. There is no excuse for not getting supplies to these people.

Meanwhile the International Red Cross says it is printing "100,000 informational brochures to be distributed in camps and communities. 160-180 hygiene promoters are verbally disseminating hygiene messages and distributing soap in the capital."

Haiti does not need brochures. The 180 "hygiene promotors" are a little late, and instead of delivering soap, they should be put to work delivering emergency medical supplies to the countryside. Is the Red Cross is focusing on publicity in Port-au-Prince, where international media congregates to gather photos of the suffering in what has become known as "disaster porn" in Haitian circles? CNN has just issued a request for photos from Haiti, and what they are looking for are photos of the sick and dying. Media hardly ever sends the cameras to the central plateau, and the Red Cross and other NGOs know this. Put the logo and put the brochures where they will get the most bang of publicity for the buck.

Our next stop was the world-renowned Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Deschapelles. The sprawling grounds are located on an old banana plantation and the staff is predominately Haitian, serving a community of 300,000.

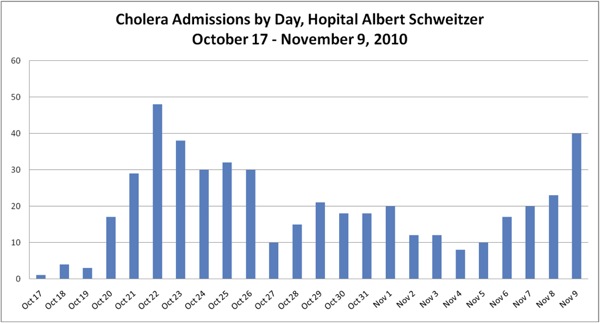

We spoke by phone with Hospital Director Sylvia Ernst who told us on Sunday, November 6, that things had stabilized and that there was no increase in the numbers of patients. They had treated 300 since the beginning of the outbreak, two week previous. By November 9, admissions had doubled after the Artibonite River overflowed its banks.

Still, the hospital was functioning and was well supplied when we were there. Ernst said we could call her any time for updates.

Cholera trends at Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Artibonite Department

Cholera trends at Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Artibonite Department

The scene in St. Marc at St. Nicholas Hospital was far different. Anger, despair and confusion were obvious consequences of an epidemic that was having its way with an impoverished population, compounded by the imperious attitude of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) toward the local population. Look at the Internet and you will find that MSF is dominating in the arena of publicity about themselves. If they are doing such a good job, why are the Haitians so angry with them? MSF's own website says that a demonstration at a cholera treatment center in St. Marc on October 26 resulted in angry crowds burning tents within the compound.

The Haitians will tell you that they did not want their town to become a refugee camp for cholera victims. Sanitation was already terrible. What about the increased medical waste? What about the possibility of disease being spread within their community?

The subtext in the MSF field report suggests that the Haitians are to blame for their own misery, especially by "disrupting efforts to prevent the spread of cholera."

From an AP report of the incident:

U.N. peacekeepers from Argentina arrived with riot shields to reinforce police. Warning shots were heard; the U.N. said its soldiers fired blanks. There were no reports of injuries.

Haitian health officials assured the crowd the clinic would not open in that neighborhood. Doctors Without Borders-Spain country chief Francisco Otero said the medical aid group would try to reopen it in another part of St. Marc.

The French and Spanish are masters at blaming the victims. The French have done it expertly in central Africa, and I personally have witnessed this same imperious attitude in Congo. Given the attitude of MSF to the local population and refusal to communicate with independent media attempting to document this story, Haitian anger is understandable. This observation does not take into account the deplorable history of both the French and Spanish in Haiti.

Adding insult to injury the UN, responsible for the outbreak that began in Mirebalais, fired on the crowd with "blanks."

Still, we wanted to try to get some answers and see how the doctors were doing. Not everyone associated with an organization is responsible for its poor leadership.

Campaign flyers for candidates in the upcoming November election plastered the front gate of St. Nicholas Hospital. A dirty litter used to transport the sick was abandoned near the wheel of a motorbike. There are no ambulances, and many patients are transported by litters and stretchers on foot, or in the case of long distance, by motorcycle.

Ward at St. Nicholas Hospital

Ward at St. Nicholas Hospital

We made our way inside the grounds and after a few camera shots to establish location; we put the lens cap back on the Nikon where it belonged. The people here did not need a camera's intrusion into their suffering. We can demonstrate in words that cholera is a terrible way to die and an incomprehensible illness to endure. It is enough to see three men carrying an unconscious young boy with sunken eyes and head listing hopelessly out of alignment with his spine. It is horrible to remember an old woman, covered in vomit and her own excrement, borne on a dirty green canvas stretcher into the bowels of the ward. It is disgusting to see family members carrying gallon after gallon of body fluids in a kaleidoscope of brightly colored five-gallon pails to a disposal site in back of the hospital. The procession of pails and people was endless.

Some pathways on the hospital grounds were awash in mud, with cement blocks forming a precarious walkway. Most people gave up trying to balance on the blocks and sloshed through the mud, bringing it into the wards. We managed to stay out of the mud in a mostly futile attempt to stay clean.

In what appeared to be the main treatment ward, a woman doctor working for Partners in Health under MSF wanted to talk with us, but said she was under a gag order from MSF, and thus, could not. The patient cots were almost touching, were covered in contaminated bedding, and family members juggled buckets of feces and vomit as they attempted to nurse loved ones.

The doctor gave us the phone number of "Carlos the Coordinaor," whose job it was to direct the flow of information. We located MSF's Carlos, who told us he was "too busy," and that we should contact the MSF press agent "Richard" in Port-au-Prince, or Cisco Otero. We reached Otero and he insisted that only the elusive "Richard" could give us the facts and figures about patient flow and numbers. We tried for two days to contact "Richard," and even called Otero again. During this process, it was easy to understand how frustrated the Haitians of St. Marc must feel. MSF was behaving in a secretive, imperious, colonialist manner towards the Haitian people, as well as myself and the Haitian man who was assisting me. I'll leave it at that.

Since we could not get "official" counts on numbers or death counts from MSF, we decided to explore the grounds. Where were the contaminated buckets of medical waste and bedding going? Behind the hospital, we found a truck loaded with grey plastic bags some of which were already punctured. Abandoned colored pails were scattered nearby. This is the disposition site for medical waste. It is put into plastic bags and loaded onto a truck--destination unknown. There are no medical waste incinerators in Haiti. What happens when this truck goes down the road, bags are broken, and liquid matter drains out along the way?

We once again to contact "Richard," the MSF press coordinator, to find some answers. He never answered the phone and did not return our calls. We left a number and are still waiting.

Discouraged by the lack of information forthcoming from MSF, we continued south along Highway One.

Cubans in Solidarity with Haitians

Cubans in Solidarity with Haitians

We had not traveled very far when we saw a Cuban flag hanging beside the Haitian flag on the outside of a building in the community of Kalfou Boua. Kafou means "corner" in English, and the building sits next to a highway intersection.

An exhausted Dr. Iliuska Sanchez of the Cuban Brigade

An exhausted Dr. Iliuska Sanchez of the Cuban Brigade

Dr. Iliuska Sanchez looked completely exhaused, but she welcomed our questions and her associate, Dr. Alexander Perez, opened his handwritten spreadsheet, urging that we photograph it. The Cubans had carefully documented the numbers, dates and ages of the cholera victims and were very proud of the fact that not one patient had died. Were they well supplied? The answer was "yes."

The attitude of the Cuban contingent, and their willingness to share information, was in very strong contrast to that of MSF.

In fact, there are several international institutions such as PAHO and the CDC, who are advising the Haitian Ministry of Health, but the lead role, although you don't hear about it in the mass media, is played by Cuba in close coordination with the health institution in Haiti. The Cuban Brigade, which includes 252 Cubans and Haitians who were trained in Cuba, is composed of 118 doctors, 78 nurses, 56 others including technicians, lab, and engineers working in Artibonite. Read about it on the Ezili Danto Open Salon blog.

So, after a very long day, filled with hope, despair and frustration, we headed back to Port-au-Prince. The Cuban doctors provided the hope that there was a group of doctors who were open and forthcoming about the epidemic, and more importantly, working in solidarity with the Haitian people. The experience with MSF was totally frustrating. The Albert Schweitzer Clinic offered transparency and communication, and the tiny clinic of St. Guillaume was the poster child for the rural crisis.

As we navigated the garbage-strewn streets of Port-au-Prince and Cite Soleil once more, the situation looked hopeless. We wondered if cholera had already infiltrated the slums. It had, but we did not know this last Sunday. The report was official this week that cholera is in the city--a terrible scenario.

PAHO Deputy Director Jon K. Andrus compared the Haiti epidemic that appeared on October 19 to the one registered in 1991 in Peru, and said everything points to a "crashing increase" of the contagion.

Andrus said that the Peru epidemic of 1991 spread to 16 countries and caused, just in Peru, over 650,000 cases in six years. With a proportional adjustment to the size of the population, a model of a similar contagion "could produce over 270,000 cases in Haiti."

Cholera, as of November 11, 2010, has reached Port-au-Prince.

The first portion of U.S. reconstruction money for Haiti is finally its way more than seven months after it was promised. The U.S. government will transfer $120 million -- about one-tenth of the total of nearly $800 million pledged from an authorization bill blocked by Senator Tom Coburn of Oklahoma.

Will it do any good?

In FY 2010, USAID provided $1,147,815 to purchase and pre-position commodities in Haiti for the 2010 hurricane season. (Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (FY) 2011 November 10, 2010)

This does not take into account the millions collected by private charities and NGOs that have not benefited the people of Haiti.

It is eleven months since the January earthquake, and the streets are still filled with garbage and rubble, the camps are filthy, and cholera will ultimately have its way.

.