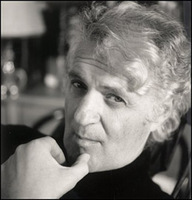

Herb Gardner, one of the greatest but most under-appreciated playwrights in 20th century America, died 10 years ago today.

I admit to being, like thousands of other baby-boomers, part of a cult - lovers of Gardner's remarkable play, "A Thousand Clowns," which debuted on Broadway in 1962 and was turned into a film three years later.

Gardner's biggest commercial success was "I'm Not Rappaport," a 1985 play which ran on Broadway for two years, captured the Tony for Best Play and Best Actor (for Judd Hirsch), then became a popular film, starring Ossie Davis and Walter Matthau. "The Goodbye People" (1968), "Thieves" (1974), and "Conversations With My Father" (1992, which was nominated for a Pulitzer) also began as plays and became films that received mixed reviews but deserve a second, and third, look. Even "Who Is Harry Kellerman And Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me?" a Gardner short-story turned into a 1987 film with Dustin Hoffman that was almost universally panned (with the exception of Barbara Harris, who received an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress), has many redeeming moments.

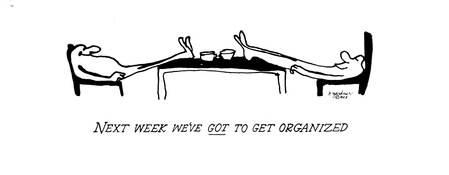

Gardner's autobiographical novel, A Piece of the Action (1958) is not only an entertaining read but offers insight into the author's first career, as a cartoonist whose greatest creation, The Nebbish, which he began drawing while a student at Antioch College, became a popular culture sensation. The comic strip was syndicated in over 60 newspapers from 1959-61, while the character became a ubiquitous presence adorning cocktail napkins, drinking glasses, greeting cards, and posters.

But Gardner's greatest creation was "A Thousand Clowns." It may be the best film of the century, but it is virtually forgotten except among Gardner cultists, who have memorized its unforgettable lines and revel in its bold irreverence.

Jason Robards starred in the play and the movie as Murray Burns, forced to choose between returning to a job he had quit five months earlier (as a writer on a mindless childrens TV show, "Chuckles the Chipmunk") or losing custody of his precocious orphaned 12-year-old nephew, played on stage and in the film by the remarkable Barry Gordon. (I had the good fortune to meet Gordon - a well-respected character actor and former president of the Screen Actors Guild - when he was running for Congress in 1998. He called me out of the blue to ask for my support. I nearly fell out of my chair when I realized this was the same Barry Gordon who had starred in "A Thousand Clowns." Despite the house party that I hosted for Gordon's campaign, he lost that election, but he has continued to be an important progressive voice, cable TV host, and occasional newspaper columnist in the Pasadena area).

After Gordon's character Nick writes a school essay on the benefits of unemployment insurance, his school contacts the Child Welfare Board to look into his unusual living circumstances. The agency sends two investigators - Sandra Markowitz and Albert Amundson, wonderfully played by Barbara Harris and William Daniels. They threaten to remove Nick from Murray's over-crowed apartment unless he takes a job to show he's a responsible guardian.

Murray resists returning to the "Chuckles" show but can't find another job that he doesn't think is equally mind-numbing. He'd rather spend his days roaming around New York, such as going to the peer to wave good-bye to complete strangers about to leave on a cruise ship. Murray's brother Arnold, played by Martin Balsam (who won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar), visits regularly to convince Murray to go straight in order to hold onto Nick. Murray can't stand the thought of taking a stable job, but eventually Nick, Arnold and Ms. Markowitz (who becomes Murray's girlfriend after ditching the straight-arrow Amundson) persuade him to return to the Chuckles show for the sake of the nephew he obviously loves.

After a brilliant scene between Murray, Nick and the pathetic Chuckles (played by Gene Saks), Murray resigns himself to going back to his old job. In the film's last scene, we watch Murray join the crowds of New Yorkers, briefcases in hand, heading off to work.

Some might view that ending as a defeat for the world's free spirits. But I was taken by Murray's uncompromising love for Nick and his unabashed love of life that nothing - not even Chuckles the Chipmunk - could destroy.

I first read the play in 10th grade, thanks to a daring and caring English teacher who guessed (correctly) that I would identify with the character of Nick. The play changed my life and outlook forever. Like MAD magazine, "Catcher in the Rye," and Jean Shepherd's subversive radio program, "A Thousand Clowns" reflected the burgeoning, somewhat under-the-surface critique of American consumerism and middle-class comformity that first expressed itself as Beat culture and later flowered in the Hippie explosion. I was neither a Beat nor a Hippie, but the film's iconoclasm certainly played a role in provoking many young Americans (including me) to look twice at aspects of American life that they might otherwise have taken for granted. It helped sow the seeds of 1960s radicalism.

It still amazes me that "A Thousand Clowns" - which was nominated for the Best Play Tony and Oscars for Best Film, Best Music, and Best Writer along with Balsam's Best Supporting Actor trophy - is so little-known today, as least as a cultural marker reflecting the transition from the comformist 50s to the rebellious 60s.

"A Thousand Clowns" not only reflected the cultural tensions of the times, but also included some of the greatest lines in the history of American cinema, many of which make sense only to those who have imbibed the play or the film. These include:

- Murray (to Nick): "Better go to your room"; Nick: "This is a one-room apartment"; Murray: "OK, then go to your alcove."

- Murray: "You can never have too many eagles."

- Nick: "You want to be your own boss but the trouble with that is you don't pay yourself anything."

- Murray: "Elaine [Nick's mother, who abandoned him] communicates with me almost entirely by rumor."

- Murray: "You might call Nick a bastard... or a little bastard, depending on how whimsical you feel at the time."

- Murray: [leaning out from his apartment window]: "This is your neighbor speaking. I'm sure I speak for all of us when I say that something must be done about your garbage cans in the alley here. It is definitely second-rate garbage. Now, by next week I want to see a better class of garbage, more empty champagne bottles and caviar cans! I'm sure you're all behind me on this. So let's snap it up and get on the ball! "

- Arnold (after setting up job interviews for his reluctant bother]: "Murray, you've got a rotten reputation. Even these guys weren't easy to grab. Why do you have to build your own personal blacklist? Why can't you just get blacklisted as a Communist like everybody else?"

- Albert Amundsen: "You are not a person, Mr. Burns. You are an experience!"

- Murray: "I just want him [Nick] to stay with me until I can be sure he won't turn into Norman Nothing. I want to be sure he'll know when he's chickening out on himself. I want him to get to know exactly the special thing he is or else he won't notice it when it starts to go. I want him to stay awake and know who the phonies are. I want him to know how to holler and put up an argument. I want a little guts to show before I can let him go. I want to be sure he sees all the wild possibilities. I want him to know it's worth all the trouble just to give the world a little goosing when you get the chance. And I want him to know the subtle, sneaky, important reason why he was born a human being and not a chair."

- Murray: "I gotta know what day it is. I gotta know what's the name of the game and what the rules are without anyone else telling me. You gotta own your own days and name 'em, each one of 'em, every one of 'em, or else the years go right by and none of them belong to you. And that ain't just for weekends, kiddo."

- Murray: "Irving R. Feldman's birthday is my own personal national holiday. I did not open it up for the public. He is proprietor of perhaps the most distinguished kosher delicatessen in our neighborhood, and, as such, I hold the day of his birth in reverence. "

In "A Thousand Clowns" and his other works, Gardner (1934-2003) revealed comic brilliance, insight, irreverance, and a deep humanism. His plays and films dealt with serious subjects - anti-semitism, racism, aging, family loyalty, tensions between children and parents, marriage, crime, and the blandness of most TV shows, among them - but you never felt you were being lectured at.

Gardner once recalled that as a youngster growing up in New York, he hung out in a local deli where aging Jewish radicals spent hours discussing "either Leon Trotsky or the egg salad."

Those experiences show up in "I'm Not Rappaport." Nat, an 81-year-old Jewish lefty, and Midge, an nearly blind apartment-building maintenance man, meet each other on a Central Park bench, where they fend with junkies, thieves, Nat's daughter (who wants to send him to a nursing home), and the co-op board that wants to fire Midge. Nat uses his lifetime of activism and bravado to fight the powers that be, an idealist to the end.

Reflecting on his Nat character, Gardner observed: "In my history there were these extraordinary guys, men and women, all immigrants, passionate people, who believed a great, humane kind of America existed--and when it didn't, they decided to make up the difference."

I can't think of a better way to describe a radical.

Peter Dreier teaches Politics and chairs the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His latest book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame.