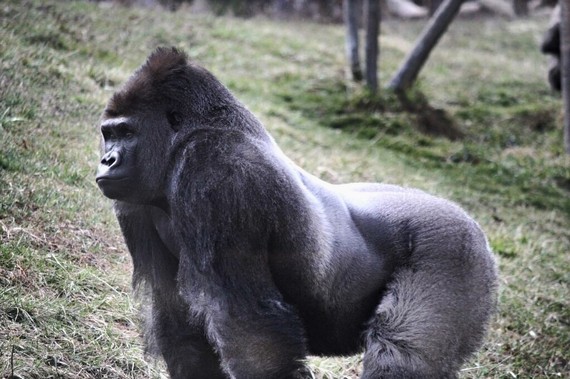

It's ironic that the shooting death of Harambe, a western lowland gorilla at the Cincinnati Zoo, has sparked a debate over zoos. It's odd because: 1) Zoo shootings are so exceptionally rare that most zoos will never face any event calling for a gun, 2) Therefore, everyday conditions at zoos -- not exceptional tragic events -- are more appropriate reason to reconsider zoos' role, 3) Shooting deaths of free-living animals are rampant, constant and institutionalized, 4) Domestic animals in the food system live incomparably more miserable lives than animals in zoos who usually are, at worst, securely bored, 5) Yet, many people appalled by Harambe's death still buy meat, cheese, eggs, leather and so on -- proving that we tend to be used to what we're used to, so we miss various forests because we love trees.

Before going further, I'd hasten to say that I do not think that Harambe had to be killed. Harambe lived amidst humans his whole life and knew what the boy was. To me, there seemed time to tranquilize Harambe. As in two non-fatal incidents where kids fell into gorilla enclosures, Harambe's behavior suggested no intent of harm. If Harambe had no interest in harming -- he had no motive for harm -- then the child's life was not in danger. The most certain thing we know is that Harambe's death resulted from erring on the side of caution for the boy. Most humans value human life above other life. Certainly a dead child is more of a problem for a zoo than a dead gorilla, and the surviving gorillas cannot sue. We'll never know.

It's a quirk of human perception that the full shock of our dysfunctional relationship with the living world usually occurs to us only momentarily through bright but isolated events. We have trouble grasping or dealing with the bigger trend. Free-living gorillas are shot so their infants can be sold on the black market, yet the universally unwanted death of zoo-born Harambe during a freak incident becomes the focus of an intense debate over the very existence of zoos. Rightly shocked by the killing of Harambe, we ignore the human expansion, habitat destruction, trapping, and poaching that have put his kind within hailing distance of total annihilation from the world. Rightly shocked by the cruel and stupid "sport" of an American dentist shooting arrows into Cecil the lion, almost no one attends to the fact that free-living lions have declined about 75 percent in the last 50 years under continual lethal pressure from expanding villages, herders, and poachers. If you think there's nothing you can do about the existential threats facing these creatures, there's news for you. Search for "gorilla conservation" and have your checkbook handy.

Being a wild gorilla is far more dangerous than being a zoo-born gorilla. Yet the wild is the only slim hope of true survival; zoos are dead-ends for creatures whose dismantled native habitat makes reintroduction impossible.

Apes in zoos are not "endangered" in quite the same way free-living animals are endangered. In zoos, they're already gone. The reason they're endangered is that their habitat is too demolished or they're being hunted to extinction. There's nowhere to release a zoo-born gorilla. They are not part of the viable living world. They hang on in a weird and unnatural limbo, wholly dependent each day on the one creature who is the source of all their problems. And yet zoos, too--or at least captive populations -- may become the remaining wafer of hope when the final free gorilla takes their last gasp. We have put them in terrible times, when even solutions can seem at odds with each other.

Zoos or nature? That's not the choice. Nature or no nature is a choice, and the broad trend is that we are choosing no nature. This will not be to our advantage in the long run; in the short run it's simply a catastrophe for billions of living things.

The welfare of creatures living in zoos is important, both for zoos and as it reflects how much a society cares for kindness. But zoos are almost literally a sideshow. Survival of the living world itself, the conservation of nature -- species in viable populations, functioning relationships on interdependent species, habitats, and natural systems -- is incomparably more important than zoos. So much more that most people can't grasp it, or get overwhelmed, and turn away. Even on a strictly humane level there's way more at stake outside zoo cages, where humans make life deadly dangerous for animals, than inside where humans make life merely predictable and dull -- unless a kid falls in.

Zoos or no zoos is a question we can debate, but life is never that simple and zoos do not correspond easily to simplistic questions such as: are zoos justifiable?; are zoos ethical or not ethical?

There are better zoos and worse zoos. There are animals better suited than others to captivity. (We adopted two captive-born parrots who often perch on their cage when we leave it open all day; it's home to them.) When I was a little child the great ape and big-cat houses were jails, entirely concrete so they could be hosed off, with big bars. No one seemed to be thinking of naturalistic habitats, social groupings, play, psychological well-being, or the range of natural motions. Now, at some zoos, even the size and texture of food is considered, so that big cats can employ their whiskers and bring a fuller range of senses into play. Much has changed for the better.

What are the reasons for captivity of wild animals? Basically three: entertainment, education, and conservation. Conservation could be served on naturalistic sanctuaries without public viewing and often without public funding, and in purely wildlife-research focused facilities supported by government funding, such as the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center and others. The best zoos, such as those run by the Wildlife Conservation Society, serve a wider conservation mission using a combination of paying zoo visitors and grants to run their public zoos and global conservation projects. I see no compelling reason not to pursue both.

As a city child, going to the zoo or aquarium was a window on a realer, bigger world populated by wondrous creatures. Locking eyes with an ape or eagle can be life-changing. It was for me.

That's why I'm not against zoos; I'm against bad zoos. Zoos must serve their animals both in their enclosures and in the wider world. When animals of the wider world serve zoos, there's a problem. And there is. Zoos, especially in Europe and the U.S., have a much larger proportion of captive-born than wild-caught animals than ever. But overall, zoos still take more animals from natural populations than they reintroduce to help natural populations recover. There have been notable exceptions where zoos bred endangered animals for successful reintroduction to the wild, perhaps the best being zoos' role in saving the California Condor and Golden Lion Tamarin monkey from extinction, and being the driving source for their recovery. That's ideal. There is no longer adequate justification for taking whales and dolphins, elephants and apes, out of their wild homes so we can gawk at them. Yet it's still being done. I am against it. Wild-caught elephants are still being shipped to zoos in the U.S.; I'm against that. I am against killer whale captivity.

Why are gorillas even in zoos? Reasons high and low. Because they reflect us. Because they are beautiful. Because they make money for their captors. Because we are curious. Too curious for our own good and theirs, sometimes. Harambe was in captivity because he was born there. The only option in his case was his non-existence. This has now been granted him by the powers that be.

Meanwhile, all the big animals that people most care about are at their lowest free-living populations ever. No one can do everything, but everyone can do something. Please do.

# # #

Carl Safina's most recent book, Beyond Words; What Animals Think and Feel, will appear in paperback in July.