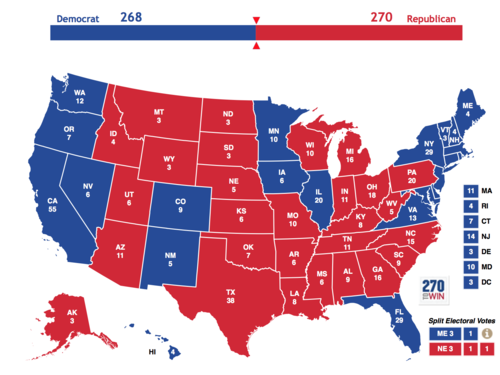

By now, there are no secrets: As incredible it is that Donald Trump is the presumptive Republican nominee, his prospects for winning in November are slim. Indeed, many map-crunchers have pointed out that, in order for Trump to win the White House, he is going to need to flip some pretty strong blue states. Here is one possible path for Trump:

For sure, this looks tough. A Republican candidate has not won Michigan nor Pennsylvania since 1988, nor Wisconsin since 1984. But there is growing evidence that we are in the midst of a major party realignment, just the kind that could produce the result shown above. If Trump can exploit this moment in history in his favor, coupled with a few miscalculations by Hillary Clinton, he could indeed become President #45.

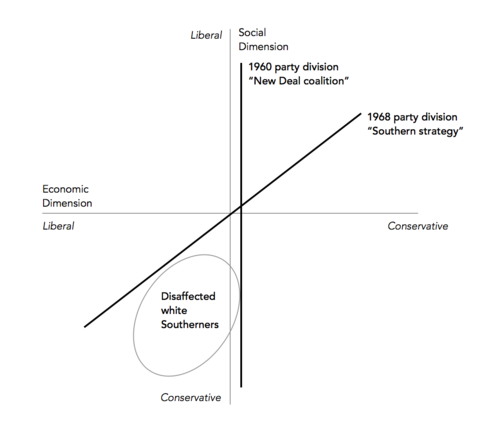

In a 2003 paper published in American Political Science Review, Gary Miller and Norman Schofield argued that our traditional beliefs about party alignments are misguided. Political parties, they argue, do not exist on a one dimensional plane--with conservatives on the right and liberals on the left--but on a two-dimensional plane including both an economic dimension and a social dimension.

Within this construct, political parties are held together along one dimension--social or economic--and over time disagreements along the other dimension begin to form. In turn, political candidates, driven by a need to grow their own coalitions, are able pick off disenfranchised voters from the other side, realigning the parties. We saw this most prominently with Richard Nixon's Southern Strategy, when Republicans were able to steal away disaffected white southerners who began to disagree with the Democratic party on social issues. On Miller and Schofield's diagram, the strategy looked something like this:

Until now, the Southern Strategy has endured--the parties, more or less, have been held together on social issues. That is why, for example, that the Republican party has consistently performed well with lower-middle class social conservatives even as the party has supported economic policies favoring the wealthiest Americans, and why "socially liberal, fiscal conservatives" in the North have continued to support the Democratic party.

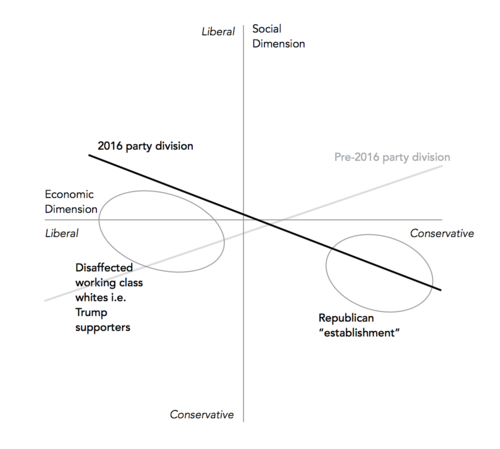

But there is evidence that these coalitions are starting to break. Trump, the Republican candidate, has succeeded in large part because of his opposition to free trade and his economic isolationism, traditionally more liberal positions. Clinton, on the other hand, along with her husband and President Obama, has championed free trade agreements and embraced globalization, positions we typically associate with Republicans. Moreover, Trump has invoked the New Deal as plan he wants to emulate, and has proposed a public works plan far larger than Clitnon's. Finally, we have even seen large corporations--once the bread and butter of the Republican party--increasingly align themselves with the Democratic Party, most recently with the debacle in North Carolina.

This shift away from social cohesion to economic cohesion explains why Trump has succeeded despite his wishy-washy record on abortion and gay rights, typically believed to be make-or-break issues in the Republican party. It also explains why disgust with "The Establishment" has been so prominent in this campaign--it is Republican voters revolting against a party that has not done enough representing their interests on the economic side.

On Miller and Schofield's model, then, we likely find ourselves somewhere around here:

This shift would explain the current split we are seeing within the Republican establishment. Most notably, House Speaker Paul Ryan said he is not yet be willing to support Trump. But down the line, there are signs the cohesiveness of the Republican party is beginning to fray. Senator John McCain said he is endorsing Trump, while his counterpart, Jeff Flake, said otherwise; both presidents Bush have said they will not attend the convention; and 2012 GOP nominee Mitt Romney has been one of the architects of the "Never Trump" movement. Moreover, GOP bigwigs Robert Gates and David Petraeus have even voiced support for Clinton, and her campaign is reportedly beginning to reach out to former GOP voters (on the model, those voters are found between the pre-2016 and the 2016 party division line on the right side).

So how does this affect the 2016 race? It just so happens that the disaffected working-class whites that are now likely to become part of the Republican party are heavily concentrated in states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ohio -- states that are crucial to Trump's success in the general election. By exploiting this realignment of the parties -- by fervently talking about the loss of American manufacturing jobs and attacking free trade deals -- Trump may be able to peel of enough voters to pull of victories in those states (you may call this the "Northern Strategy"). Wheras Nixon was able to succeed by appealing to working-class Southerners who increasingly found themselves disagreeing with the Democratic party on social issues, Trump would succeed by appealing to working-class Northerners who increasingly find themsevles disagreeing with the Democratic party on economic issues.

There's reason to believe this is possible. Trump performed extraordinarily well in those Northern states in the primaries (besides Ohio, John Kasich's home state), and Clinton was exposed as vulnerable there. Additionally, Trump's success in open primaries -- where a voter can pick a candidate no matter which party she is registered for -- suggests voters traditionally believed to be in the Democrats' camp could be in play.

For Clinton, there will be pressure to try and peel away voters on both sides of the model. You could argue that some of those disaffected white working-class voters, many of whom went for Bernie Sanders, are in play for Clinton, which could induce a strategy that involves tapping Elizabeth Warren (also an opponent of free trade deals) as Clinton's running-mate. But such a move could turn off voters on the other side of the model--former GOP voters--that could also be critical to Clinton's success. In other words, Clinton may have to choose one side to work with--going after both kinds of voters could cancel each other out, possibly starving voter turnout or, worse, sending voters to Trump.

Coupled together--an effective Northern Strategy from Trump and a greedy misstep by Clinton--it is not hard to imagine Trump walking away victorious in November. The parties are indeed beginning to move, and the next president may be determined by who better understands that reality.