If you're admitted to a hospital, the last thing you should need to worry about is developing an infection linked to your care. Sadly, it occurs too often.

And consider startling numbers about the consequences: About 1 of every 20 patients gets an infection while hospitalized and up to 98,000 Americans die from these each year. That makes infections the most common complication in hospital care and one of the nation's top 10 causes of death. In California, an estimated 200,000 patients develop hospital infections each year, resulting in 12,000 deaths.

The problem is likely even greater than official figures suggest because those numbers fail to account for millions of patients treated in outpatient surgery centers, community clinics, nursing homes and other care facilities.

These infections can be devastating to patients and families. They're bad, too, for the health care system, adding as much as $45 billion a year to U.S. medical bills. That's troubling when you consider that the U.S. already spends far more per capita on health care than other industrialized countries -- without the added financial burden of this home-grown problem.

There is good news here: Epidemiologists widely agree that hospital-acquired infections can be prevented. And many hospitals are redoubling efforts to eradicate this invisible menace. Doctors, nurses and other health care workers are stepping up hand-washing campaigns, taking extra care to sterilize medical equipment and removing unnecessary catheter lines that can become bacterial breeding grounds.

Hospitals have reason to act: Uncle Sam is paying close attention. Under the new health care law, hospitals with infection rates exceeding national averages stand to lose 1 percent of their Medicare funding, starting in 2015. That may not seem like much, but it's a big stick when you consider the federal government spent $563 billion last year on 49 million Medicare recipients. Medicare spending is expected to reach $970 billion by 2021.

The government is especially scrutinizing infections linked to medical devices such as catheters or ventilators and those related to surgical sites, where bacteria can infiltrate the blood stream, the urinary tract, the lungs or other parts of the body.

Physicians, Wash Thy Hands

While efforts to guard against these infections are crucial, too many hospitals still do too little to tackle this urgent public health threat. And doctors, I'm sorry to say, are some of the biggest culprits. Although major evidence exists that hand hygiene is the best way to reduce hospital-acquired infections, many doctors still don't soap up before examining patients.

A report in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that hand hygiene rates among doctors and other health care workers averaged "40 percent to 60 percent on a good day."A separate study at a large university hospital found that doctors washed their hands just 57 percent of the time when seeing patients.

And it's not just an American problem. A study of hand hygiene in an English teaching hospital found that doctors washed their hands just 47 percent of the time when seeing patients. Nurses, at 75 percent, were better but far from perfect. Visitors also came up short: Only 57 percent of them washed their hands.

Shouldn't doctors and nurses know better, especially given the well-known connection between hand washing and infection control -- a link first made by a Hungarian doctor 165 years ago?

Back in 1847, physician Ignaz Semmelweis worked in a Viennese maternity hospital with two clinics, one staffed by doctors and the other by midwives. He noted that the mortality rate in the doctors' clinic was substantially higher than in the one run by midwives. He observed that doctors and their students went directly from autopsy rooms to the delivery suite, carrying a foul odor on their hands even after washing with soap and water. The doctors, he theorized, infected mothers and newborns with cadaver germs. He got the doctors and interns to wash their hands with chlorinated lime solutions before examining patients in the maternity ward. The mortality rate plummeted. Many now regard Semmelweis as the father of hospital epidemiology, and they're carrying on his legacy.

An Institutional Campaign

The leadership of my own hospital, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, has taken an aggressive approach to hand hygiene, even calling out doctors who don't comply with stringent new rules. Our hand hygiene campaign began half a dozen years ago. At first, the leaders reminded doctors with emails, faxes and posters to wash their hands. They gave out bottles of hand sanitizer to doctors arriving in the parking lot. They followed up by creating a "hygiene safety posse" to roam units, handing out coffee gift cards to those who sanitized their hands. Hand washing rates improved but not enough. And so the medical staff took a radical step. In a meeting of 20 top doctors, hospital epidemiologist Rekha Murthy handed each a sterile petri dish, via which she cultured their hands. The result: loads of bacteria. One nasty sample was photographed and turned into a screen saver, emblazoned on every Cedars-Sinai computer. That picture was worth a thousand directives as hand-hygiene rose to nearly 100 percent compliance.

The leadership of my own hospital, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, has taken an aggressive approach to hand hygiene, even calling out doctors who don't comply with stringent new rules. Our hand hygiene campaign began half a dozen years ago. At first, the leaders reminded doctors with emails, faxes and posters to wash their hands. They gave out bottles of hand sanitizer to doctors arriving in the parking lot. They followed up by creating a "hygiene safety posse" to roam units, handing out coffee gift cards to those who sanitized their hands. Hand washing rates improved but not enough. And so the medical staff took a radical step. In a meeting of 20 top doctors, hospital epidemiologist Rekha Murthy handed each a sterile petri dish, via which she cultured their hands. The result: loads of bacteria. One nasty sample was photographed and turned into a screen saver, emblazoned on every Cedars-Sinai computer. That picture was worth a thousand directives as hand-hygiene rose to nearly 100 percent compliance.

The medical center since has worked tirelessly at the task: Realizing they carry germs, old-fashioned curtains dividing patient rooms have been replaced with snap-on models with antimicrobial coatings. Janitorial crews now regularly steam-clean nonelectrical medical and office equipment; they also have swapped out mops so theirs have removable microfiber pads changed after each cleaning of a patient room.

We've also changed medical procedures to prevent common infections, such as central line blood-stream infections. Nurses now clean the skin around these catheters lines with antiseptic, not just soap and water; "hubs" that control their flow of medicine and fluids are sanitized with alcohol. These efforts have virtually eliminated infections in intensive care units.

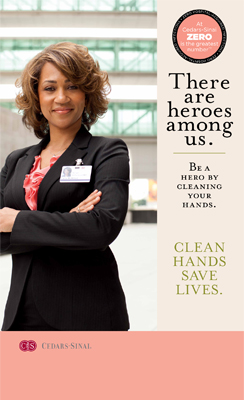

Our message gets delivered clearly and powerfully through posters on elevator doors all around the medical center. "At Cedars-Sinai," they read, "zero is the greatest number."

A National Imperative

We're not alone in this battle. Many states have made infection control a priority. California, for example, requires hospitals to report five types of hospital-acquired infections, including in the blood and at surgical sites, as well as clostridium difficile, caused by prolonged antibiotic use. And the state is training specialists to use federal data in the new National Healthcare Safety Network to help track infection rates. Scores of hospitals across the state also have organized an infection control initiative that has shown promising results.

In Michigan, home to one of the nation's most aggressive campaigns, teams in more than 100 hospital intensive care units have worked hard to share information, learn from mistakes and use checklists to reduce central line blood stream infections. The teams have focused on -- you guessed it -- hand hygiene, as well as catheter-site disinfection and removing unnecessary central lines to avoid bacterial buildup.

The results of Michigan's Keystone Project have been impressive since its 2003 launch: Hospitals cut infection rates immediately, saving more than 1,500 lives and nearly $200 million in health care costs in the program's first 18 months; in intensive care, the pneumonia rate for patients on ventilators plunged 70 percent during a 2 ½-year study.

The federal government is building on these sound results by expanding this approach to hospitals in all 50 states. The new health care reform law also provides money for states to monitor infection rates and to develop new initiatives.

Those efforts are laudable and crucial. There's also someone else who can play a critical role: It's you -- as patient or visitor. Be sure you familiarize yourself about hospital-acquired infections. If you're feeling poorly or you're ailing yourself, please don't visit hospitalized friends or relatives. When you do drop by, you will be even more welcome if you use widely available hand sanitizer. And you should feel free to ask your doctors, nurses or other health care providers to please wash their hands when they walk into the room. It's the 21st century and it may seem jarring that we all need to make such a concerted effort to practice hygiene measures that we've known about for decades. But only a relentless focus will make health care safer, better and, yes, less costly. We can't understate that by taking these small steps we will see big results in improving care and saving lives.