My cousin Justin and I are speaking to each other for the first time in a decade. He tells me about the usual things that interest ten-year-old boys: his favorite restaurants, karate class, his new haircut, and Nintendo games. I find myself enjoying our conversation and hearing about the activities that are important to him.

As we prepare to head to the park, Justin withdraws. He is visibly frustrated, sighing loudly and frowning. I ask him what's wrong. What he tells me breaks my heart.

"People at school say I'm stupid," he says to me, fighting back tears and fidgeting nervously. "People at the park say I'm stupid."

My aunt had mentioned to me that there had been an incident weeks ago, that one of Justin's classmates had teased him, but I had no idea how much it still affected him. I am torn between my sympathy for my cousin and my anger at his peers for hurting him so deeply. We all are teased as children. But for children with Autism who are unable to defend themselves with a quick comeback or a threat to tattle, being teased cuts at a deeper level.

Justin has Apraxia and does not speak. So you may be wondering how he told me about his classmates' cruelty. He found another way.

For years, Justin has been learning the Rapid Prompting™ Method of communication, developed by Soma Mukhopadhyay and taught by the Helping Autism through Learning and Outreach (HALO) non-profit organization. Using an alphabet letter board and electronic communication device, Justin spells out what he wants to say with his fingertips. Because his hand muscles are weak, he needs someone to sit with him and support his wrist, but it is Justin who does all the talking.

Until recently, Justin spelled out only words and short phrases to communicate, and only with his parents. But a few months ago, he began holding full conversations with his mother. Using the letter board, he now constructs clear, coherent, and complete sentences. Through this tool, we are learning more about Justin's personality, his sense of humor, and his emotions. He love sharing himself with us.

This is why I say that Justin and I have just spoken to each other for the very first time. For his entire life, I've been talking at him, and always getting the same responses: a wave for hello, sign language for "yes" and "no," and a kiss on the cheek whenever we said goodbye. Last weekend, as he sat beside me, I watched him move his little fingers gently from letter to letter on the board, spelling my name slowly but correctly on his first try: B-R-E-T-T.

Justin's parents, who are the most loving and patient people I have ever known, have spent years explaining that even though he is non-verbal, Justin understands everything being said around him. Those of us who know and love him have never for a second doubted his intelligence. But even my aunt was surprised when Justin, having learned that his grandmother had just passed away, said matter-of-factly, "I understand death, mommy."

Justin's communication breakthrough and good behavior have made it possible for him to attend a non-Special Education school for the first time this year. With that comes a classroom full of children without disabilities, without aides, without Autism. With that comes children who ask questions, point, stare, and laugh at what they don't understand. Justin's newfound ability to articulate himself so fully has been a major milestone in his young life; but it has also been tarnished by the hurt he feels at school.

Nothing is more painful than watching a child you love refuse to play in the park on the first warm day of spring because he is afraid of being teased. Regardless of whatever insensitive insults people toss his way, the word "stupid" is the one that Justin takes the most offense to. Rightly so, because he is smarter than most ten-year-olds without disabilities. But he is also far more sensitive.

We sit on the couch, and Justin slips his shoes off and on, clearly torn between enjoying the gorgeous weather with his family and facing being ridiculed again. Justin's big sister Melanie, who is not Autistic, offers to "beat up" anyone who calls Justin stupid. I laugh.

Justin indicates to his mom that he would like to speak to me. My aunt takes his hand and he hunches over the board, spelling out slowly but deliberately, "Say I'm not stupid." He lifts his head and looks at me with tears pooling in his big, blue eyes. I am fighting a lump in my throat as I exclaim, "Of course you're not stupid! I've known that your whole life." He returns to the letter board. "Say I'm nice."

"You are one of the nicest people I've ever met," I tell him, and I mean it. Justin climbs into my lap and wraps his arms around my neck, giving me a long, tight hug. Although affectionate, Justin's hugs are usually brief, one-armed gestures used to say thank you or goodbye. I know without looking into my aunt's damp eyes that this hug means something big, for me and for Justin.

Since Justin first reported being called stupid to my aunt, she has spoken to his class about Autism and even gave a demonstration with the letter board to show how Justin communicates with her. "He can talk?" several students asked in surprise. "He can spell?"

Kids will be kids, and some of Justin's classmates who see him as an easy mark continue to pick on him, but others have stepped up and offered friendship and support to my cousin. As I told Justin, people make fun of what they don't understand. Once you get to know Justin, he is impossible not to love.

Next weekend is Justin's first birthday party with children from his new school. I know he'll be busy with his friends and his gifts, but I selfishly want him to spend some of the time just talking to me. I think about all the years of dialogue that must be boiling inside of Justin, ready to burst, and how he must say things one letter at a time. He'll get quicker, I know. Soon I'll be the one struggling to keep up with him, trying to follow his hands as they fly across the letters on his board.

I feel as though I am getting to know someone I've just met, yet talking to someone I've known my whole life. Hearing Justin is teaching me to appreciate the things that matter about a person: their kindness, their eagerness to learn, and their compassion.

Justin would like me to tell you a few important things. First, he is not stupid. Second, he is nice. And third, if you are interested in learning more about the Rapid Prompting™ Method that gave Justin his voice, please visit http://www.halo-soma.org/learning_faqs.php.

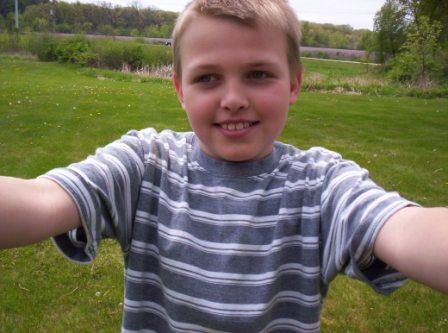

My brilliant cousin Justin.

This essay will be featured in the winter 2008 Hear Our Voices magazine, which is produced by "I Care 4 Autism." To learn more, visit http://www.icare4autism.org/.