This is Part 2 in a two-part post. Part 1 is at this link.

Many a great idea has been deflated by a simple question: "That's nice, but who's going to pay for it?" That question hovered like a cloud over the international climate conference in Paris a week ago. Simply put, the goal of the agreement at that conference is to build a world in which we achieve and sustain universal prosperity without plummeting into a future of irreversible climate catastrophe. It's a great goal, but who is going to pay for it?

The Paris agreement does not adequately address this question, although it does reinforce the need for wealthier countries to provide technical and financial help to poor and more vulnerable countries so they can grow their economies in climate-safe ways.

That is easier said than done, however. Countries that industrialized generations ago like the U.S. and members of the European Union now face the very expensive job of repairing and upgrading their aging critical infrastructure, from roads and bridges to energy and water systems. Bridges are in danger of falling, water pipes are leaking, and electric grids are vulnerable to a wide range of risks including cyber-attack, extreme weather and inadequate maintenance.

Rapidly developing countries like China and India face their own pressing investment priorities to meet the expectations of their people and to protect themselves from the climate impacts that already are underway.

So far, developed countries including the United States have agreed to contribute at least $100 billion a year to a Green Climate Fund that will help less developed nations adapt to global warming and develop clean energy. Secretary of State John Kerry has promised $860 million for countries already damaged by global warming. But these are very small drops in a very large bucket. Estimates are that to finance the global transition to cleaner energy and to keep global warming to less than 2 degrees, nations will have to invest at least $1 trillion every year for years to come.

The good news is that much of the money problem could be resolved if the international community built on the momentum it achieved in Paris to make two fundamental changes in energy policies. The first is to stop subsidizing carbon fuels. The second is to put a price to carbon. Neither was mentioned in the Paris accord.

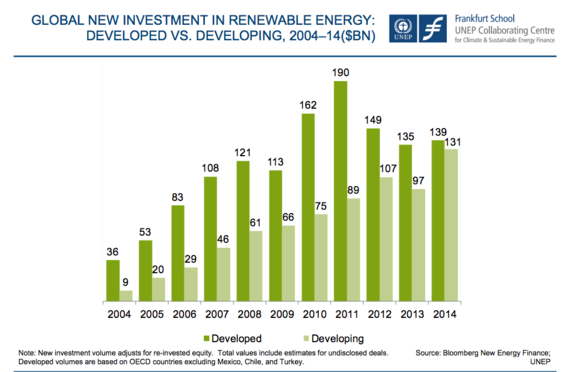

The technologies to achieve clean energy economies already exist and they are rapidly becoming competitive with fossil fuels. But global investments in renewable energy, the family of resources that offer the best hope for sustainable economic development, were only $270 billion last year, about a quarter of what's required.

Can carbon pricing and a redirection of energy subsidies answer the "how do we pay for it" question?

Fossil Energy Subsidies: Some government subsidies go to energy consumers and some to energy producers. Some are direct - tax breaks, for example - and some are indirect "post tax" subsidies, including the social and environmental costs of using fossil fuels. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), direct and indirect subsidies around the world are expected to total $5.3 trillion this year.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that 40 nations, responsible for half of global energy consumption, subsidize what their consumers pay for fossil fuels. Their subsidies for fossil energy are four times higher than for renewable energy. The IMF says that post-tax subsidies are especially large, in the range of 13% to 18% of GDP, in many emerging and developing economies, including several that want financial help to adapt to global warming.

The good news here is that some nations have either eliminated or are attempting to reform their energy subsidies. They include Brazil, France, Ghana, North Sudan, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Poland and Senegal.

The bad news is that the world's most advanced economies - the 19 countries and the European Union that compose the G20 - are not setting a good example. They have made poor progress on their commitment six years ago to phase out their subsidies.

The IMF notes that the benefits of reforming fossil energy subsidies are "potentially enormous". "Eliminating post-tax subsidies in 2015 could raise government revenue by $2.9 trillion (3.6% of global GDP), cut global CO2 emissions by more than 20% and cut premature air pollution deaths by more than half," it says.

Putting a Price on Carbon: The principal reason that climate change has become the world's biggest market failure is that the energy market's price signals are broken. Government subsidies keep energy prices artificially low. Moreover, the prices we pay at the pump and electric meter do not include the cost of damages that carbon fuels do to public health, the environment and so on.

In the United States, fiscal conservatives are militant about letting free markets and market forces make our energy choices rather than allowing government policies to "pick winners". But in Congress, the same fiscal conservatives are silent about government subsidies for coal, oil and gas.

There is some good news here, too, however. The New Energy Economy (NEE), a project commissioned in 2013 by the governments of seven countries, reports that 40 nations and more than 20 cities, states and regions have adopted or are planning to institute carbon pricing. That is triple the number of a decade ago. In the United States, they include California and nine states engaged in carbon trading in our northeast and west central regions. In addition, more than 1,000 major companies and investors around the world have endorsed carbon pricing, including British Petroleum and Royal Dutch Shell, and about 450 companies use their own internal carbon pricing to guide investment decisions.

The most common argument against carbon pricing is that it would kill jobs and cripple the economy, but actual experience shows this is not necessarily the case. One example is found in the nine U.S. states whose carbon trading I cited above. Between 2009 and 2013, their economies reportedly grew more than 9% compared to 8.8% in the other 41 states, while their combined carbon emissions dropped 14%. The net economic benefit to the region's economy was $1.3 billion.

What's Next? The 195 countries that endorsed the Paris climate agreement promised to keep "ratcheting up" their efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They will meet again at the end of 2016. Despite the fact that carbon pricing and energy subsidy reform are not mentioned in the Paris pact, the United Nations should ask them to show up ready to report what they are doing about these two issues. In fact, it would make sense to amend the Paris agreement next year to say that no nation will qualify for financial help under the pact until it has implemented these two policies.

There are no more promising ways to achieve energy and environmental security while avoiding catastrophic climate disruption. As I wrote in Part 1, the United States can lead the way if President Obama uses his bully pulpit to make carbon pricing and the phase-out of fossil energy subsidies decisive campaign issues in next November's elections.