Two sticks cup the ball on either side. Twelve women are frozen in position on the lacrosse field at Stevenson University in Baltimore, Md. The whistle blows. Pop! The ball comes free and play is on.

Each pass is clean, extended with precision ease. Stevenson's Olivia Baker senses a defender approaching on her right. She swerves and looks across the field to a teammate. She spots middie Laura Grammer wide open. But what Grammer doesn't see is an Elizabethtown opponent creeping quickly up her blindside.

As Grammer extends her stick to receive the pass, Elizabethtown's No. 22, Katie Scheurich, reaches her left arm up and hits Grammer in the neck with her bicep. Scheurich's body weight falls into Grammer's side as she collapses on Bermuda Grass Field.

After slowly rolling onto her side, Grammer stands up gingerly. Taking a minute to collect herself, she sets one foot back, bends forward and holds her stick up. The whistle blows and play is on. She sprints full tilt downfield.

Grammer went on to play after experiencing a hit players, coaches and referees have seen countless times before. And when a high school sports-related surveillance study over the 2009-10 school year revealed head/face injuries/concussions as the most common injury in girls lacrosse competition, it raised questions about safety but also the differences in how men and women play the game.

When head injuries do occur in the women's' game, it is typically inadvertent stick -- or ball-to-head contact, more frequent in games than practices, U.S. Lacrosse said in a presentation on Nov. 16, 2010 to the New York State Public High School Athletic Association, "Men's Lacrosse Helmets in Girl's Lacrosse: Concerns About Player Safety and Game Integrity."

While concussions making up a fourth of injuries suffered may be high, the percentage has actually decreased significantly from '08-09, when 37 percent of injuries were above the neck. Still, the NCAA looked to lower the number even further and approved new rules to go into effect for the 2011-12 season. The rules strengthen the power of the penalty card, corresponding a harsher penalty with yellow and red cards to dissuade girls from playing as aggressively.

U.S. Lacrosse, which monitors rules and regulations at the youth, high school and post-collegiate level, wanted to see that become a reality as well. The governing body instituted a similar rule change prior to the 2010-11 season and will know how effective it was at the end of the year.

Other sports have turned to headgear for the answer to the head injury problem, and some insist helmets are the answer here.

Dr. Kevin Crutchfield, director of the Comprehensive Sports Concussion Program at the Sandra and Malcolm Berman Brain & Spine Institute of LifeBridge Health in Baltimore, Md., believes women need helmets to protect them from flying balls hitting them in the head, but also said enforcing the rules more strictly would reduce injuries in women's and men's lacrosse.

Like the NFL's action in 2009, U.S. Lacrosse needs "to protect the players more," Dr. Crutchfield said. "Injuries went down exponentially last year when [the NFL] started fining people and enforcing the right rule."

Grammer, who played for Parkville High School in Baltimore, Md., before college, would like to wear a helmet because she sees a lot of contact during games and practices, but she worries introducing helmets will make the game more aggressive.

"It's gotten a lot more dangerous since I've started playing," Grammer, 20, said.

Eye wear was instituted in 2004 after injuries to the eye became common and considered catastrophic. "They've added more contact and stuff like that," Grammer said. "Before, we never wore goggles. We just had a mouth guard, but then people started getting hit in the eye. Well, now we're getting hit in the head."

Ricky Fried, Georgetown University's women's lacrosse coach, understands the concern behind wanting to require helmets, but also has seen no concrete reason for the change.

"I've been coaching for 18 years and I haven't seen any serious head injuries due to a check or a shot," Fried said. "The injuries we've seen are ones that really won't be prevented by a helmet. People falling down, hitting their head on the ground that leads to a concussion will also lead to a concussion if you have a helmet. So while there is some risk in the 18 years I've been doing this -- and I know it's changed a lot medically -- I can probably count on one hand the amount of concussions that have occurred and I would say the majority of those are from people falling, not from getting checked or getting hit with the ball."

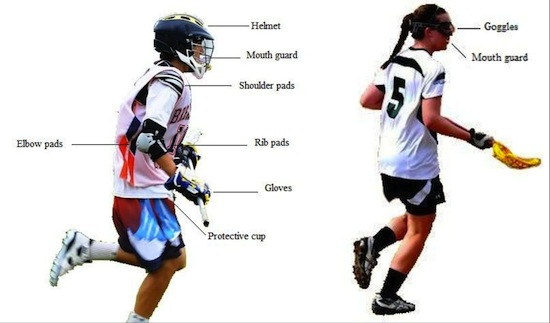

Helmets are required in men's lacrosse because the game is more physical than the women's game. Really, they are two completely different games. There are 10 players on the field during a men's game; 12 for a women's game. Women play halves; men play quarters.

But the most important distinction is men are allowed to body check, which means they can use their bodies to defend and potentially steal the ball out of opponents' sticks. They wear padding and helmets for protection. For women, body checking is not allowed. Stick checking is the preferred defensive maneuver.

Because the games are played so differently, the question of whether to put helmets on females in lacrosse becomes not just a struggle over headgear. Rather, it reflects a deeper debate about questions of aggression and equity in women's and men's sports.

Victoria Michel, a former player at Centennial High in Ellicott City, Md., headed to Shepherd University in the fall, said girls who play lacrosse know and understand the game. She argues better enforcement of the rules by officials during games and coaches in practice would result in a lower incidence of injury.

"Girls' lacrosse should never have to need helmets," Michel said. "Because it's not how you play. You don't play by hitting somebody; you play by using your stick skills and all your other capabilities to get your ball across the field."

Though soft headgear is an option for women in the rule book now, there is not a standard. This summer, U.S. Lacrosse decided, with help from the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE), to design a soft standard for female-specific helmets since using the men's design for women was speculated might actually increase injury in women, just one of the many struggles in understanding the differences in the two games.

Women's lacrosse is a derivation of the men's game Native Americans played first. In 1890, headmistress Louisa Lumsden traveled to Montreal, saw the game and introduced it at her school, St. Leonard's in Scotland. A former student, Rosabelle Sinclair, brought the game back to America in 1926 when she established the first women's lacrosse team at Bryn Mawr School in Baltimore, Md., which even in the last five years ranked consistently in the top 10 in the IAAM.

The men's and women's games were played by the same rules until the 1930s, when women began to separate themselves, playing a less physical game and more of a finesse game. Proponents of education over the tangible solution of helmets feel enforcing these rules more stringently will reduce injuries.

"There are at least 10 areas you should be focusing on that each reduce concussions marginally," Chris Nowinski, president and founder of the Sports Legacy Institute, said. "It has to do with education, it has to do with technology, it has to do with rules, it has to do with referees, it has to do with equipment. All of those things should be addressed in the context of brain trauma."

Automatic carding for violent checks in women's lacrosse has been in the rule books for at least 22 years, but rules changing the penalty for carding went into effect last season for all levels of play except collegiate.

According to Melissa Coyne, women's game director for U.S. Lacrosse, a second yellow card in a game means a player sits out the rest of that game and the next game. Get a red card, add one more game. With a short season of less than 20 games, players were upset at being forced to sit out even one.

But in June, the NCAA approved a similar carding rule to be implemented in the 2011-12 season. According to Pat Dillon, secretary/rules editor for NCAA women's lacrosse, if a player receives a card she will sit out for two minutes and her team will play man down, restricted below the restraining line. The NCAA's hope, according to Dillon, is the inability to defend or score with the standard amount of players will "strengthen the penalty thus discouraging dangerous play which in turn would hopefully make the game safer."

Coyne also believes in making the game safer, the rules need to be consistent. The board of directors for U.S. Lacrosse will vote in September to institute standardized rules at the youth level of play. Currently, the provisions Coyne and her team are proposing are considered "acceptable modifications" to the rules, which means a game played in one state could have one set of rules, while another state could have another set of rules. This leads to unsafe practices, confusion for parents and athletes, and disconnect from a developmental standpoint.

"We're just trying to be consistent with the rules across the board," Coyne said. "And the more consistent we are, the safer our game is and the less discussion there will be about helmets."

Justine Allen, who missed 12 games of her freshman season at the University of Vermont due to a full body hit with a teammate in a preseason practice, has seen the effects head injuries can cause, but still is unsure whether helmets are the way to go.

"You shouldn't need a helmet playing women's lacrosse because it should be skilled and controlled enough," said Allen. "Women's lacrosse is less contact. It's more like playing with your feet, kind of more like basketball than hockey, which is what men's lacrosse is like. It's more using your body, not your stick."

Nowinski said when helmets were added to sports they've "made the game more dangerous for concussions."

"Every sport that's added a helmet has changed the way they play. I don't believe that administrations/referees have shown the will to police the sport hard enough that the addition of helmets would make it safer overall."