The images above appeared as print advertisements in the 1950s and 1960s, which Hank Willis Thomas "unbranded," removing all text and logos to reveal the message underneath.

When we digest a printed advertisement, whether it's for a skin cream or an underwear brand or a fast food joint, the actual commercial good being plugged is often irrelevant. Behind the logo, messages such as this is how you want to look and this is how you want to be seen bubble beneath the surface, instructing us all how to look, act and speak in order to be accepted, valued, loved.

For the past decade, conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas has been fascinated with the rhetoric of ads, how they sell not just products, but desires, stereotypes and dreams. It wasn't long before Thomas realized that the true message of advertisements was not in the text or the logos boosting a product -- so, he erased them, letting the not-so-latent subtexts come to the foreground.

"I've always been interested in the power that advertising has on language," Thomas explained to The Huffington Post. "We read them before we're even aware that we saw them, because most of us now are immediately literate. I first was making works that looked like ads, and then started to realize maybe truth was better than fiction. So I actually use real ads as a way to talk about how advertisements shape our notions of reality, our notions of ourselves and especially our notions of others."

The Breakfast Belle, 1915/2015 digital chromogenic print 48 7/8 x 40 inches paper size 50 x 41 x 1 3/4 inches (framed)

Thomas, a 39-year-old New York-based African-American artist, first delved into the archives of ads with a project entitled "Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America," in which he examined how race can become a branding strategy. In an interview with his mother, photographer Deborah Willis, Thomas explains: "I always like to stress that the craziest thing about blackness is that black people never had much to do with actually creating it. It was actually created with commercial interest in order to turn people into property. The colonialists had to come up with a subhuman brand of person and that marketing campaign was race."

For the project, Thomas collected advertisements printed between 1968 and 2008 -- coincidentally, Thomas noted, the years between Martin Luther King's assassination and Barack Obama's election. He selected one ad per year, one he felt accurately captured the atmosphere of mainstream society at the time, and then, he "unbranded" them, removing all texts and logos from the ads. "They become naked in a way," he said. "You're looking at what's really being sold. The message that's sometimes being hidden by the logo and the copy."

In his upcoming exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery, "Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015," Thomas directs his attention towards the evolution of the mythical white woman, packaged and sold by advertisements throughout the past hundred years. She's precious, she's innocent, she's privileged, she's pure -- and yet she's disenfranchised and oppressed.

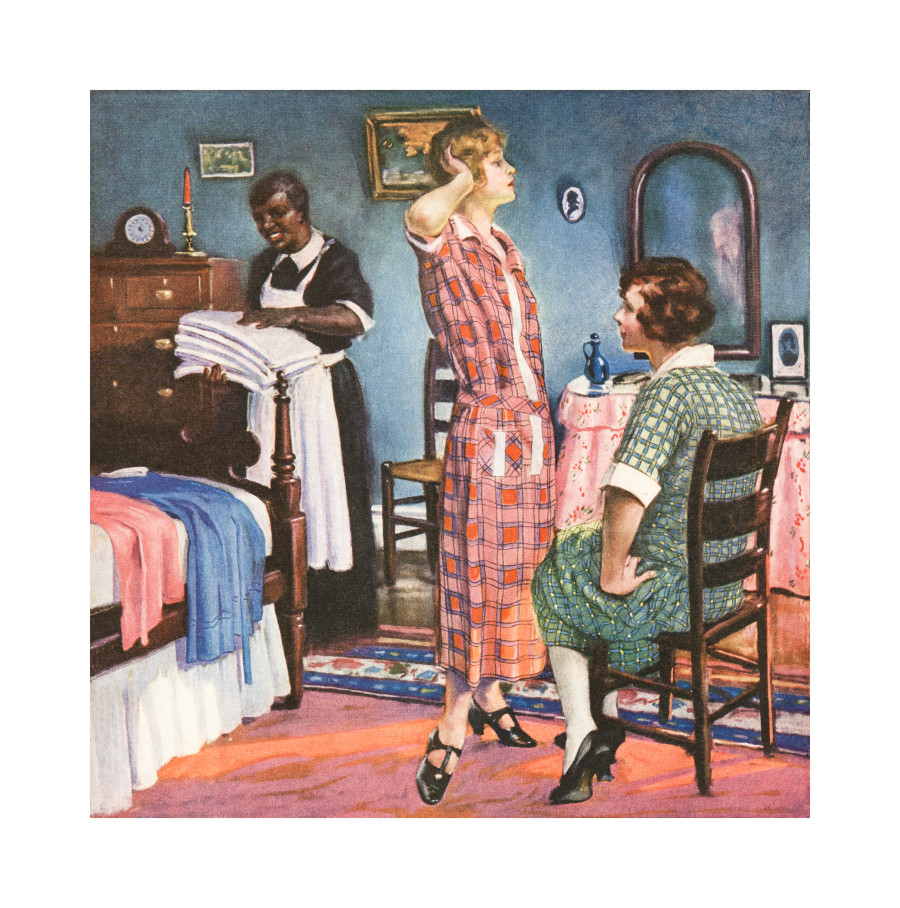

There ain’t nothin’ I can do nor nothin’ I can say, 1924/2015 digital chromogenic print (framed)

"Whiteness is something I'm fascinated with because it's ever evolving," Thomas explained. "One hundred years ago a lot of people we call white today would not be considered white. And also, a hundred years ago women in the U.S. didn't have the right to vote. And, even though African American men technically did, everything was done to make sure they didn't. I'm interested in how white women -- who are often seen as the most valuable -- are at the same time marginalized."

While Thomas' 2008 exploration of blackness in advertising coincided with the election of President Obama, his current exhibition conveniently overlaps with the looming potential election of a female president. "In the last presidential cycle, there was this whole debate where people were going back and forth between Hillary [Clinton] and Obama, questioning are you more racist or more sexist? That's a way of dumbing it down, obviously. But I realize that we might be on the verge of having our first female president, a white woman," he said. "I want to look at how someone like her might have been looked at or treated or spoken to back then, and today."

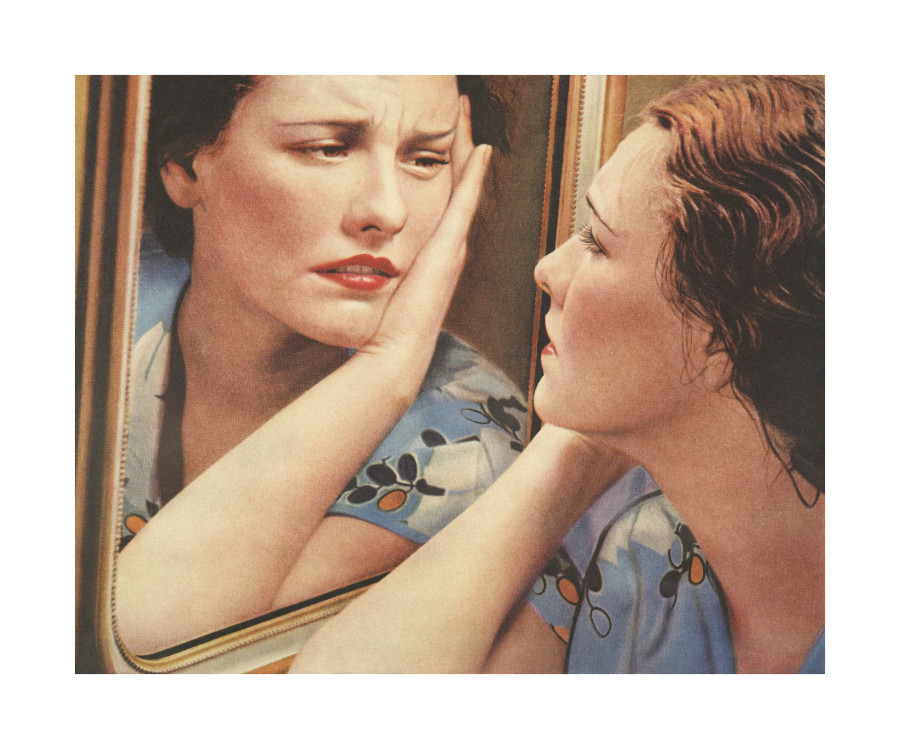

Wipe away the years, 1932/2015

Over the course of a year and a half, Thomas pored over hundreds of vintage advertisements. In an ad from 1924, two flapper-esque ladies romp before a vanity mirror while a black maid, smiling, transports folded sheets. The original slogan, which Thomas erased, read, "How To Make Even Ordinary Cotton Goods Look And Feel Like Linen." Thomas notes the transition of black women's roles in white women's advertisements as time progresses, from subordinate to equal. Another ad, from 1963, depicts a smiling woman coolly holding a cigarette, toting a black eye. "Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!" the caption cheerily reads. Without it, the sunny image of docile domestic abuse is spine-chilling.

"When you market towards any demographic, you have to be prejudiced," Thomas explained.

Home front, 1943/2015digital chromogenic print

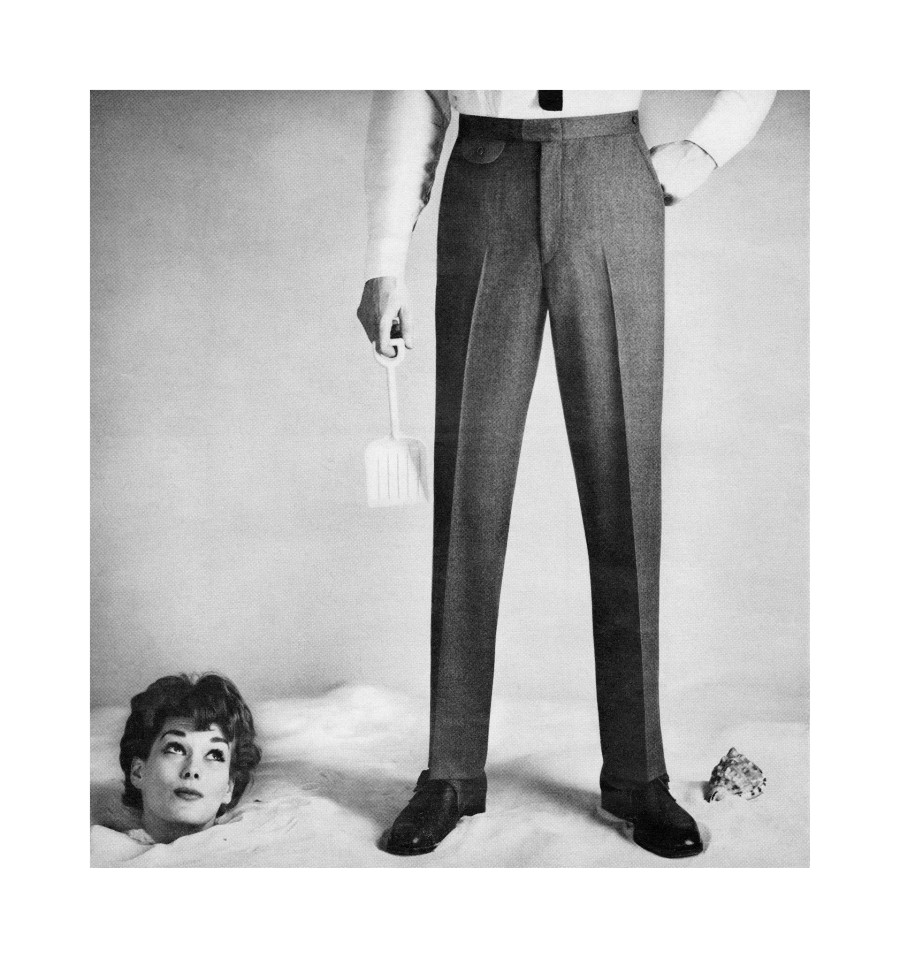

As the years progress, you can see the gradual evolution of the fictional "white woman," as she slowly becomes sexualized in the '20s, temporarily empowered during World War II, violently punished in the years that follow. "In a way, the project unfolds like a narrative. You're watching this character through the times," Thomas noted. Aside from depicting the changes in white femininity, the image cycle also traces the rise and fall of print advertising itself. "When the project started in 1915, print advertising and especially photography were very new. Graphic design and images were having a revolutionary moment. By the '30s and '40s, you can tell advertisers and graphic designers had kind of figured out something." He continued:

And with the golden age of advertising -- which is kind of what Mad Men is about -- you see this intense pushback about putting a woman in her place. And at the same time, more and more women are getting places in the board room or are at least taking part in the conversation, so there's progress in that sense. For every two or three sexist images you'll find one that's somewhat progressive. But then again, something that's seen as progressive at the time may seem marginalizing and sexist today. That's something I think is interesting. In trying to read this images, it's almost like you have to go into a time machine to really understand what it was like for the people seeing these for the first time.

The cycle wraps up in 2015, ending with a Ram advertisement riffing off Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze's 1851 painting "Washington Crossing the Delaware," with a lot of women in bikinis on top. Despite the slightly disheartening finale, other images -- such as 2014's Tylenol ad featuring a lesbian couple taking a selfie -- show just how far we've come. "One thing I can say definitively is that it's much more complicated and diverse now than it was 100 years ago," Thomas said. "Now you see the same sex couples, the over-sexualized people, the family person, the business person. It's much more diluted than it once was."

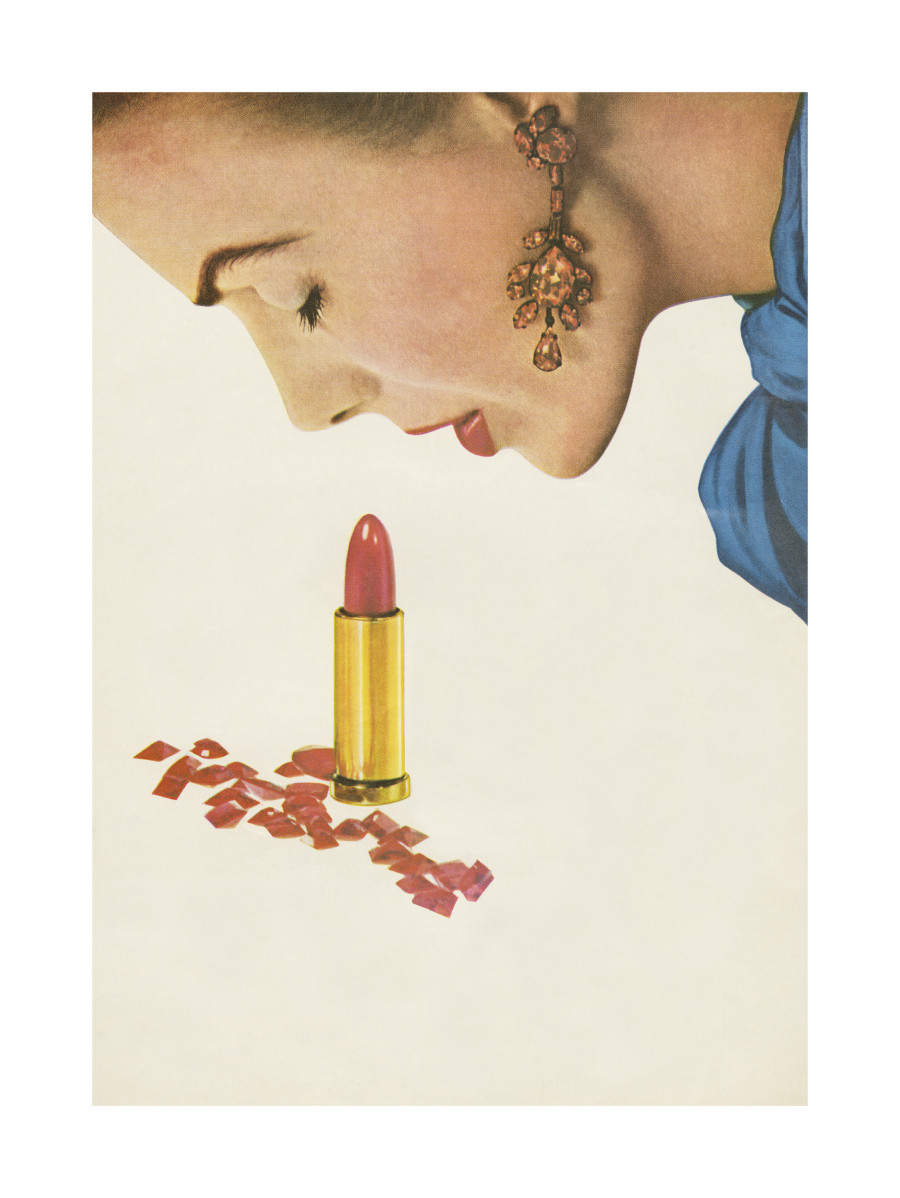

Will not go dull and lifeless, 1953/2015 digital chromogenic print

As a whole, Thomas' series presents a fascinating and haunting narrative of the "white woman," from buttoned-up Gibson girl to bikini-clad Revolutionary war biddies. Thomas identifies at least one thread connecting the disparate imagery. "They say: if you want to be valued or respected or cared for, you have to look this way."

"Most people of color are very used to society not respecting them for any number of reasons. But there is also this huge population of white women who will never fit into the standards of value that society has created," Thomas said. A second unifying factor, we would add, is that the goods being publicized are often impossible to determine. What's really being sold is something far more convoluted.

Using printed archives as his medium, Thomas has developed an unorthodox artistic process that works to ensure our past belief systems and accepted behaviors are not easily forgotten. "I like to think of myself as a visual culture archeologist, or a DJ," explained Thomas. "I'm using these materials that have been discarded or forgotten, and am trying to elevate them to give them new life, new conversation and new purpose, that speaks to the original mission of selling a product. It's interesting because you can rarely tell what the original product was for. The image and the product rarely have anything in common."

Good thing he kept his head, 1962/2015 digital chromogenic print paper size

For a future project, Thomas mentions digging into the archives of South Africa under apartheid, exploring how ads marketed to black and white individuals. "I think ads are very much a reflection of the hopes and dreams of a culture at a particular moment in time," he said, "and that's why they're so powerful and potent as historical documents and artistic works."

At the close of his artistic investigation, Thomas hesitates to provide any all-encompassing summary to the depiction of "white woman" manufactured and honed in the United States over time. "I learn as much from what other people have to say about it as what I have to say about it. I guess I would sum it up by saying the work is not really about white women, it's about people," he said. "How people are put into a group and how complicated and ever-evolving the notions of club membership and authenticity in the group are. It's weird to look at 'white women' and see this."

It certainly is.

Aggressive loyalty, 1963/2015 digital chromogenic print

"Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015" runs from from April 10 until May 23 at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York.

Related

Before You Go