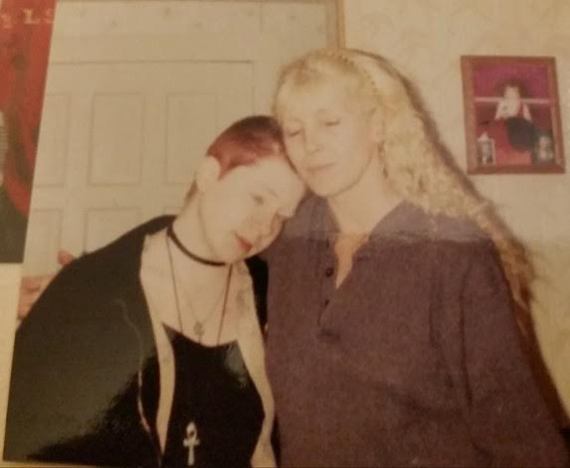

For Chavisa Woods, a New York City-based novelist, known for her distinct voice in capturing life in rural America, campaigning to get an affordable camper for her homeless mother before the onset of winter resembles a passage from one of her novels.

It's one thing when the writer can artfully expose a character's narrative and backstory, but in the case of this 32-year-old writer she worried about how others would judge her personal story. "I am a writer and have a public image and I thought people would look down on me," Ms. Woods says in an interview. "I also worried about my mother."

For this very reason, Ms. Woods has not disclosed her mother's name in the campaign, but she does provide a snapshot of what her mother's life has been like over the past several years of homelessness in a small, rural town of about 1,000 people. Ms. Woods writes on her Gofundme.com campaign page, "Over the last few years she's had multiple bouts of pneumonia and bronchitis, broken her jaw, endured a serious infection in her thumb, and was bitten by a snake while sleeping on a covered porch."

Before reaching out through social media and asking for help, Ms. Woods, who also works as a grant writer for non-profits, has tried for years to help her mother navigate an unwieldy social service system in Marion County, Illinois. "It's been a catch-22 all the time," Ms. Woods explains. "For instance, to get my mother on disability, she needs to be treated for her medical conditions, but missing appointments makes its less likely disability would be approved. In her county, the public transportation service needs at least a week's advance notice. Well, my mother doesn't have a permanent address, so she never knows where she's going to be."

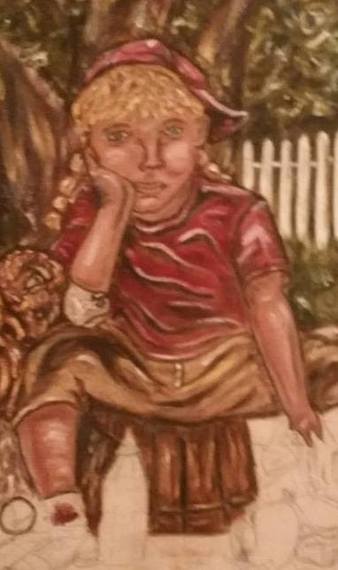

Chavisa's mother makes between $20 to $200 a month by selling her paintings and mirror etchings to local establishments and residents. Because she has nowhere to keep her art supplies at the moment, it's difficult for her to make something that will bring in money.

Having dealt with innumerable frustrations while trying to help her mother get on disability and get on the long waiting list for public housing, Ms. Woods tried to help a group in Marion County get a shelter off the ground. But it didn't work because they ran into many issues, she says, though there was community support for the shelter.

Marion County is a rural community with about 39,000 people. It's a predominantly white county, and 18 percent of the population lives below the poverty level, compared to 14 percent for the state, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. People living in rural communities have some of the highest rates of homelessness in the country, according to the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness.Nearly one in five rural counties has a poverty rate of 20 percent or more, according to the agency.

"My mother's side of the family has been poor and struggled," Ms. Woods says. "So if you are born poor and you throw any [hardship] on top of that, it makes it that much harder to get a leg up."

Making the homeless, who are already stressed and have no safety net, jump through endless hoops to possibly get some help from social services, is becoming an antiquated model to help the homeless. The Weingart Center, based in the Los Angeles-area, for instance, helps get homeless people back into regular jobs and housing to stabilize their lives, according to an article in Fast Company magazine. Then the center can start working on other chronic issues. The organization argues policymakers should be thinking of "spending on homelessness as an investment--not a donation." The center argues an investment approach is more cost-effective than donations and temporary shelters.

Ms. Woods seems to be taking the same approach. It's not a "hand-out" she is asking for but an investment in a worthwhile human being, her mother.