HONOLULU - The first thing to know about the Next Step homeless shelter is that it’s hard to find.

Tucked inside a nondescript warehouse in the Honolulu neighborhood of Kakaako, it’s easy to miss if you don’t already know it’s there.

But plenty of people do know, and on any given night, scores of homeless people arrive at Next Step, looking for a spot in one of the 174 “cubicles” — each 4 feet by 6 feet.

Run by Waikiki Health, the shelter often attracts more people than it can handle.

“We sometimes have 10, 15 people outside wanting to get in,” said Richard Kaai, Next Step’s shelter services supervisor. “We have to turn them away because we don’t have any room.”

Richard Kaai, shelter services supervisor, says homeless people are not subjected to strict rules at Next Step.

Richard Kaai, shelter services supervisor, says homeless people are not subjected to strict rules at Next Step.

On the face of it, it’s not surprising that the shelter has been operating at its full capacity. Oahu, after all, is home to hundreds of homeless people who could use its services. The latest count in January found that the island had more than 1,900 unsheltered homeless people — an increase of 62.5 percent since 2009.

But Next Step is bucking a curious trend.

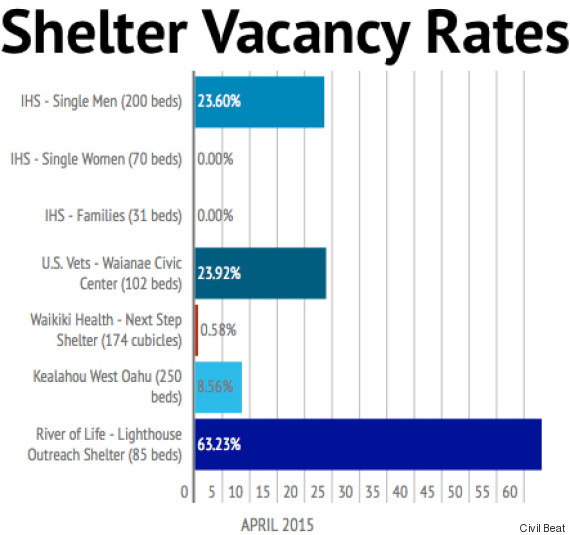

All around the island, a number of homeless shelters have been operating at well below their capacity, according to the homeless advocacy group PHOCUSED, which has been tracking the shelters’ vacancy rates since March 2014.

For instance, at a Waianae shelter operated by the U.S. Vets — a nonprofit organization serving homeless veterans — nearly 24 percent of 104 beds went unused on average in April. The vacancy rate at Lighthouse Outreach Center, a Waipahu shelter with 85 beds, was even higher: about 63 percent.

At the Institute for Human Services, the biggest homeless shelter operator in Hawaii, the facilities reserved for single women and families — with about 100 beds — are usually full, but the vacancy rate for its men’s shelter, which can house 200 people, has been hovering around 20 percent this year.

But, at Next Step, the vacancy rate hasn’t climbed above 5 percent since June 2014.

A number of homeless shelters on Oahu have been operating well below capacity, according to PHOCUSED statistics.

A number of homeless shelters on Oahu have been operating well below capacity, according to PHOCUSED statistics.

Its popularity stems in part from its location: The shelter is just a few blocks away from Kakaako’s large homeless encampment — which has ballooned since the city’s “sit-lie” ban took effect in Waikiki and other central business districts last year.

But Kaai says Next Step’s main attraction is that it doesn’t put people through the rigors of keeping up with an array of shelter rules.

“The number one thing is that we bring in anyone who’s willing to come in and treat them with compassion,” Kaai said. “We meet them where they are at. When they come here, they have a lot of issues, and we try to accommodate whatever their issues are.”

Curfews and Random Searches

Next Step’s approach, while not unprecedented, is decidedly nontraditional.

For decades, the classic model of operating shelters has been to focus on making homeless people “housing ready” with strict rules for maintaining sobriety or compliance with mental health treatment considered essential for successful transition to permanent housing.

At IHS, for instance, all newcomers are presented with a lengthy list of rules upon intake — like a 9 p.m. curfew, a requirement to open a savings account, and prohibitions against smoking, “illicit drugs,” and cutting and coloring of hair. They’re also warned that random searches could be performed.

But the classic model has a serious flaw: People who are addicted to alcohol or drugs, have severe mental health problems, or simply can’t abide by the rules of an institution — the reasons most of them are homeless in the first place — are either not allowed in or pushed back out onto the streets when they violate the rules.

Like Next Step, many shelters are veering away from the model, says Matthew Doherty, executive director of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness.

“They recognize that the critical role of shelters is to be the first point of entry toward permanent housing — but, in order to make it work, you need to remove as many barriers as you can,” Doherty said. “The conversations are happening more now, and it’s an evolving and increasing area of focus.”

The approach is a derivative of a concept known as “Housing First,” which prioritizes moving homeless people straight from the streets into permanent, supportive housing over tackling other goals — like sobriety, mental health treatment and employment — that could be attained later with the help of on-site case managers.

There are many skeptics.

Bill Hummel, program director of the Lighthouse Outreach Center, says bringing the Housing First approach to running shelters would lead to a “revolving door.”

“A part of the purposes of shelters is to help people develop behaviors that would enable them to move into and remain in permanent housing. And following the rules is part of the deal,” Hummel said.

Kimo Carvalho, director of community relations at IHS, said not every rule at his shelter is always “followed to a tee.”

“At times, there are clinical reasons why you have to make exceptions to the rule,” he said.

Still, Carvalho generally agrees with Hummel.

“The rules are actually a critical tool for getting unsheltered clients back into the system of rules, so that we can get them reacclimated into the society,” Carvalho said.

But, to Doherty, a high vacancy rate when the need is great poses a fundamental question: “If I were operating a shelter in a community with a large number of homeless people, and my beds aren’t being used, I would want to be asking myself, ‘What’s the program that we’re operating, and are we providing right interventions?’ ‘Are we providing the right opportunities for people in my community?'”

Colin Kippen, Hawaii’s state homelessness coordinator, concurs.

“Our transitional and emergency shelters here are all trying to do the best that they can, but sometimes we have to really re-evaluate how we operate in light of best information and best practices we have available in the field,” Kippen said.

Next Step’s residents can keep personal belongings in containers near their cubicles.

Next Step’s residents can keep personal belongings in containers near their cubicles.

Showing Up Drunk or High

The Downtown Emergency Service Center in Seattle has used the low-barrier approach to to running its shelters since it was founded in 1979, says Greg Jensen, the nonprofit’s director of administrative services.

“People come to our shelter basically as they are, without needing to demonstrate sobriety or compliance with any kind of treatment. We don’t have a rule about people coming in high or intoxicated,” Jensen said. “Our philosophy has always been to simply provide what people need and impose just common-sense rules of behavior.”

The approach has worked so well for DESC that it opened up a building — officially named for its address, 1811 Eastlake — in 2005 to house homeless alcoholics and allow them to drink on the premises.

It has since been widely regarded as successful because almost all residents cut their drinking significantly during their stays. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2009 found that 1811 Eastlake’s residents averaged 20 drinks a day at the time of their intake, but the number fell to 12 within two years.

The study also found that 1811 Eastlake cut the amount of money spent on trips to emergency rooms and jails. Prior to an intake, an average resident cost the city more than $4,000 a month — but only $958 a month afterward.

The result has been so striking that other cities — like New York, Chicago and Anchorage, Alaska — have opened similar “wet houses.”

“We’re just focused on the fact that people living with addictions and mental health issues aren’t going to get any better if they are living outside,” Jensen said. “If we can bring them inside, they’re closer to getting services that they need; we’d be in a better position to help them.”

Kaai says that, while Next Step doesn’t condone drinking or drug use on its premises, it doesn’t reject people for showing up drunk or high. “We just make sure that they are safe, and we make sure they go to their cubicle and sleep it off,” he said.

That tolerant stance separates Next Step from other homeless shelters on Oahu, Kaai said.

“At other places, it’s more of, ‘Do this, do that,’” Kaai said. “You do have to follow the rules here, too, but we try to work with them — instead of saying, ‘Do it, or get out.’ That seems more conducive in them trying to improve their lives.”