About two and a half years ago, a pharmaceutical company developed a miracle cure with the potential to eradicate a terrible disease from our planet. It was an American pharmaceutical company, so this miracle cure can be seen as a triumph for our using a market system to encourage the development of cures. With this cure we could potentially wipe out a significant disease for the first time since small pox was eradicated almost 40 years ago.

And yet two and a half years later, this disease has remained almost completely untouched.

Why no miracle? Does the cure take a long time? No: From the time the treatment is started, it takes only about 12 weeks. Is it difficult to administer? No: 1-2 pills a day, taken at home, for twelve weeks. Are the pills hard to get, or expensive to make? Well that depends on exactly what you mean.

First, let's set the stage.

The disease is hepatitis C: a virus that slowly destroys a person's liver, usually over the course of several decades. It's not easy to catch and doesn't have many symptoms until the late stages. Prior to 1992 it was spread mostly through blood transfusions, when no one knew how to screen for it. It can also be spread by contaminated needles. The most common ways to contract hepatitis C today are by IV drug use, and being a health care worker who is accidentally stuck by a needle. Because hepatitis C is so hard to transmit, the number of people who contract it each year in the developed world has declined significantly in the last 25 years.

Still, an estimated 3-5 million people have hepatitis C in the United States, with 7-9 million more in Europe and perhaps another 185 million worldwide. If left untreated, many of these people will eventually suffer from liver failure or liver cancer, and die if they don't receive a liver transplant.

Hepatitis C has been treatable for many years but previous treatments were far from adequate. They required expensive injections that had many side effects and often didn't work. Then, in late 2013 Gilead Sciences released a revolutionary new drug called Sovaldi which was more effective and far easier to use than prior hepatitis C treatments, and then in 2014, an even better treatment called Harvoni.

These two wonder drugs can potentially cure hepatitis C over 90 percent of the time in just 12 weeks. That's even more impressive than it seems: since hepatitis C is so difficult to transmit, eliminating most of the carriers with oral medication could lower the transmission rate to the point where the remainder of the disease would likely disappear on its own.

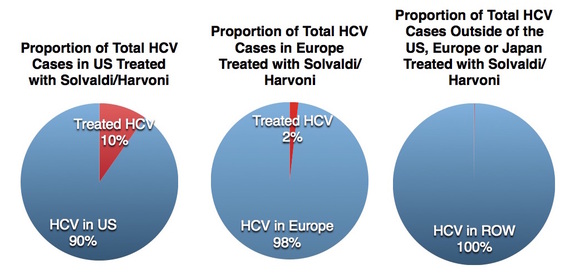

But that hasn't happened yet. In fact, surprisingly few cases of hepatitis C have been cured by these wonder drugs. According to Gilead Science's own records only 378 thousand people in the US have been treated with either Sovaldi or Harvoni, another 145 thousand people in Europe, and 250 thousand people in the entire rest of the world combined (slides 27-28). That means that, after two years, only about 10 percent of people with hepatitis C in the US, 2 percent of Europeans and a small fraction of a percent of those in the rest of the world who have this disease gotten this miracle cure.

So we return to our first question: why?

The main reason appears to be that these drugs are really incredibly expensive, so almost no one can afford them. Solvaldi cost $1,000 a pill when it was released in the US and Harvoni cost $1,125 a pill. These drugs are somewhat less expensive in other countries, but they cost at least $50,000 to $100,000 for a full course in any developed country. In fact, Sovaldi was the single most costly drug for Medicare's prescription drug plan in 2014, costing Medicare over $3 billion to treat about 33 thousand people.

That's too much money for most people -- and most insurance plans -- to spend on curing a disease that, while often lethal, usually takes many years to kill a person.

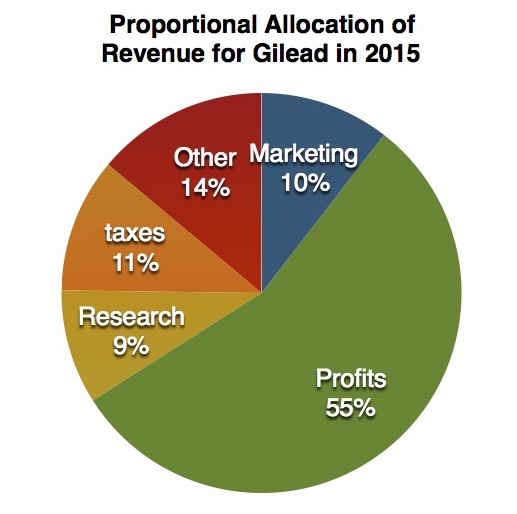

Yet since Gilead released these two medications, they've tripled their annual revenue, and last year alone, they had a 55 percentafter tax profit margin. That's one of the highest profit margins for any corporation in any industry. Gilled made more in profit last year than Bank of America, Exxon Mobil, General Motors, Walmart, Microsoft or any of the other pharmaceutical companies.

This shows two things. First, their business model -- pricing a wonder drug out of the reach of nearly everyone who needs it -- works, provided you care only about money. But second, it shows that clearly the drug could be sold profitably for much less. So the question is: why not reduce the price and and make up the profit in volume of sales?

If Gilead did that, they could possibly eradicate hepatitis C. That's good for the world, but terrible for their future finances. By treating only a few patients each year, the infection pool stays large enough to maintain Gilead's revenue for years to come.

This example shows that our current method of funding medical research has a downside. We allow pharmaceutical companies to name their own prices for drugs with the promise they'll use that money to fund research that might develop miracle cures. This system can provide a great incentive for finding new cures. But then it can also provide an equally strong incentive to avoid eliminating a disease, at least in most people. Why would any company want to wipe out a disease and so kill its own Golden Goose?

Clearly the Gilead example shows that the purely market-driven system can work. The question is: does it work the way we want it to?