Black America doesn't have leaders. The Black Lives Matter Movement lacks leadership and clear demands. Whether voiced as lamentations from within Black communities or discharged as critiques from without, these claims are so oft-repeated that they've almost become platitudes.

As commonplace as these charges, are responding thought pieces, which suggest that African Americans are no longer looking for heroes, explore the decentralization of Black leadership in the post-Civil Rights era, and critique or defend the structure of BLM.

This is not one of those pieces. Here, you will not find a recap of how Black statesmen eclipsed Black women's significant contributions to the struggles for civil rights (although that is true). Nor will you find a defense of BLM's decentralized constellation, arguing that because it amplifies the voices of women and LGBT folks, it offers an antidote to the sexism and homophobia that stifled those voices during the Civil Rights Movement (also true). Instead, let's consider these questions: Who are your Black leaders? What does leadership look like to you? How can educators, parents, political representatives, and other concerned individuals support the future generation of Black leaders?

As an Africana Studies professor who has spent my career working with Black youth, my answers to these questions might be surprising. I believe the answers rest, in part, in recognizing the agency and power of millennials who have broken the old school mold. I become incensed when commentators accuse contemporary youth-led organizations of lacking leadership, respectability, and clear demands. Such critics also bemoan that youth activists shut out veterans like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. My response? There were ideological differences between the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Martin Luther King, Jr. SNCC, shepherded by young organizers such as John Lewis and Diane Nash, were the upstarts who demanded change in bus terminals and at lunch counters. As "respectable" as their Sunday best outfits appear to us in the black and white photos of that era, getting arrested garnered disapproval from many of their families--Nash's grandmother told her, "Diane, you've gotten in with the wrong bunch." These youngsters pushed social barriers in ways that made older folks cringe in order to expose the injustices of segregation. That's what made them leaders.

Today, my Black leaders tend to be of the same ilk. I count Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors, the Founders of #BlackLivesMatter, as leaders. For raising awareness about the murders of trans women, I regard Laverne Cox and Janet Mock as guiding voices. When, in the wake of the murders of nine Black people at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina, Bree Newsome removed the Confederate Flag from the State Capitol grounds, she became a champion. Then sixteen-year-old Amandla Stenberg's use of Instagram to school her peers in the intersectional oppressions Black women face, positioned her as a firebrand. For enlisting over 100,000 immigrant youth to fight for citizenship, I claim United We Dream as crusaders. And I count as standard-bearers the University of Missouri student activists whose protests against campus racism led their university's president to resign and sparked highly effective solidarity campaigns at colleges nationwide.

These types of Black and brown pacemakers tend to fall under the radar of the annual Black History Month commentary on the state of Black leaders. In 2013 BET commissioned a poll asking Black Americans to indicate who speaks for them. The results sparked attempts to address why 40% of those polled could not identify a spokesperson, 24% selected Al Sharpton, 11% named Jesse Jackson, and 9% chose Maxine Waters (with Ben Jealous, James E. Clyburn, Marc Morial, and Michael Steele receiving single digit acknowledgments). Of course we should all know who these people are, but imagine African American millennials' responses to these results: "Who?" Even though the poll offered a follow-up query of "Are there any others not mentioned above that you would say speak for you?" the set-up, with choices between six adult men and only one woman, defined leaders as overwhelmingly male and decidedly non-identifiable to young African Americans.

We are not socialized to think of individuals outside of politics and young people --especially young Black people--as leaders. I've challenged myself to see the problems facing Black youth from their perspectives. What I've learned is that Black youth activists are not only fighting for justice against police brutality, for immigrant rights, and for educational environments that don't undermine their human dignity, but also for the freedom to claim those rights while wearing hoodies and posting their grievances via social media. They are fighting for the liberty to express themselves as freely as their White counterparts.

Surely, the successful recent wave of student-led protests has taken a page from Civil Rights era leaders like Lewis and Nash. But with their powerful use of social media (a tactic Barack Obama wielded both in his campaigns and to promote his policies) they've also turned the page on yesterday's leadership.

Whatever our critiques of youth leaders may be, we cannot deny that they have brought national awareness to the violent disregard for Black life. And we cannot ignore that college students on campuses all over this country have risen up--many of them waving "Black Lives Matter" banners--and have compelled their administrations to address their demands. That's what leadership looks like to me.

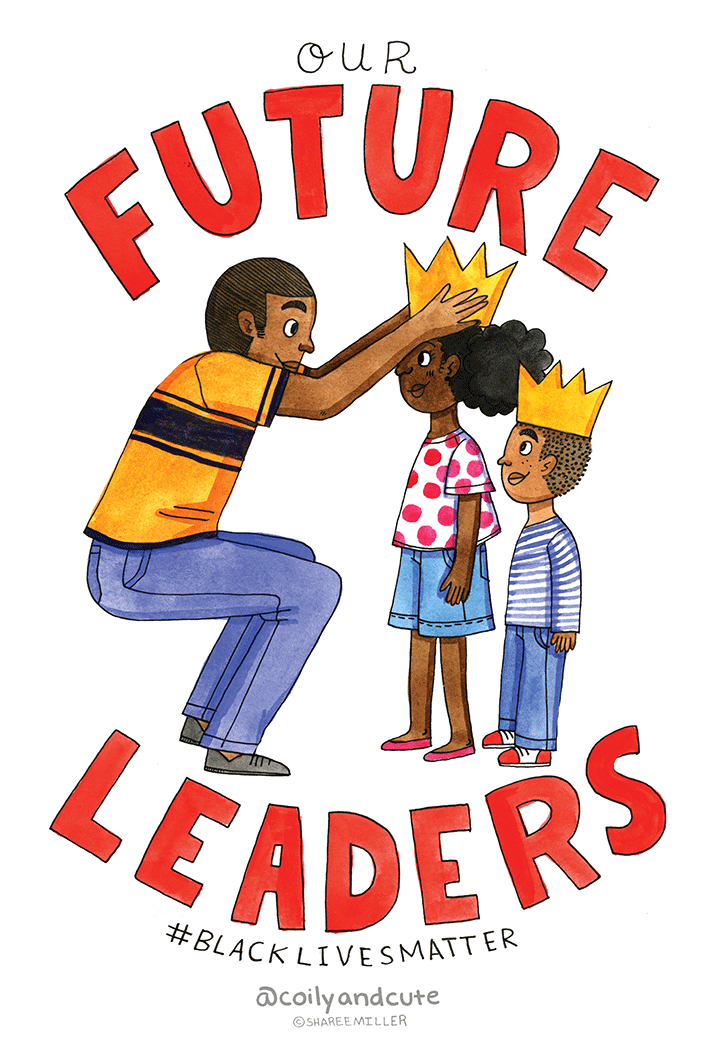

Illustration by Sharee Miller

This post is part of the "Black Future Month" series produced by The Huffington Post and Black Lives Matter Network for Black History Month. Each day in February, this series will look at one of 29 different cultural and political issues affecting Black lives, from education to criminal-justice reform. To follow the conversation on Twitter, view #BlackFutureMonth.