Today marks the 40th anniversary of the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge. It is an event that made hardly a blip on the radar of international news back then, and its remembrance four decades on is likely to make even less of one.

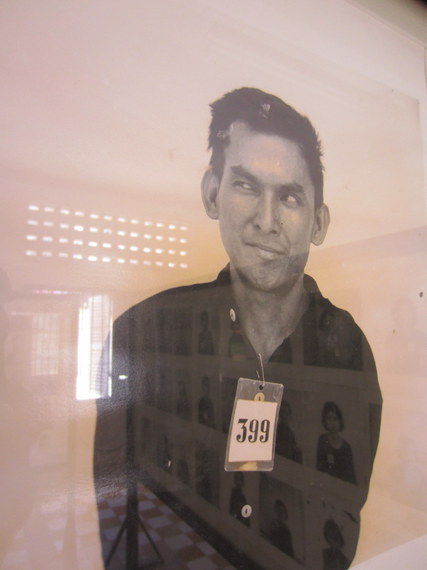

Kurt Vonnegut wrote that there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. One certainly gets that feeling when reading documents detailing Pol Pot's social experiment or wandering the mass graves at Choeung Ek that were that experiment's result. The evacuation of cities, the slaughter of intellectuals, the reset of time to Year Zero, the work camps and limited rations and pledges of allegiance to Angka; it was all a kind of madness unworthy of the small dignity explanation might bring.

What, then, can we learn? How might we honor the senselessly dead? It seems to me that as someone not from Cambodia, and especially as an American, the biggest takeaway from the tragedy of the Khmer Rouge regime is an understanding of the larger geopolitical context from which those events cannot be removed. Nothing about the political trajectory of Cambodia in the 1970s can begin to be understood without accounting for the American war in Vietnam. Kampuchea, as it was then known, was a stable, peaceful, and happy country whose leader, Norodom Sihanouk, strove to keep it from becoming embroiled in the war next door.

When a U.S.-sponsored coup in 1970 ousted Sihanouk while he was away on a diplomatic trip, the leader relocated to Peking and formed the National United Front of Kampuchea. In order to overthrow General Lon Nol and the puppet government that had just unseated him, Sihanouk used the same widespread popularity that had kept radicals at bay to swell the ranks of the Khmer Rouge. Peasants that had little understanding of communism joined Pol Pot's revolution as an act of loyalty to the king, and after a visit from Sihanouk in the field the rag-tag group of fighters in black pajamas and tire-tread sandals grew from 6,000 to 50,000.

It was the installation of Lon Nol, combined with the nearly 3 millions tons of ordnance dropped covertly (to everyone except those on the ground, of course) on Cambodia from 1965-73 that set the stage for April 17, 1975. The responsibility for the actions that followed remain with the actors, of course, but the state of affairs that made them possible had everything to do with much larger political trends, and American foreign policy in particular.

The most recent American war in Iraq is perhaps too often compared with Vietnam, and my point here is not to conflate them yet again. Still, some comparisons are instructive. Similar to the Khmer Rouge, the creation of ISIS would never have happened without our misguided and immoral military occupation of Iraq. One overarching theme of these largely disparate conflicts is the law of unintended consequences. It is almost impossible to predict what the fallout will be when any military intervention begins. What is almost certain is that death, destruction, and chaos will reign in ways and to degrees that we could never have predicted.

All of this feels especially pertinent in the atmosphere that surrounds the current nuclear deal with Iran. Even as our world continues to make sense of the aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, our military-industrial complex seems to have the attention span of an 8-year-old on an iPad. A certain junior senator from Arkansas with a very bad haircut has made a habit of talking about war with Iran as if it is a matter of when, not if. The danger inherent in treating such grave decisions as though they are foregone conclusions should be obvious. The tactics of such hawks has not changed much in the last 50 years: stir up fear among the populace by suggesting that inaction or attempts at diplomatic negotiations will be the kiss of death, make it clear that your enemy is cannot be reasoned with, much less trusted, and convince otherwise peaceful citizens that the other side is so completely devoid of any kind of recognizable morality that a first strike is just and justified.

What I'd like to suggest as an appropriate way to remember the millions of Cambodian lives that were forever altered four decades ago is an increased commitment to peace at all costs. Said so plainly, such a sentiment is trite and impotent, little more than lip service to a grand idea. But since it seems clear that some of our elected officials are eager to lead us down another path to war and long list of unintended consequences therein, we have some work to do. We are a nation of mostly decent, hospitable, and generous people that could never condone the slaughter of innocents and the unsettling of entire societies. As a citizenry we must be reminded that our government is what we make it and nothing more. We still have, if we choose to exercise it, the power to build a future free of mass graves and minefields and genocide memorials. Those of us that oppose such atrocities are many, we must simply summon the will and imagination to question the obscene logic of the perpetual war economy.

I'm reminded of the George Saunders piece written as a manifesto for the imagined group People Reluctant to Kill for an Abstraction. He describes this group's members as people that have "gone about our work quietly, resisting the urge to generalize, valuing the individual over the group, the actual over the conceptual, the inherent sweetness of the present moment over the theoretically peaceful future to be obtained via murder." It's too easy to distance ourselves from the kinds of transgressions Saunders craftily alludes to, but the sobering truth is that if we're going to prevent more disastrous missteps our policy makers need these words in 2015 as much as the Khmer Rouge did so long ago.