When I told the innkeeper that I was writing a guidebook to Hawaii, she sighed, "Why on earth do we need another one?"

We were sitting on her spotless white sofa, with a view of her grapefruit orchard webbing up a hill. A chicken, one of Kauai's many well-known residents, led her tribe of chicks past the window. The innkeeper smiled and brushed her blond hair out of her eyes before going on a rant about how guidebooks and tourists have ruined her island, one, I might add that she had moved to over 20 years ago.

My next conversation with a local brought a similar, albeit harsher, response, directing me to his website that in no uncertain terms told tourists not to bother visiting the island and if they do to, basically, go swim with the sharks. This was not how I envisioned locals to react on an island whose number one industry is tourism.

Of course, I had no false images of hot dark skinned men, wearing not much more than palm leaves, draping jasmine leis around my neck -- this is an island that has been conquered, colonized, bastardized and spit back out by more than one greedy group of intruders.

First there were the Tahitian explorers, then came Captain Cook's crew of STD-infected/gun-toting sailors. There were the missionaries, the sugar barons, the Portuguese, Japanese, Chinese, Russians, Filipinos, and then Americans. Everyone wanted (and still wants) a piece of this fertile land. And ultimately, many outsiders got their slice.

Today, most Hawaiians cannot afford the rising costs of homes on the island and many are forced to move to affordable cities in the mainland (Portland and Las Vegas are the most popular choices). The people who stay tend to work low-paying jobs (or two) in the zillions of condos, hotels, and restaurants popping up like teenage acne along the sunny South Shore of Kauai, Kona in the Big Island, or Waikiki.

But as I spent more time on the islands and began taking to more locals, I quickly realized that there was more to the issue than the frustrations of a colonized community depending on the invaders for sustenance.

After that initial "welcome," I aimed to get to the bottom of why this contradiction exists. How can a culture that depends on tourist dollars have such animosity for their benefactors? So I got introduced to Pat, who works for a state senator, and we made an appointment to have lunch at Kauai's Olympic Café -- a wildly popular open air restaurant, perched on the second floor with a view of old town Kapaa. The wooden chairs were all taken by a combination of chatty tourists and Pacific Islanders, though I noticed that none of the cultures commingled.

Pat explained that Hawaiians, in addition to being the friendliest bunch of Americans, are also the proudest. Consider the elements: the finest beaches in the United States and maybe even the world, surf spots that intrigue the sport's best, volcanoes, rainforests housing birds and plants not found elsewhere, and a language so poetic, so powerful that it can exist with less than ten consonants.

Even more, these people are survivors. As a culture, wayward in the middle of the Pacific a good 3,000 miles from the mainland, they have had to be sustainable on all fronts. From food to an influx of visitors (both friendly and hostile), the locals have learned how to take care of themselves and their community in a fix.

But, she added, that because of this rich history and fragile landscape, the people are also fiercely protective of the land. This is not something mainlanders (or at least city folk) can understand that well. If we have a dramatic waterfall, we don't blink if millions of people come view it (take Yosemite Falls in summer for instance).

Hawaiians on the other hand believe their land is sacred, that it both shields and punishes them. So what happens to their culture if they simply allow visitors to overrun a waterfall? They believe that the gods will hurt them.

There is a famous saying in Hawaii about the taro plant, that if they take care of the taro, the taro will take care of them. Mainlanders generally see botany as the other way around.

For this reason, my new friend Pat asked me not to include Kipu Falls in my guidebook. This caused an ethical dilemma for me as a writer. Every single guidebook lists this waterfall as a locally favored spot to cool off in summer. However, this is also one of the most dangerous parts of the state even though this secret swimming hole/waterfall popped up on the tourist radar and has locals reeling. Besides the fact that hiking in officially breaks the law as you cross private property to get to the falls, the physical dangers are numerous.

Locals, who know the waterfall intimately, swing into the water below on a rope swing. Tourists, misjudging the height and depth of the water, have been seriously injured here and one person even died. Ultimately it is for your safety that I recommend you swim elsewhere, and this is why I chose to honor Pat's request.

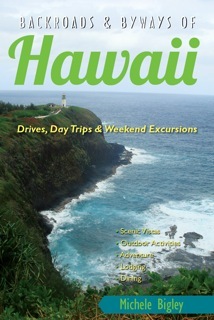

In my Backroads and Byways of Hawaii book, I excluded this waterfall, but also included ways to get here safely on a tour. I did this for multiple must-have experiences in the state throughout my new guidebook.

It seems the only way to offer a balanced perspective on Hawaii is to give readers the truth.

This book isn't about leading you to the secret spots of Hawaii, for this, you should make friends with locals. Instead, I figure that if you understand the impact, both positive and negative, of your footprint on the state, you will be a better house guest, one who is invited to return year after year.

For more on Hawaii, pick up a copy of Backroads and Byways of Hawaii.