Colonial School District straddles the boundary where suburban Wilmington gives way to Delaware's rural eastern shore. Its one high school, William Penn, serves a racially diverse population, about 40 percent of whom come from low-income families. Penn is a model for getting kids ready for life after graduation. Ninth-graders who enter its doors are asked to choose among 19 "degree programs" -- essentially, career tracks ranging from construction to engineering -- that will be their focus for the next four years. But there's one choice they don't have to make: Whether their "degree" will prepare them for college or the workforce. At William Penn, all graduates will be ready for both.

During a recent visit there I spoke with a senior in the school's culinary arts program who exemplifies the Penn way. In addition to his studies in the busy kitchen, which doubles as a student-run catering business, he has six AP courses under his belt along with his industry certification. Elsewhere in the building I saw physics being taught in a wood shop, while in another more traditional classroom, 11th-graders explored issues of race and equality in Kurt Vonnegut's dystopian story "Harrison Bergeron."

Our studies at the Center for Public Education show that William Penn High School's approach can be a winning formula for all students. For the last two years, our senior policy analyst, Jim Hull, has been examining longitudinal data on the high school graduating class of 2004 in order to identify factors related to later economic and social outcomes for individuals who do not go to college. The findings have been published in a series of reports we call "The Path Least Taken" which reflects our initial discovery that non-college goers represent a small proportion of high school graduates. At age 26, only about one in ten had never enrolled in a college.

Like many other studies, we found that going to college is generally better than not going at all. Enrollment in a two- or four-year institution increases the chances that individuals will be employed full-time, earn higher wages, as well as vote and volunteer in their communities. As an overall group, non-college goers faced the dimmest prospects. But not all of them.

By drilling into the data, Hull found that some non-college goers fared well in comparison. These individuals in high school had taken high-level math and science, earned a C+ grade point average, and completed an "occupational concentration" of at least three courses in a specific labor market area. Throw in a professional license or certificate and these 26-year-olds performed better economically than the overall group of their peers who had enrolled in college. We labeled this combination of attributes "high credentials."

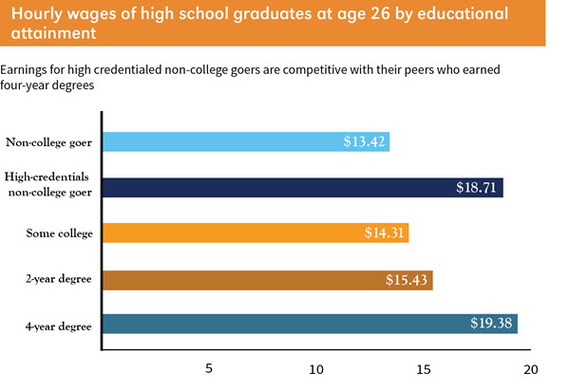

On June 1, we released the third and final installment of the series in which we were able to identify and compare the outcomes of non-college goers against those who had some college and those who actually earned a degree. Again, the overall group of non-college goers was outperformed in virtually every category. However, the "high-credentialed" non-college goers had better outcomes than those with some college but no degree, as well as two-year degree holders. Moreover, they were competitive with four-year college completers on several indicators, including hourly wages and full-time employment.

"High credentials" also boosted prospects for high school grads who went to college, but didn't earn a degree. Compared to their peers who also left college early but lacked high-level courses and focused career training in high school, those with high credentials saw much better chances for higher wages and good jobs.

The implications of these findings for education policy couldn't be clearer. Schools need to assure that all high school students have the benefit of high-level academics and get the support they may need to succeed in these courses. Students also need access to modernized career and technical education (CTE), including programs that lead to professional certification.

Keep in mind, this is not your father's vocational ed. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) put it well during a mid-May Congressional hearing on the Perkins Vocational and Technical Act, which is currently due for reauthorization. Sen. Kaine acknowledged that the history of voc ed was too often an inferior alternate for students who weren't considered "college material." In his testimony he stated: "[T]here is a history of tracking students into vocational education, and we must ensure that federal CTE investments replace tracking with choice. Students and their families should have the opportunities to choose high quality CTE pathways that will prepare students for postsecondary education AND the workforce, not postsecondary education or the workforce."

The William Penn senior I met could just as easily be headed to a college campus as to a restaurant kitchen after receiving his diploma. He told us that, in fact, he has enlisted in the military where he plans to use his culinary skills. College, he said, is still in his long-range plan. Fortunately, his high school made sure he has the knowledge and skills to keep all his options open. All of our youth deserve the same.