Should Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan 1839-42 be read as an account of the first Afghan war in its own right, or as a cautionary tale in the context of Afghanistan today? The question is pointless -- the answer is "yes" to both options -- because all history is written with at least implicit reference to its author's own times. And William Dalrymple is helpfully willing to be quite explicit on this point: He acknowledged to Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian that there was "an element of calculation" in the book's timing; and near the end of the book itself he writes that, "despite all the billions of dollars handed out [since 2001], the training of an entire army of Afghan troops and the infinitely superior weaponry of the occupiers, the Afghan resistance succeeded again in first surrounding then propelling the hated Kafirs into a humiliating exit."

It's hard to be much more explicit than that but, perhaps aware that Americans sometimes need things to be spelled out very explicitly indeed, just three days before the book's April 16 U.S. publication date, Dalrymple published a New York Times op-ed in which he quoted a recent Taliban press release that claimed: "Everyone knows how Karzai was brought to Kabul and how he was seated on the defenseless throne of Shah Shuja. So it is not astonishing that the American soldiers are making fun of him. ... It is the philosophy of invaders that they scorn their stooge at the end." But in order to appreciate the effectiveness of that nugget of Taliban propaganda, you need to know who Shah Shuja was. "We may have forgotten the details of the colonial history that did so much to mold Afghans' hatred of foreign rule," commented Dalrymple, "but the Afghans have not."

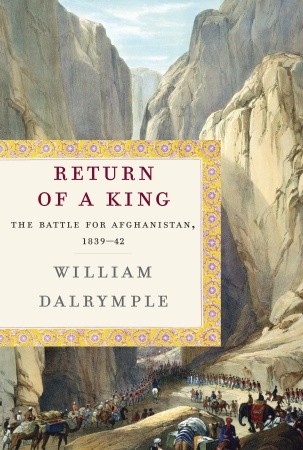

In Return of a King, Dalrymple has done again what he did magnificently for two other telling episodes of British imperial history in White Mughals (2002) and The Last Mughal (2006). He told Jeffries that he sees the three books "very much as the East India Company trilogy," and that is a very correct and useful way to see them. Until further notice, the trilogy must be read and assessed as the crowning achievement of Dalrymple's career.

Any summary a reviewer could offer would be the merest potted version of what took the author years of research to stitch together, so I prefer to urge you to read the book itself. A professor who assigned The Last Mughal in a university class I attended a couple of years ago described it as "a ripping good yarn," which is a way of saying that Dalrymple has a narrative gift. The aesthetic enjoyment we find in such books is a good thing in itself, and of course it's important at the same time to keep in mind both the horrific reality of the events they depict and their enduring relevance: Mark Twain's hoary but true adage that history doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme.

Another professor recently told me he's already getting blank stares from students when he refers to the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center. Our choice as a species is either to yield to the understandable ignorance of each new generation, and our proclivity to indulge and enforce forgetfulness of our embarrassments, or to resist these. This is why the study of history is important. Dalrymple makes it enjoyable by writing well and engagingly, but it's up to us as readers to meet him halfway. I would add that it's important to write and read at book length, because narration is a truer facsimile of historical reality than bullet points or video or tweets.

The history of human folly rhymes back through Saigon in 1975 and Dien Bien Phu in 1954, through Delhi in 1857 and Kabul in 1842, Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, et cetera, all the way back to the fall of Rome. Indeed there's something Gibbonian about Dalrymple's three history books, much less in the tone -- Dalrymple is not orotund but friendly and patient -- than in the fondness for footnotes and, more basically, in the cautionary intention.

Americans need to refer first not to Rome, though, but to Vietnam, which our society never dealt with honestly before plunging into similar tragic follies in Afghanistan and Iraq. Indeed reading Return of a King, with its author's insistence on documenting the myopia of many of the British political and military leaders of the time, kept bringing to mind The Experts: 100 Years of Blunder in Indo-China (1975) by Clyde Edwin Pettit (alternate subtitle: The Book That Proves There Are None), which is nothing but 439 pages of mostly myopic quotations, artfully selected and arranged to constitute a chilling and implicitly incisive narrative. The fact that Pettit's masterpiece is largely forgotten is very much to the point, and so is the fact that it shouldn't be.

(Speaking of Saigon, and the South Vietnamese who were abandoned as the helicopters lifted off the roof of the U.S. Embassy almost exactly 38 years ago -- on April 30, 1975 -- just as I was finishing this review I saw this headline featured prominently on the New York Times website: "Afghan Interpreters for the U.S. Are Left Stranded and at Risk.")

ETHAN CASEY is the author of Alive and Well in Pakistan: A Human Journey in a Dangerous Time (2004), called "intelligent and compelling" by Mohsin Hamid and "wonderful" by Edwidge Danticat. He is also the author of Bearing the Bruise: A Life Graced by Haiti (2012) . His next book, Home Free: An American Road Trip, will be published in fall 2013 and is available for pre-purchase. Web: www.ethancasey.com or www.facebook.com/ethancasey.author. Join his email list here.