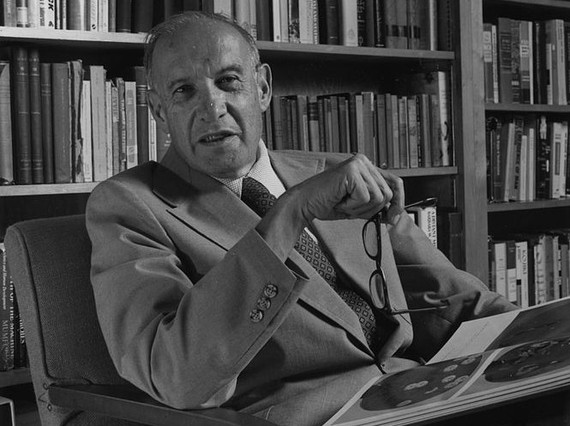

"There is a difference between doing the next thing right, and doing the next right thing."

-- Peter F. Drucker

Online quizzes have suddenly become a "cheap -- if vexing -- form of modern self-analysis," according to The Wall Street Journal. In a recent 24-hour period, 97 million people took a quiz to determine which Disney Princess "matched" their personality; 41 million people tried to determine which state is best suited for their personal traits; and 20 million sought to find out which city they should live in. As this tsunami of lightweight online quizzes engulfs the world, I think you would agree that it behooves us to try and take one that truly matters.

Let's take a quiz that pinpoints how human the companies for which we work are.

It's far from a trivial questionnaire, but rather a meaningful form of organizational analysis that gets to the very core of whether or not our companies and their workers will thrive in the new conditions of the 21st century. Taking the "How Human is Your Company?" quiz has a heck of a lot more at stake than figuring out if we're more like Cinderella, Snow White or Mulan. That's because assessing our company's humanity also tells us about our company's capacity for performance.

Yes, I said "performance."

I'll get to that connection in a moment, but first let's get into corporate humanity. In the past several years, more and more companies have been asserting their humanity: Ally Bank speaks human; Chevron is the human energy company; Cisco is the human network; Dow is the human element; JetBlue says they "air on the side of humanity"; Samsung is designed for humans, and so on. The trend is so prevalent and so consequential that Ad Age has even pronounced "human" the newest marketing buzzword. What's more, a recent MarketingWeek article reports on a study that describes a "societal shift in relationships that requires brands to behave like humans in order to connect with consumers and build trust." (By the way, as more and more companies assert their current humanity it raises a question about their previous behavior - did these companies used to be inhuman, monstrous, or were they just inconsiderate?)

Sure, these proclamations can be casually dismissed as marketing campaigns, but keep in mind that marketers are supremely adept at understanding the current context in which their companies operate and pinpointing society's social (read: human) nerve. We should celebrate the fact that some marketers have nudged their companies into a promise of humanity from which they cannot retreat. (Some of these efforts have even catalyzed companies into operating in a more human manner, as we have witnessed before. But we can't stop there. The work of humanizing organizations must spread beyond the marketing department and permeate the whole organization.)

What does it mean for a company to be human? For starters, it means we want our companies to embody the best - not the worst - human capacities and qualities. Peter Drucker's distinction between "doing the next thing right, and doing the next right thing" nails a profound difference between humans and machines. Getting the "next thing right" is what we program software and robots to do by giving them a script of what they can or cannot do. In the same vein, we have scaled a management model where we "programmed" - and still do in some ways -- employees to implement or execute a strategy set by top management.

Doing the "next right thing," however, is a uniquely human endeavor. It requires pausing -- and then using that pause to think beyond what we can or cannot do to grapple with what we should or should not do. This act requires a moral conscience -- one of the main differentiators between humans and other life-forms - which enables us to be thoughtfully conscious of all the stakeholders affected by our behaviors. While machines may beat humans in how fast or how much they can process or produce, our humanity is most manifest in how we do things: how we think, imagine, create, collaborate, share information and relate to others.

It is one thing to develop and manifest one's humanity, but quite another to develop and scale it throughout an entire workforce. The upcoming Global Drucker Forum this November, where I am speaking, will address the responsibility of leaders to transform their companies into more human organizations so as to guide them onto a path of sustainable prosperity. The Forum brings a sharp focus to this critical issue, and in doing so highlights and amplifies the enduring relevance of Drucker's teachings.

Quality was once job No. 1, with companies doing the hard work of systematizing quality (and let me remind you that before it was job No. 1, it was marketed as such). Now, in the 21st century, humanity is becoming job No. 1 because of how easily and inexpensively we can peer into individuals' character and into the inner workings of companies. Because we can see how companies truly behave, we want to see more of how they behave: What does your company stand for? The stakes involved in answering that question are high. As Drucker wisely warned, "There has to be something 'this organization stands for,' or else it degenerates into disorganization, confusion and paralysis." He went on to draw an analogy between companies and humans, by pointing out a company "needs a commitment to values and their constant reaffirmation, as a human body needs vitamins and minerals."

We can now ask, and answer, that core question about corporate character. The answers -- just like the existence of product defects during the quality revolution of the last century -- are the key indicators of which companies will perform and thrive, and which ones will not survive.

It turns out that the more human your organization is, the better it performs. The most human companies (i.e. self-governing) significantly outperform less human companies (rules-based or "informed acquiescence" companies, as well as autocratic or "blind obedience" companies) in areas of financial performance, innovation and related measures of success, according to research developed by my company LRN and independently conducted by the Boston Research Group. The research shows that the most human companies are 10 times more likely to outperform less human companies in the short-term, and more than 20 times more likely to outperform them in the long-term. The sum of all behaviors in a company -- and the degree to which those behaviors coincide with, or contradict, its shared values -- form a company's corporate character.

Humanity not only serves as a performance propellant, it also functions as a bulwark. The most human companies are also far less likely to foster inappropriate behavior, including the type that leads to regulatory compliance problems and enforcement actions. That's important right now, given the risk of corruption that our ever-more global enterprises confront. Our organizations operate in a world where more than one in four global citizens has paid a bribe in the past 12 months, according to Transparency International. As I've been asserting for years, how an organization behaves represents the final frontier of competitive advantage.

The fact is that all companies, regardless of their character, are asking their people for much more human contributions. Rather than executing checklists (never mind online quizzes), we want our employees to exercise judgment. Rather than deferring to marketing or PR, we want our people to behave as chief marketing officers while conveying the company's key messages in their own words, through their own networks. Rather than merely providing products and services, we also want our people to forge deep experiences and relationships that will sustain through ups and downs.

The question is whether companies possess a corporate character (the sum of all employees' behaviors) that is consonant and enables, or is dissonant and fights, with these desired human behaviors. How human are our companies currently? Not human enough, according to the early results of LRN's ongoing global surveying of corporate characters: only 3 percent of companies truly qualify as sufficiently human. Changing our corporate characters is difficult but necessary work. To get started, take the quiz.

You won't find out who you'd be as a princess or whether you're more suited for Boston or Boca Raton. You will find out what your company's made of, how it stacks up against the competition and how well it's suited for principled performance -- the only performance that counts in the 21st century.